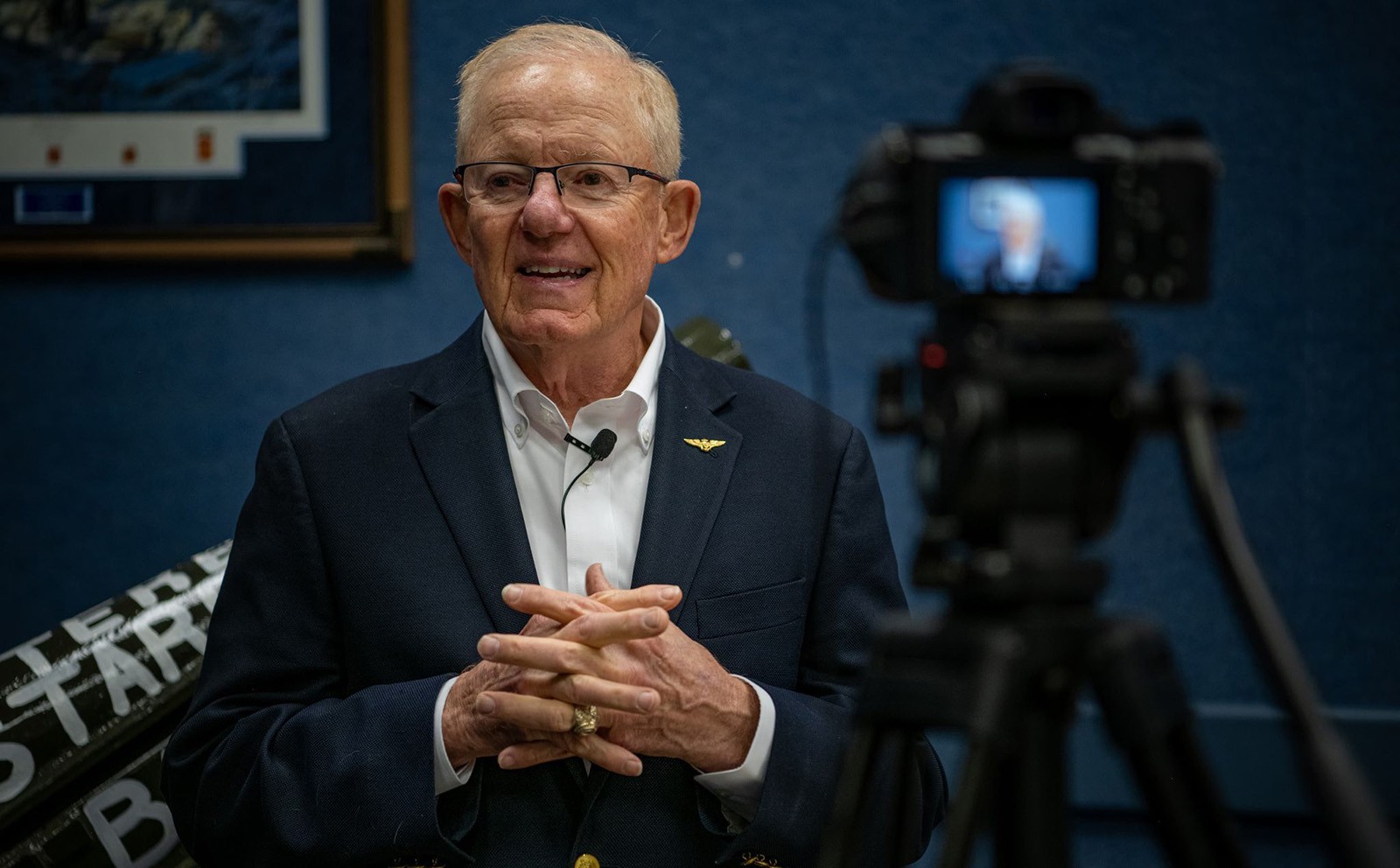

FORT SILL, Okla., April 13, 2021 -- Retired Navy Capt. Charlie Plumb spoke about his experiences as a Vietnam War fighter pilot and prison of war to Field Artillery Captains Career Course (FACCC) Class No. 1-21 students April 8 in Snow Hall.

