FORT SILL, Oklahoma July 12, 2021 -- Stationed in the 22nd Ordnance Company, in Munich, West Germany, in the chaotic days following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the crash of a decommissioned atomic cannon on the autobahn tested a new Army second lieutenant who was put in charge of recovery efforts.

Now, nearly 58 years later and living in Fox Lake, Illinois, 81-year-old Paul Jakstas was removing paperwork and other items he didn’t believe his family would be wanting when he came upon his notes from that moment in Army history. Being the village historian, he said he dealt with things like this and began checking the internet to see if there was someone or some agency that might appreciate what he’d kept.

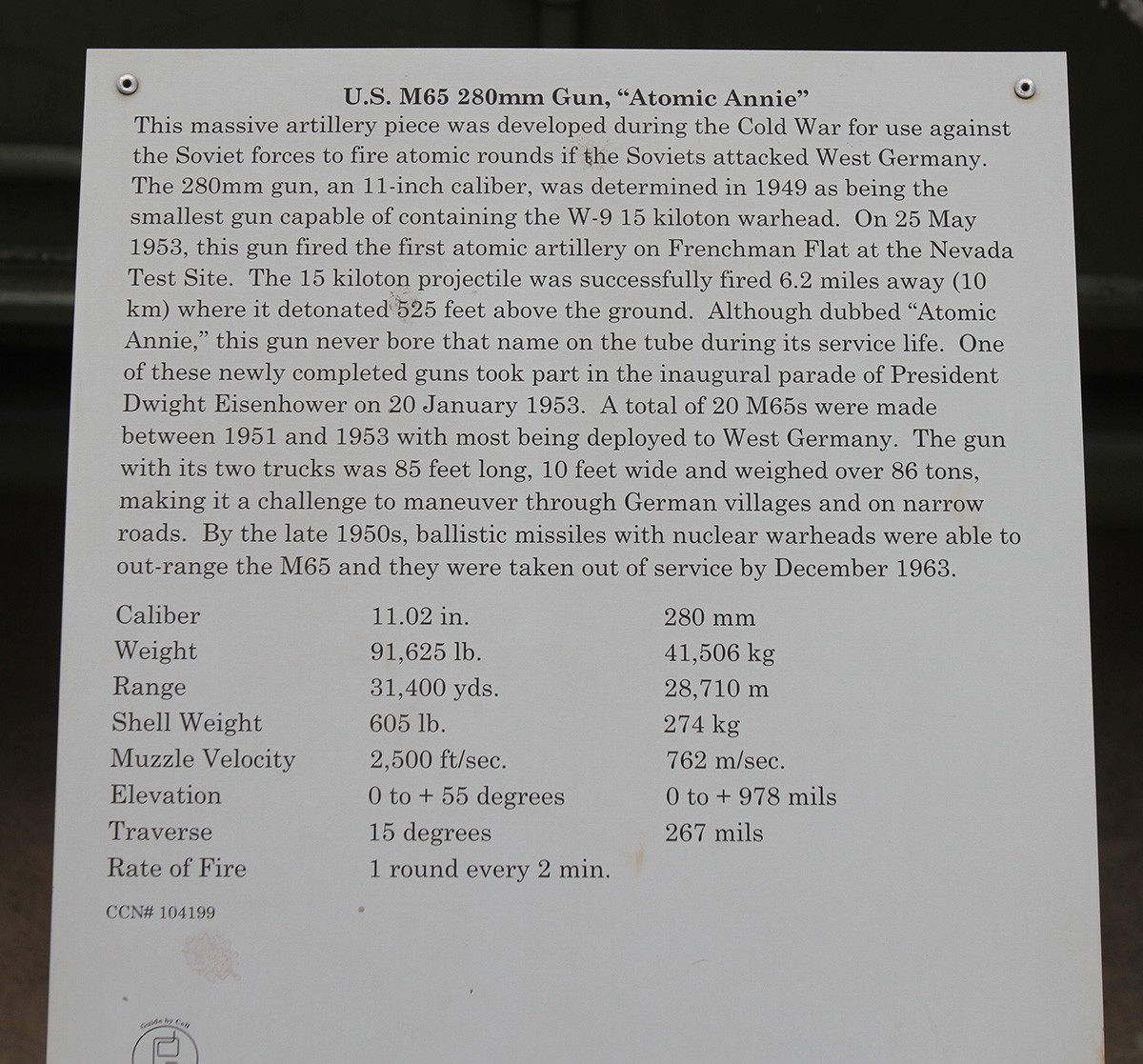

That’s when he came upon Fort Sill and realized that Atomic Annie resides here in Artillery Park.

