FORT SILL, Oklahoma (April 15, 2021) -- When she was 10-month-old during World War II, Marija Fine was taken from her family by Nazi soldiers and placed in a Latvian orphanage. After the war, as an orphan she would go on to the United States and get adopted by an American family. Later in life she found out what had happened to her birth family.

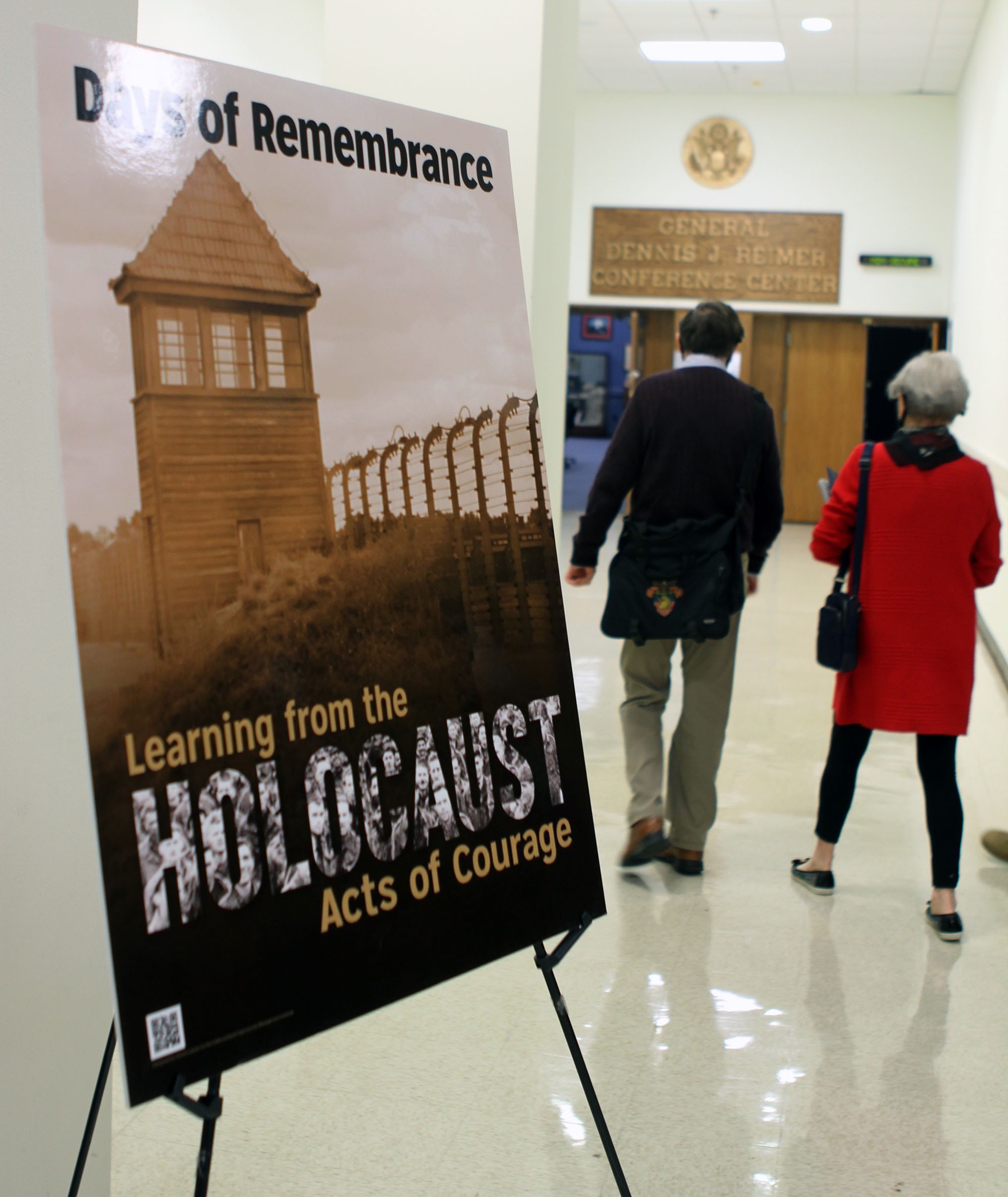

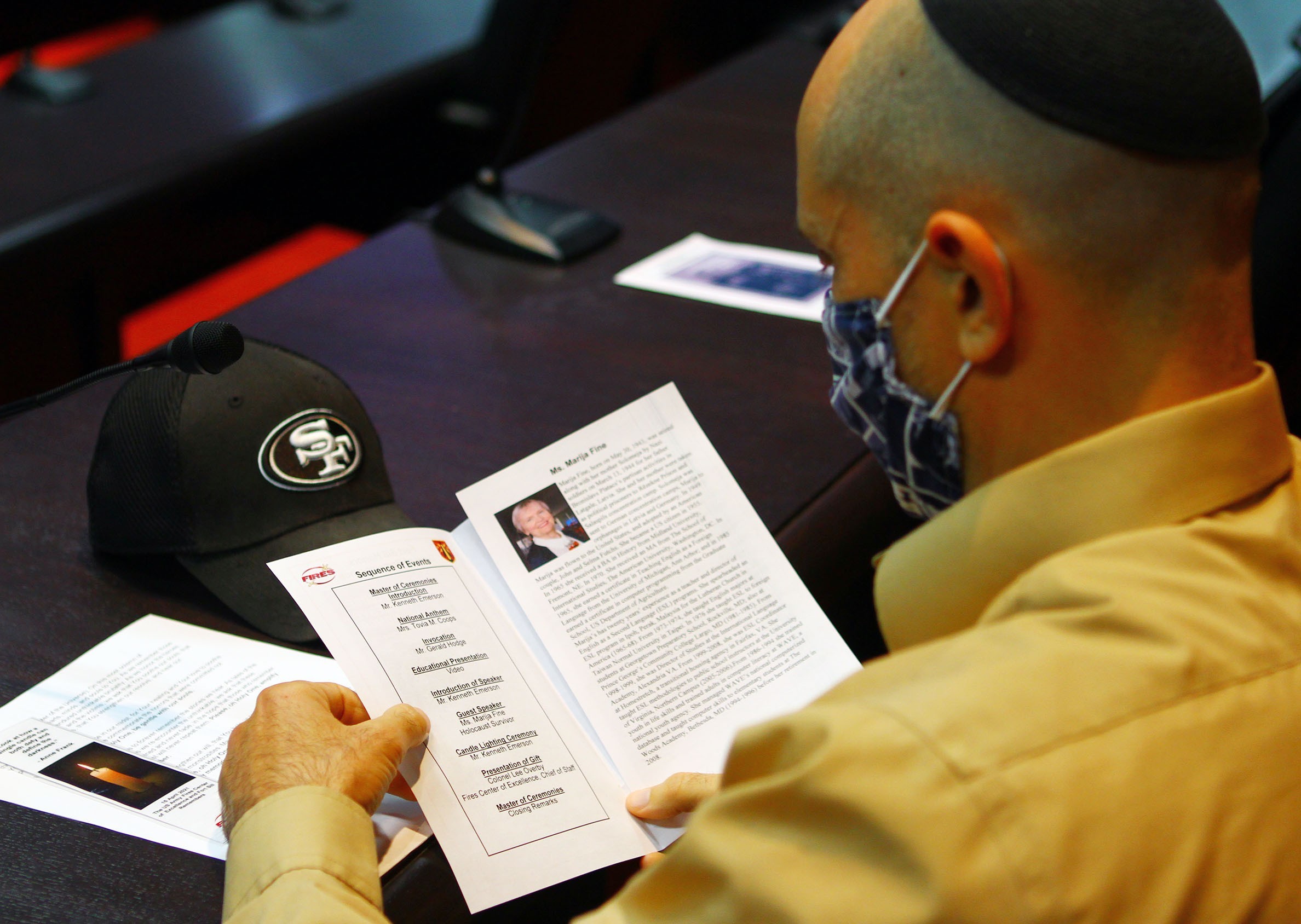

Fine, now 77, presented her story to the Fort Sill community April 15, during the Days of Remembrance observance at Snow Hall.

The annual commemoration was co-sponsored by the Installation Equal Opportunity Office and the Fires Center of Excellence, and hosted by Maj. Gen. Ken Kamper, FCoE and Fort Sill commanding general. This year’s theme is: “Acknowledge, Preserve, Honor.”

“Knowing who you are, your roots, is so important even if they’re tragic,” Fine said.

Fine was born May 30, 1943, in Latvia, a country on the eastern side of the Baltic Sea, the country was a prize fought over by the Soviet and German armies for open shipping ports.

Fine’s family, the Platicis, were Lutheran farmers where the struggle to survive meant siding with either or the two opposing forces, or switching sides depending on who they thought would win or offer the most security.

Fine said her family opted for the Soviet Union, not because they considered themselves as communists, but because they believed Adolph Hitler could not win the war.

But, when German forces regained control of their town, someone, probably within the family, reported the Platicis as Soviet sympathizers. Soldiers arrested Fine, her mother, grandmother, and great uncle. Fine’s father and uncle evaded capture, but her grandfather was murdered by the Germans for supporting the Soviet cause.

Shortly thereafter, Fine was separated from her family and that was the last she saw of her relatives for about 70 years.