The captain flew 74 successful missions either dropping munitions over North Vietnam or flying close air support sorties to assist U.S. Army and Marines units in South Vietnam. Some of those sorties were to support field artillerymen such as those seated before him.

“The reason those missions were the most gratifying is we could hear the (forward air controllers) and (fire support officers) and they were overjoyed,” said Plumb.

With only five days left of his eight-month tour aboard the U.S.S. Kitty Hawk, Plumb was shot down near Hanoi, then the capitol of North Vietnam. He became a prison of war (POW) for 2,103 days in the infamous Hanoi Hilton prison camp.

“The challenges you face today and the ones you will face in the future are the very same challenges that I faced in that prison cell,” said Plumb.

Scanning the room and making eye contact, Plumb said all the students seated before him have at times felt overwhelmed or underappreciated.

“There’s not a person in here who hasn’t felt some guilt for not quite measuring up to the task or who didn’t quite complete that mission,” he added. “That’s the way I felt.”

Plumb spoke of the humiliation and guilt that enveloped him as he endured torture and interrogations. Quickly he learned to lie to his interrogators when he knew they couldn’t possibly know the correct answer. The other times he told the truth and avoided a lot of pain.

Plumb then acquainted the audience with his life in an 8-foot-square prison cell, one of several cells that he lived in for six years as a POW.

He arrived in dreadful shape – wounded, thirsty, hungry, and losing weight fast – as temperatures exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit. He called that the good news, because the bad news was far worse: He had given up and surrendered.

Time passed very slowly as he paced the tiny cell with a constant barrage of physical, mental, and emotional pain wearing him down. Plumb said he eventually learned to get used to the cramped space.

“The restriction isn’t the 8 feet between those walls,” he said. “The restriction is the 8 inches between your ears.”

So, he set to making a deck of playing cards using toilet paper that he quipped was hard to shuffle. He also went places in his mind or visited family. Anything to pass the time.

Then one day he heard what sounded like the chirping noise of a cricket. Instead it proved to be a small wire scraping the floor. Plumb deduced the enemy wouldn’t be trying to trick him so it had to be another prisoner trying to communicate with him. Even as the relief filled him that he wasn’t alone, Plumb’s mind began to fill him with dread. He thought the other prisoner was probably a higher ranking officer, a better pilot, and one who stuck to the Code of Conduct instead of “spilling his guts,” as Plumb feared he did.

Plumb said he didn’t feel like comparing himself and asked the audience if they ever felt that way.

“I guess we all do at times. You don’t want to get involved because you believe you’ll get humiliated, outsmarted or outmaneuvered.

He said those little fears can confine us and prevent breakthroughs from happening, but sometimes you have to “kick down what’s left of your comfort zone.”

So Plumb gave a small tug on the wire and felt a tug back. The wire then disappeared but came back later with a small piece of toilet paper affixed to it. On it was a five-by-five grid surrounded by numbers 1-5 and the letters of the alphabet within, along with instructions to memorize the code then eat the note. With that code, prisoners could talk by giving tugs on the wire or knocks on a wall to represent which row and column a particular letter was. The recipients could then spell out words that led to conversations and even lessons on various subjects.

That means of communication led Plumb to becoming part of a team determined to endure their captivity and leave it with honor.

To reach that goal, Plumb asked the audience what tools they could draw from in their psychological toolbox to help them survive. They responded with mental toughness, God, discipline, desire, creativity, a purpose, will power, and a sense of humor.

“Those are qualities you can’t measure or learn in a textbook,” he said. “It is values we’re talking about: It’s Fires 50.”

Plumb said he entered the prison at age 24 and left at age 30. How he left a better man he summed up with one sentence. “Adversity is a horrible thing to waste.”

Of that long ago war and it’s after effects, Plumb said it gave him a purpose to share his story that formed the rest of his life. But it was lessons learned growing up of discipline and forgiveness that helped him get through captivity. He said he forgave the North Vietnamese many years ago and has even returned to Vietnam with other veterans.

Plumb accepted the speaking request from his son-in-law Marine Maj. Jonathan Bush, a FACCC instructor. Working as a motivational speaker since his retirement from the Navy, Plumb has shared his Packing Parachutes message of hope and resiliency to over 5,000 audiences in business, government agencies, media, and other fields.

Social Sharing