Germany 1963

Jakstas was just beginning his brief two years of active-duty service when the accident occurred. As for why a “green” second lieutenant was given a task that drew a lot of attention, it followed his first significant contribution to his unit.

As a Service, Supply, and Recovery officer, Jakstas was assigned to lead the repair work of a substantial number of military vehicles in preparation for Operation Big Lift. The exercise moved an Army division from the United States to support its allies in Germany and show Eastern Bloc countries American quick response capabilities.

He said hundreds of vehicles and tanks, many of them cannibalized for spare parts, were stored in the woods nearby.

“The assignment was meant for a more experienced officer than a new second lieutenant,” said Jakstas. “They wanted someone who could run four platoons of personnel.”

Recalling the time with a measure of pride, he said he wasn’t quite as green as they may have thought. He graduated from what he called a well-run high school military academy that prepared him for Army life.

‘I was comfortable and loved the duty,” said Jakstas, who said the special duty assignment lasted several months.

But then everything changed and with that change U.S. service members around the world faced a lot of uncertainty.

Nov. 22, 1963, Jakstas played in a platoon basketball game at a neighboring post when the game stopped with word of Kennedy’s death. Although his unit went on alert status, no immediate threat materialized.

Instead, early Nov. 23, Jakstas’ unit received an emergency call about the accident that involved vehicles carrying an artillery piece. Seven Soldiers were injured with two trapped in the wreck. Those two were later removed, and all survived.

Despite serving in his position less than four months, Jakstas earned the trust of his company and battalion commander who selected him for the recovery operation of the atomic cannon.

“As the designated recovery officer, I mobilized some wheels/tracks and headed north on the autobahn,” he said.

Arriving on scene, he found the 84-foot long gun with its fore and aft attached trucks askew blocking traffic. While a warrant officer handled the physical recovery matters, Jakstas managed the public affairs details. This included updating angry West German officials upset about the closed thoroughfare, media queries, and high ranking U.S. Army officers checking on progress of the recovery.

With the world in turmoil over Kennedy’s assassination, Jakstas said media interest was minimal. The wrecked vehicles were removed from the accident scene by Nov. 25 and the autobahn soon reopened.

His duties were then extended as he became the survey officer who conducted the official accident investigation. Jakstas’ report concluded the lack of proper maintenance and spare parts resulted in steering and braking troubles. A broken communications system that prevented the two drivers to coordinate their movements contributed to the accident.

Although he liked Army life and considered continuing his military career, Jakstas left active duty in 1965 to manage a marina back home with his brother. Later, he worked for corporations in project and personnel management for 37 years. He also drew on his Army leadership training giving seminars to raise up leaders.

Having long since turned in all official documents, Jakstas kept his notes and photos of the accident, which mostly went untouched until recently.

Field artillery perspective

Dr. John Grenier, Field Artillery Branch and FA School historian spoke of the value of having these documents. He called the notes “primary source documents,” which means they were made by a person who was at the scene when it occurred.

“We use those documents to build our interpretations of the past. The further away we get from when an event occurred, the more clouded and confused they become. Having an eye witness account compared to a narrative written 20 years after the fact allows us to analyze and explain why this happened,” he said.

Understanding the why an event occurred can then bridge to asking to the right questions to further clarify and learn lessons from the vent.

Grenier went on to say the notes should provide insight to a world that was different than what we live in today.

“It was a world in which the Cold War was the dominant military threat of the Army and other U.S. military branches,” he said.

Although the U.S. was involved in Vietnam that war wouldn’t escalate for another two years. So, the Army was focused on readiness to counter large-scale combat operations in central Europe brought on by the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact nations, he said.

When the Cold War ended in 1989, that threat dissolved, but Grenier said, “there’s a lot of similarities between the early 1960s and what I believe we are going to see in the early 2020s.”

Social Sharing