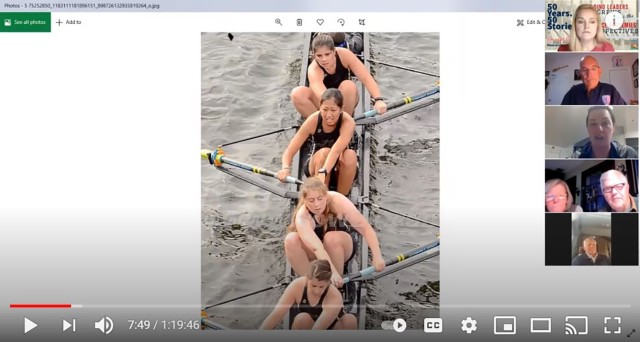

Pride. Respect. Commitment. Those three words are compelling to all 84 male and female members of the Army West Point Crew team who exhaust their mental and physical energies day in and day out to compete for four years in collegiate rowing. The Army West Point Crew team was founded in 1986, and ever since then it’s been aggressively racing during the fall and spring seasons on America’s waterways.

Since last spring, however, the competition well dried up due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the team has been practicing vigorously recently to get back into race mode as it competed against the Coast Guard Academy Saturday. Both the men and women raced three times at three different levels, and Army won four of the six races.

