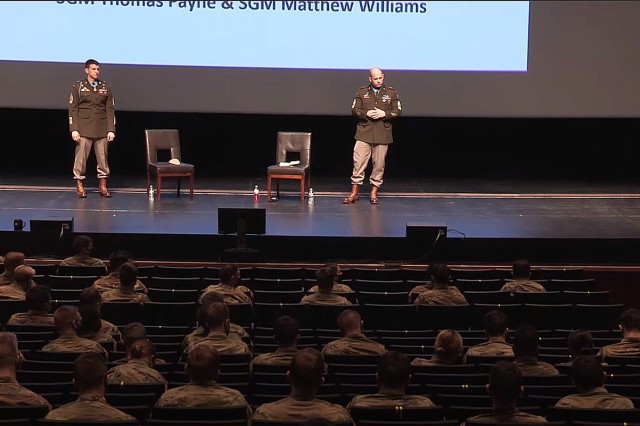

“Today, you have an opportunity to hear from two extraordinary noncommissioned officers who happen to be Medal of Honor recipients,” Commandant Brig. Gen. Curtis Buzzard said as he expressed his excitement for guest speakers Sgt. Maj. Thomas Payne and Sgt. Maj. Matthew Williams, who imparted insight on their military career and practical leadership advice to cadets on behalf of the Modern War Institute Commandant’s Speaker Series at West Point on March 17 in Eisenhower Hall Theatre.

Col. Patrick Howell, the director of the MWI at West Point, took the podium and introduced the two Medal of Honor recipients to the Class of 2021 cadets. The theatre echoed with applause as the NCOs came on stage.

Silence fell upon the theatre. Payne’s story was the first to be told.

In the fall of 2015, the Kurdish regional government had reached out to the United States in need of support for a hostage rescue mission. Payne was a sergeant first class at the time when his unit, as part of a special operations task force, was tasked with conducting the rescue operation alongside Kurdish partners and U.S. Special Operations Command to rescue 70 prisoners on Oct. 22, 2015, in Hawija, Iraq, Payne explained.

“For this mission, I was an assistant team leader. My team was responsible for one of the buildings that the house was being held in. What was significant is that there were freshly dug graves (outside the building) and if we didn’t action this target, the hostages will probably be executed,” Payne said. “At that point, it was our duty to bring those men home. That’s when you make that transition from Soldier to warrior; that’s when all the joking stops. That’s when you do your last-minute checks, that’s when it’s game time.”

Payne’s unit planned, trained and equipped themselves with all the tools they would need to execute the mission accordingly. Every contingency needed to be considered. There was no room for complacency. Payne’s team embarked on the helicopters and flew to the hostage location, Payne said.

“Ramp drops, it’s a complete brownout. Part of the compound was already in a pretty intense firefight. As we maneuver to our building, we throw out the ladders,” Payne said. “The other part of our team maneuvered over to their blind positions. That’s when we hear that there was a man down, and it was Master Sgt. Josh Wheeler.”

Payne’s medic relocated back to the other team’s position to administer Wheeler some aid. Meanwhile, Payne and his team pressed forward to free the hostages in the first building. One of Payne’s team members looked him in the eye and said, “Follow me.” Payne’s team was able to secure the area due to light resistance. The team stood before the locked cells that held the captives. He cut the locks. There were 25 prisoners in one cell and about 11 in the other, Payne said.

“You see their faces light up, and they’re being liberated,” Payne explained. “Some are crying, some are excited. And while this is going on, there’s still an intense firefight going on in the other building. You can see the flames, you hear the all the explosions going on. You hear on the on the radio an urgent call for assistance. And that’s when I looked at a teammate to tell him, ‘hey, let’s get in a fight, so let’s go.’”

Payne and his team went to the roof of the burning building where the second team previously requested medical assistance. West of their position and down below the building where they stood, they continued to receive constant fire from the enemy. Shouting from Payne and the enemy continued as small arms fire and grenades were employed by Payne’s team at the enemy combatants below, he said.

Payne was unable to enter the building from the roof.

They quickly moved under fire to the first floor and attempted to breach the walls and windows. As they worked their way into the building, the team began taking casualties.

“Once you are able to control your fear, that’s the bridge to personal courage and courage is contagious on the battlefield,” Payne said. “One of the teams was holding down the breach point all the way down to their last magazine. Bullets were passing through the uniforms. I’m peeking the breach. I see the same prison door that was on the other building.”

Payne knew that if he attempted to cut the prison door lock, he would expose himself to enemy fire. If he didn’t cut the lock, the hostages trapped inside would be burned alive. Payne called for bolt cutters while his team members effectively covered him. They began engaging the combatants in the back room. There was a small foyer Payne was able to maneuver through and cut the top and bottom locks of the prison door, Payne added.

An evacuation order was given over the radio. It was becoming harder to breathe through the flame and smoke. The heat was becoming more and more overwhelming. The building was beginning to collapse, Payne said.

“My sergeant major pulled the guys from one of the rooms and I’m, like a third base coach, waving them through the initial breach point. I snatched an ISIS Flag off the wall and stuffed it in my pocket. I see that the train of hostages have stopped so I grabbed him and moved through the breach point to get the hostages going. I went back into the building and noticed that one of the hostages had basically given up on life. He was over 200 pounds — a big fella. So I grabbed him by the collar and drug him through the breach point. Then I ran back into building for one last check.”

