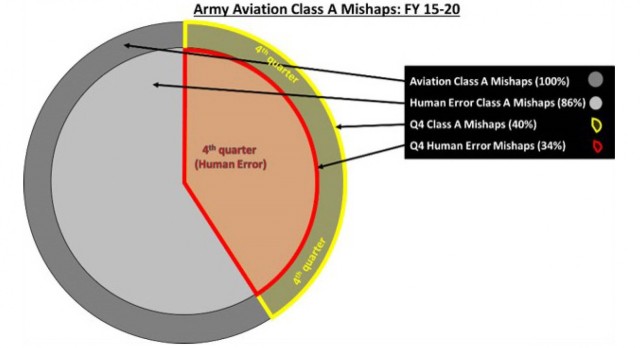

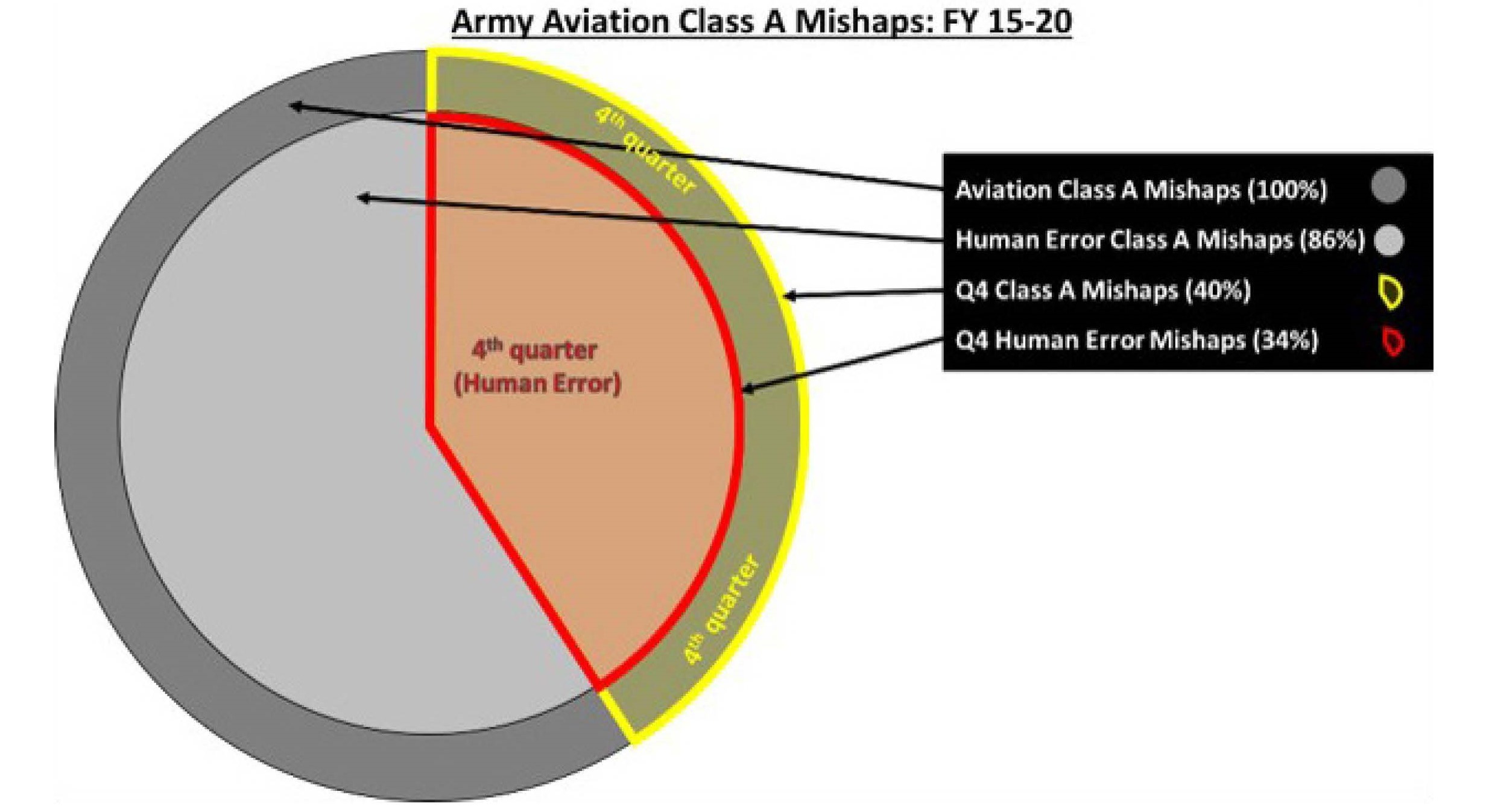

Over the last several years, Class A mishaps have spiked in the fourth quarter, accounting for nearly 40% of all accidents each fiscal year (U.S. Army Combat Readiness Center [USACRC], 2020). With human error accounting for 86% of all Army Aviation mishaps (USACRC, 2020), the fourth quarter has become a focal point for accident avoidance campaigns, as these types of accidents constitute approximately one-third of all Class A mishaps for the year. Therefore, despite routinely being one of the safest military aviation services, Army Aviation must take steps to reduce mishaps related to human error, especially during the fourth quarter.

While many factors are contributing to the phenomenon known as the “fourth-quarter spike” (Hilmes, 2020), extensive summertime personnel turnover undoubtedly increases risk in our formations. Personnel moves during the summer can cause a lack of familiarity between crewmembers, mission briefing officers (MBOs), and commanders serving as final mission approval authorities (FMAAs). We must all do our part to prevent the fourth-quarter spike by bringing a disciplined approach to every aviation mission we conduct. In particular, understanding and enforcing the proper use of the emergency response method (ERM) will help save lives.