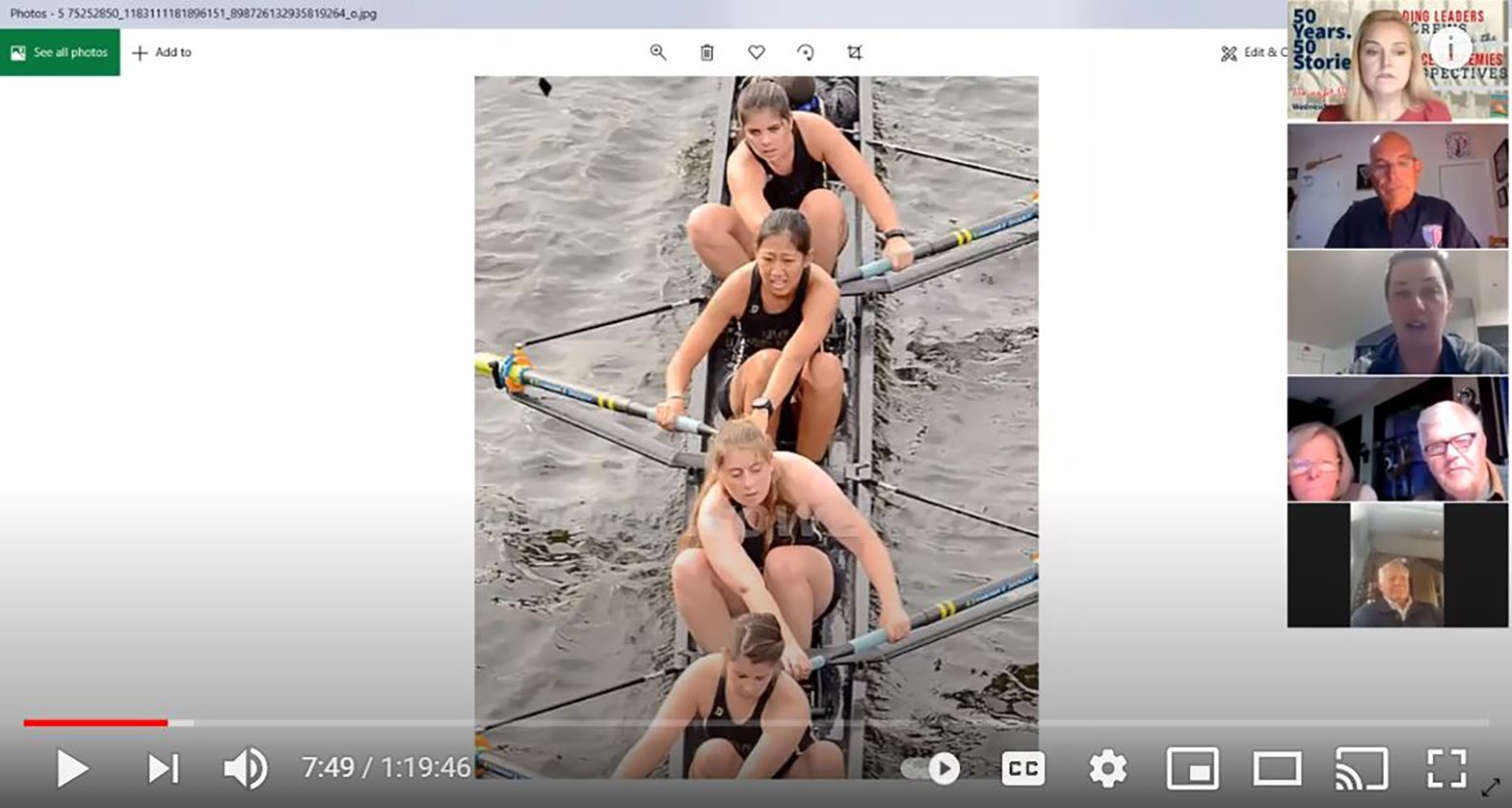

Prior to the weekend race, more than a couple weeks ago on March 24, coaches and members of the team, past and present, were part of a discussion sharing their crew experiences with the rowing community during a “Story Hour” hosted virtually on Zoom by the Head of Schuylkill Regatta’s Executive Director, Jennifer Wesson.

This past fall season would have been HOSR of Philadelphia’s 50th anniversary race, which is an event the Army West Point Crew team participates in yearly, however, with the pandemic still problematic in the United States, the event was canceled. Nevertheless, the HOSR’s 50-year committee found a way to overcome the competition obstacle by bringing together current coaches and competitors at different levels and legendary members of the sport to either talk or write about their experiences through the “50 Years. 50 Stories.” compilation on the www.hosr.org website.

“We put together a committee to brainstorm how to do this … we wanted it to be representative of the breadth of competition and the culture of the HOSR,” Wesson said. “We wanted to hear the stories that have made the legends of the Schuylkill River and Boathouse Row very important to the greater rowing community and very special in our hearts.

“We wanted to celebrate the people of our sport by passing down their stories, not only verbally, but also written stories bridging the past with the present and thereby affecting change for the future of our sport,” she added.

The website has several stories written by contemporaries and legends celebrating the past 50 years of the Philadelphia rowing fall classic along the Schuylkill River. As a sport that celebrates its history with passing its traditions down from generation to generation, and with its “modern” racing origins dating back to 1715 in England, the future and growth of the sport still lies within the youth and collegiate students who participate today.

Army West Point Crew’s Assistant Coach and Equipment Manager Kate Brownson wrote a story for HOSR titled, “Rowing: The Making of an Officer.” The story encompassed the full scope of her experience at West Point from the day she arrived on Nov. 1, 2015 to today in helping build the foundation for cadets to become future leaders of character.

“I’ve learned that so many things correlate rowing with preparation for the Army and leadership (for the cadets),” Brownson wrote in her narrative piece. “Take educating the cadets on the importance of maintaining and properly assembling the rowing equipment so they can fully complete practices or competitions. In the grand scheme of it, failure to properly check or maintain your rowing seat at worst can lead to the risk of losing advancement in competition.

“But the overall lesson learned translates into the cadets’ future occupation, where having successful checks and maintenance of equipment means the better likelihood of a successful mission and you and your Soldiers staying alive,” she added. “I have realized how rowing is a ‘safe space’ where cadets get the opportunity to learn valuable lessons where people’s health and lives are not at extreme risk.”

During this Zoom event, the fourth live episode in the HOSR series, the focus was on the military academies as the ‘Story Hour’ was titled, “Building Leaders + Crews from the Service Academies’ Perspectives.”

The host of the event was Jim Dietz, a rowing legend who won many championship titles, competed in the Olympics and coached at the Coast Guard and Merchant Marine Academies. He was also joined by current and former competitors and coaches from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, U.S. Naval Academy and the U.S. Military Academy.