Payne had confirmed that everyone was out of the building. Payne and his team successfully extracted all 70 men and took off on the helicopters. There was so little space in the helicopters that Payne and his team had to stand for the rest of the ride, Payne said.

“The Medal of Honor I received symbolizes everything that is great about this country,” Payne said. “For me, I don’t consider myself a recipient of this medal, I consider myself a guardian of this medal.”

Comparably, Williams was engaged in a similar predicament back on April 6, 2008.

It was very early in the morning. The 3rd Special Forces Group was assigned with a mission to kill or capture a high-value commander, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the leader of Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin, who was located in Shok Valley, Afghanistan, with an undetermined amount of combatants.

The helicopter arrived at the designation point. An element of the team move forward to go up the mountain near the village while Williams and his Afghan commandos stayed at the riverbed.

“I remember specifically at that point, those of us in our element that was down in the riverbed, we immediately found cover behind some rocks. It was just kind of quiet, and then all of a sudden, everything exploded all at once,” Williams said. “Machine gun fire, some RPGs started going off and then we started returning fire up toward the village, that’s kind of when things started getting a little haywire.”

Williams joined the small counter-assault team led by Master Sgt. Scott Ford to assist the wounded, higher up on the mountain. As soon as they got up there, they quickly realized that teammates Dylan and Luis were shot; everyone else hunkered down and had decent cover.

“Scott and I, with the captain, looked around, trying to figure out exactly what we wanted to do, how we’re going to get the wounded guys out of there and then see what made sense from that point,” Williams said. “I went down about halfway, called a couple more of our guys, and then asked them to bring more commandos up. Basically, we made a chain to help pass these casualties down because they were going to be on litters.”

Suddenly, Ford and Staff Sgt. John Walding were shot as Williams and the commandos arranged to transfer the two casualties down the mountain under heavy fire. Williams assessed that situation, figuring out how he and his team would engage the enemy while taking care of casualties.

“Scott was ambulatory, meaning he could walk, he’d already had a tourniquet put on his upper left arm where he was shot, so I was basically able to get him up on his feet and then helped him climb down. I gave him to Staff. Sgt. Seth Howard, and asked him to take Scott to a little house down toward almost at the river bottom,” Williams said. “The house served as a casualty collection point but was difficult to reach because of enemy fire and steepness of the rocky terrain.”

Williams moved back up the mountain again to get Walding.

“That’s where John was. He’d been shot in the leg, it was basically amputated,” Williams said. “So I went back down about halfway again, trying to establish a corridor to move these guys through. I knew we couldn’t go up the same way that I’d gone the other times, just because we had been getting pretty heavy fire. So there was a cliff face that went around a little outcropping. I realized if we could scale across that, we can get onto this outcropping and then we’d be able to come up from behind where those other guys were.”

Williams took the new path back up the mountain, not knowing what they would find when they returned to their teammates. Once Williams reconvened with everyone, Howard pushed forward with his sniper rifle and provided cover fire. Sgt. David Sanders, who was in the middle of the formation, had found a safe route downward. As they made their way down, Williams and Sanders continued moving casualties. They made sure they had all of their gear and then made their way down, Williams said.

Williams added once he and his teammates reached the casualty collection point, they continued to take heavy fire from the enemy.

“We had to hold our ground the best we could so that the medevac birds were comfortable enough flying in to exfiltrate those casualties,” Williams said. “The (medevac) were taking fire the whole entire time, so they were awesome pilots, but they came in and, really, I mean they saved the day helping those guys get out of there.”

Williams and his team spent six hours heavily engaged in combat against 200 enemy sentries. Luckily, no Army Soldiers were killed during the conflict, he added.

“I think it’s an honor for me to receive (the Medal of Honor) on behalf of the Special Forces regiment, really,” Williams said. “I hope to continue positively representing the regiment and really help get the story out about what us Soldiers are actually doing on the front lines and what Green Berets are actually capable of.”

As the event continued, the questions and answers portion began. Class of 2021 Cadet Gregory Drake took the microphone and asked, “How do you build trust with partner forces who might be Kurdish or who might be Afghani? There are these cultural barriers between not only you but also your subordinates and also the partner forces. How do you build trust between that to bridge those cultural gaps?”

Williams said it is about contextualizing the core of what it means to be human. Building relationships based on one’s humanity is the key to bridging that gap between cultures.

“My first trip with Afghani Commandos — it’s kind of the light infantry unit of Afghanistan — these guys, they are warriors and that warrior mentality is what they relate too, so we have an opportunity in that to share a common bond and that bridges that gap to let us learn each other’s culture just by sharing that initial moment of camaraderie,” Williams said. “The rest of it is just sheer relationships. You have to be willing and able to deploy forward, find your partner force, link up with them and invest in that partnership for the amount of time that you’re there. That is something that (Special Forces) take seriously.”

Class of 2021 Cadet Ryan Murphy asked, “Both of you have talked about how important the warrior identity is to yourself and to your team. Can you talk about the difference between a warrior and a Soldier and how you best instill the warrior identity in your teams? Also, in what situation is it best to embody each of those identities?”

Payne said there is a transition once your boots hit the ground on the battlefield. It’s a total mentality shift.

“When I’m about to engage in a battle, I personally go through my mental rehearsals of the battle plan over and over again,” Payne said. “I also run through my checks of contingencies that I might face and just being prepared to action those contingencies when that time comes.”

Social Sharing