Aircraft emergencies, whether real or simulated, oftentimes place crews in challenging situations where they must respond to degraded systems or performance. In these instances, having a thorough understanding of the emergency response method, and when and how to incorporate the flight reference cards, is a force multiplier. MBOs and FMAAs should ensure their personnel fully understand this process each time they head out for a mission. Likewise, crews should monitor each other to ensure all crewmembers stay in step with one-another during any application of the ERM.

In recent unit visits, the directorate of evaluation and standardization (DES) has identified a lack of understanding of how to apply the ERM outside of scripted scenarios, such as within the traffic pattern. The ERM is intended to prioritize crew actions to focus on the most important aspects of emergency response – flying the aircraft first and foremost – and provide crews with the most options to survive the situation. Given the redundant nature of most systems on our modern aircraft, this typically means FADEC-F slows crews down prior to executing underlined or non-underlined emergency procedure (EP) steps. The ERM also provides a cadence for all crewmembers to monitor and enforce throughout the event. With these newly developed procedures, it is important that crewmembers understand how to apply these new concepts as a crew.

Fly the Aircraft: RAASH

If a crew receives an indication of an engine malfunction and low rotor RPM, what should their initial considerations be? People quickly recite “fly the aircraft,” but what does that really mean? The reason the Fly portion of FADEC-F lists rotor speed, attitude, altitude, speed and heading (commonly referred to as RAASH) is that the crew must reference and control these items immediately to maintain the safest aircraft profile. These critical considerations are listed in a top-to-bottom priority; however, crews are reminded that a major emphasis of the ERM is to respond to emergencies in context with the situation, rather than by simply executing rote-memorized steps.

Alert the Crew to the Problem

While aircraft control is the primary concern, it is important to near simultaneously alert the entire crew to the emergency condition. In addition to audio signals or warning/ caution/advisory lights, other indicators may include abnormal vibrations, sounds, and smells, which can be detected by any crewmember. It is imperative that whoever recognizes the emergency alert the entire crew to the situation to build shared understanding.

Diagnose the Malfunction

Accurate fault diagnosis is critical to any emergency response; it enables crews to rapidly proceed to execute EP steps, confident they are applying the correct procedures the first time. During recent unit engagements, DES has observed several crewmembers speed through the Diagnose step in favor of immediately executing the EP. Crews are reminded that after completing Fly, they will most likely have sufficient time to thoroughly diagnose the situation and ensure they are responding to the correct emergency. The FRCs provide a tremendous resource for crewmembers to help confirm their diagnosis prior to executing EP steps.

Execute the Emergency Procedure

Crews must understand that adjusting flight controls to achieve the safest possible profile during Fly (RAASH) is not the same as deliberately executing EP steps following Diagnose. While there may be instances where adjusting a flight control to Fly the Aircraft overlaps with an EP step, the crew should not confuse themselves by thinking they have now completed the EP. Rather, crews should think about RAASH as actions that will provide the crew as much time as possible to respond to the situation. The ERM and FRCs work together to prioritize crew actions and streamline information flow at the correct moment. Combined, these components assist the crew to establish the safest flight profile and then coordinate the remainder of their actions to survive the emergency.

Crews must also be prepared for the most severe emergencies, such as a dual engine failure. Despite the very low likelihood of occurrence, the risk to aircrew and aircraft in these catastrophic situations is exceptional; we must be ready to react instantly. After placing the aircraft in the safest profile (RAASH) we must rapidly diagnose and execute underlined EP steps from memory. There may not be time for the crew to reference the FRCs during these time-critical emergencies, so crews must be ready to react instinctively without additional references. However, the vast majority of emergencies Army aircrews respond to permit us to respond much more methodically. Out of the 142 Class A mishaps involving AH-64, CH-47, or UH-60 aircraft since fiscal year 2010, only 10 (or 7%) involved a catastrophic component failure with minimal time for the crew to react (USACRC, 2021).

Communicate a Plan: Involve the Entire Crew

For aircraft with nonrated crewmembers (NRCM) on board, they should be included in the crew brief with specific priorities and duties throughout the flight. The NRCM may be in a better position to cross- monitor crew performance and alert them to any unannounced or unexpected actions. On aircraft with two NRCMs on board, one technique includes having one refer to the FRCs while the other monitors the crew and searches for a suitable landing area.

Fly the Aircraft

Crews must remain vigilant and continue to fly the aircraft throughout the emergency until reaching a logical conclusion. This could mean the crew continues the mission, safely arrives at an airfield, or performs a forced landing. In all instances, the crew must always fly the aircraft.

Conclusion

With most fourth-quarter accidents occurring as a result of human error, we must take steps to make our force safer. As MBOs and FMAAs, we must ensure our crews are prepared to respond to emergencies by asking direct questions to ensure understanding. As crewmembers, we must maintain discipline in the cockpit by holding each other accountable for the steps of FADEC-F throughout any real or simulated emergency. When we conduct crew debriefs following these events, we must be honest with each other about what we did well but also how we could have applied FADEC-F better as well. Most importantly, integrating NRCMs into ERM training and execution is paramount to a fully informed crew. Assigning duties to NRCMs during crew briefs allows the entire crew to coordinate action sequence and timing to ensure the actions of one crewmember mesh with the actions of others to successfully execute the emergency.

We all play a part to prevent the fourth-quarter spike. We must train for emergencies using realistic scenarios and hold ourselves to the standard as a crew when conducting the ERM. By embracing the ERM – as aircrews, MBOs, and FMAAs, we will create a more proficient, better standardized, and more survivable force.

Social Sharing