Brownson was accompanied by Class of 2021 Cadet and team Commodore Alyse Rawls and Class of 2022 Cadet and team Executive Officer Thomas Hilt in the Zoom event.

A couple of other main speakers included one of Army’s first coaches, Mike Weinstein, and the current Coast Guard Academy coach Bill Randall.

The main topic of discussion was the development of leadership in rowing and how the sport plays an integral role in helping shape leaders, especially at the military academies.

Dietz led the session by talking about Brownson’s article and how rowing over the course of time — since the early-1800s at universities in England and mid-1800s in America — has been used at the collegiate level to “Produce leaders who can learn to work together to accomplish a common goal.”

Dietz stated one of Brownson’s emphasis in her article was the key role of the coxswain as the leader of the Eights and the challenge of getting eight rowers to get in sync to fluidly stroke together and succeed as one unit, which he added, “It’s the communication of everyone in the boat and everyone in the squad that makes the mission … a success.”

Brownson wrote, “Stroke after stroke, rowing gives rowers and (the) coxswain the opportunity to learn how to analyze a situation and improve on it. This helps the cadet start to make confident decisions on the fly.”

As Brownson interjected in the Zoom that the building of a cadet’s leadership skills, outside of the military realm taught in the classroom or the field, begins outside of the racing shell, or boat, with the coaches and the cadet staff who help run the team, which supports taking ownership of the squad and fostering a sound team culture.

“From handling their equipment to their uniform to them taking care of the boathouse, these are things that we work with them on,” Brownson said. “We’re really lucky that we get the opportunity to work with them every day. It’s huge for them to think that they’re getting their leadership development … (and) they’re looked at as an athlete or as a rower and coxswain. It’s nice the pressure of where they are in the (class year) rank and everything is left at the door.”

Brownson highlighted that the cadets take onus of leading during the regattas, and those who are leading the team get to, “Feel like they’re leading a company,” which is something not seen at civilian schools.

She said another influential thing is how cadets react to the different scenarios that take place out on the water, good or bad, big or small, and the self-compassion they use as they communicate well with one another.

“There are so many opportunities in our sport that helps with their development,” Brownson said. “The self-awareness is huge in our sport, which is great for (them) becoming an officer and leader.”

Dietz then talked about his experience coaching at two academies, and how there was structure to getting things done without rank at the boathouse. He said classes were blended on the boat with the possibility of a fourth-class cadet in charge of a boatload of firsties, and how organizationally, the culture just worked because everyone had a job to do no matter of one’s experience.

Dietz then posed a question to Rawls about how has her experience with the crew team at Army contributed to her ability to be a great officer and lead Soldiers in the future?

“Before coming to West Point, one thing I was struggling with was my confidence and my self-awareness within myself,” Rawls said. “It’s very important as a rower, as a cadet and as a leader to have confidence because you want people to trust you. My first year, I didn’t know what I was doing because it was the first time I’d ever touched an oar or even touched a rowing machine.”

Rawls, a native of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, said her experience at the Caufield Sailing and Crew Center, which is along South Dock on West Point, has been immense in her overall growth as a person.

“It has meant so much to me how much I’ve grown because of crew and incorporated it in my leadership (style), which is why I believe I got this position (of commodore) because of how much dedication I have to this sport,” Rawls said.

She also liked what Dietz said about what tends to be a role reversal between classes when underclassmen can take charge of a boat.

“I try to teach (the fourth-class cadets) things and then let them teach me things as well,” Rawls said. “Learning to be a follower once again as a firstie, it’s a very humbling experience. That constant exchange I get from the boathouse every single day and every single practice is just awesome.”

Dietz then posed the same question to Hilt with the added, “Did you feel like you had an opportunity to relax,” from the rank structure that cadets are accustomed to at the academy.