How an infant survived such a tumultuous time is a wonder, but Fine believes her blonde hair and blue eyes kept her from arrest and imprisonment.

She said the Nazi party envisioned a new Germany whose current population was woefully inadequate to meet its grand intentions. And so, German soldiers kidnapped blonde-haired, blue-eyed children no older than age 10 from surrounding countries and sent them to German orphanages.

Fine said the Nazis stole about 250,000 young children who fit this ideal.

“I was astonished to learn about lebensborn, and I believe that was the reason because other people in my family were ignored or sent to camps as enslaved labor,” she said.

For the remainder of the war kidnapped children were shuttled around Latvia, Poland, and finally Germany until it surrendered.

But, even as one war ended, another – the Cold War – began and with it Fine’s survival remained uncertain as the United Nations, the Soviet Union, and her Latvian caretakers contended for where the children would be settled. She said the Americans and British countered the idea of returning the children to a totalitarian state even if they were born there.

With the passage of the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, Fine and about 200 other children immigrated to the United States, parted of an estimated 400,000 Europeans allowed entry into America.

Eventually she was selected for adoption into the family of Rev. John and Selma Futchs, a Lutheran pastor in Boulder, Colorado.

“I loved Colorado. That first Christmas there was snow on the ground, and the people of the church were wonderful in how they welcomed me, this refugee from the war in Europe, and gave me all sorts of clothes and had parties for me.”

Speaking of her new mother, Fine said it was love at first sight, though as she matured she drew closer to her father. But early on, the couple worked hard to help her assimilate into her new life.

“They really made an effort my first summer to teach me phonics, which led me to be able to spell and to speak the English language,” said Fine. “Within three months I was in the fast-reading group in the first grade.”

She didn’t live in Boulder long. He father’s clergyman duties took them to Denver. When he left the church, the family would move to El Paso, Texas, and then Nebraska, Fine said.

She credited her adoptive parents for encouraging her to seek out her birth family.

“I really honor my parents for that, starting first with keeping my name,” though they altered it slightly changing the J to a Y to avoid confusion in pronunciation. “They told me, ‘Your father and mother lost you, but they were good people, and we want you to be proud of your Latvian heritage.”

She didn’t know much even into her college years of her Latvian heritage adding that early searches revealed fabricated stories that reflected the Cold War era.

These tended toward, “Your mother died in childbirth, but you father continued to fight the communists,” she said.

Immediately after high school, she had an opportunity to teach English in Malaysia, and did so. She said a bachelor’s degree in history from Midland University in Nebraska in 1965, prepared her for an earnest search to find her birth family.

Fine went on to earn a master’s degree from The School of International Studies, The American University in Washington, D.C.

In 2014, she decided to go back to Latvia, but before leaving, she went to the Latvian Embassy in Washington, D.C. and asked if they might help her find any information about her parents. Despite only being able to provide her parents’ last name and the city of Riga, where she was kept in an orphanage, in two days she got a response with the full names of her parents and their birth dates.

She then turned to a researcher from the American Latvian Association who through several calls and conversations found Fine’s Aunt Leonora, her father’s sole surviving sister.

“To have that personal link back to someone who knew me as a newborn child was very wonderful,” she said.

Although the two women didn’t share a common language, they communicated through Leonora’s son. Fine learned of her father’s many attempts to locate her which culminated with Red Cross searches that included several countries.

Ultimately, he learned his daughter was alive, but due to the Cold War, no specific information on Fine’s whereabouts was shared.

“I learned that my parents loved me and that we all had a love for singing and playing musical instruments,” said Fine.

If she had a choice, would Fine have selected being brought up in Latvia or America?

“I was blessed,” she said. “I just landed in a wonderful place with the people who adopted me. The only regret I have is that I actually never got to meet my (birth) parents.”

Her mother Solomeja Platicis died in 1988, the same year her American mother Selma died.

“They had very similar names … so I feel the two mothers came together,” Fine said.

Her father Bronislavs died in 1991.

Fine returned to Latvia in 2014 and saw where she grew up, her church, and an orphanage she lived in. She also returned to Boulder a couple years ago and saw the house she had lived in for about three years. “It hadn’t changed at all except they were breaking it down into two apartments.”

She wrote a book of her search for her family called “Wide Eyes” that was published in 2016 and subsequently published in Latvia.

Through the book many family members learned more about the war years and various relatives' involvement. The book also includes a chapter of what Fine believes might have happened if her parents had found her in America, she said.

“The book represented the skills I acquired through my education to tell the story I didn’t know for 70 some years. I was so glad I could tell my family’s story because they weren’t educated. They were a farming family and didn’t know a lot about what went on,” she said.

Today, Fine, a retired English teacher, lives in Washington, D.C., very close to Fort McNair.

Social Sharing