“Once I got there, I was approached by a firstie, Grant Hall, and he came up to me and asked, ‘Hey, how are you doing? What’s your name?’ and introduced himself and immediately destroyed all my fear of looking at the senior class who could end my life right there,” Hilt, the Toledo, Ohio, native, said. “He humbled me, he humbled himself and I immediately felt connected to the team and felt this is a safe space where you were going to train, you’re going to become a better person and open up new ways, new opportunities for mentorship that many cadets don’t always get from first-class cadets because of the structure of West Point, up the hill.”

Unlike Rawls, Hilt competed in rowing in high school. Now his biggest assignment as a cow (junior) is to motivate the plebes who come onto the team who have limited to no experience in rowing to have confidence in themselves to do well from the start.

“They show up, they’re physical studs and they’re able to row faster than me, they are able to listen, they’re coachable and being able to approach them and say, ‘Hey, I might have been in the sport for seven years, but what can you teach me,’ so that way I can become better for the whole team.” Hilt said.

Where Rawls talked about paying it forward to the younger rowers, Hilt added about the culture of humility where he tries to get outside the military rank structure to help the functionality of the team.

“This contributes to the idea of brotherhood where we’re all working together to make the boat that much faster, so that we’re that much more successful on the water,” Hilt said. “It’s proving to ourselves that we are capable of things greater than what we can do by ourselves, working together as a team to accomplish fantastic and amazing goals.”

Before Brownson, Rawls and Hilt spoke one last time, Weinstein engaged the audience about his experience of starting the crew program at West Point in 1986. It began with working with the head of the Department of Law at the time to get some old Pocock wooden shelves from the Naval Academy’s scrapyard that eventually helped them put a boat on the Hudson River.

“Over the next three years, we accepted any help we could get, and I know that we visited Jim Dietz at the Coast Guard Academy because we wanted to see what good training facilities looked like,” Weinstein said. “(The cadets) got to see how the Coast Guard cadets lived and it established camaraderie across the branches of service, which was important for the future (of our sport at the academies).”

Now, fast forward 35 years later, the crew team is not only great competitively, but it is a great source of helping develop and prepare these cadets, who were civilians not so long ago, into excellent officers one day.

“These people know they have to develop. They have four years to figure it out and become adults,” Brownson, who rowed at West Virginia University, said. “There are some people in their 40s who still haven’t figured out how to be an adult. They’re 18-year-old kids who are still figuring things out.

“I think that’s what’s great is they realize that they need to mature faster and quicker, and figure it out,” she added. “I think about who I was when I was 18 to 21 years old, and I can’t imagine having that pressure put on myself to develop that much quicker, so I’m really proud of them.”

Then Dietz asked one more question to both Rawls and Hilt by querying, “How do you envision rowing helping you prepare to be officers?”

Hilt jumped in first by saying rowing brought him into wanting to be a part of the military profession and go to West Point while he was in high school. He said he understood what it took and the effort needed to have a successful outcome in either physical fitness or academic success for ultimate professional excellence.

“Ever since I came to West Point, every opportunity I’ve had to physically accept, train, work hard has led me to being successful,” Hilt said. “There is nothing like being successful in the professional side of being in the military and preparing to become an officer.”

Hilt added that the crew team allows each cadet some sort of autonomy and an attachment to the organization because it is completely run by the cadets with guidance and mentoring by the coaches.

“We are practicing leadership every single day,” Hilt said. “Either as team leaders, squad leaders, platoon leaders, company commanders, executive officers, we’re practicing these skills that are going to help us once we become PLs leading America’s sons and daughters into the crucible of ground combat.”

Rawls spoke about a former teammate, Mary Barr, who is an engineer officer now. She said how Barr positively talked about how crew alumni would come back and tell stories about surviving ordeals like Ranger School because “I had times in crew where it was much harder than right now.”

“Reflecting on statements like that and then seeing the history of the last couple of years of what crew has been producing — we have Rangers, we have Sappers and other accomplishments within the crew on the officer side,” Rawls said. “It teaches us, ‘Wow, if we can produce athletes like this, I can’t imagine what kind of leaders myself, Thomas and the other cadets on the team are going to become once we leave the academy and graduate.’”

Social Sharing