FORT BENNING, GA – “It was scary, but I knew I wasn’t going to lose him.” A mother’s faith sustained her through the most terrifying week of her life, as her 10-year-old son fought off a rare but serious COVID complication in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

Spc. Olubisi Abisoye’s son Enoch woke her up in the early hours of Friday February 12 saying he did not feel well. “Something’s wrong, something’s definitely wrong,” Enoch said. “My body was too hot, my head was spinning as if something had just hit me in the head. I wouldn’t normally wake someone up at 5 a.m. unless it was an emergency, so it was an emergency.”

Abisoye treated her 5th grader with Tylenol for his headache and fever, and Pepto Bismol for his upset stomach. But when he wasn’t feeling any better by two in the afternoon, she brought him into the Emergency Department at Martin Army Community Hospital (BMACH).

The entire family had tested positive for COVID in January, but have since recovered. The doctors still needed to rule it out due to Enoch’s symptoms. Thankfully, the nasal swab for COVID came back negative. So did the tests for flu and strep. When his 103 degree fever finally broke around 10 p.m., the doctors discharged him.

Abisoye said her son seemed fine over the weekend, but started complaining of a headache again on Monday. This time, she also noticed rashes. When he started throwing up Monday night, she thought it best to make an appointment to see his Primary Care Manager. Since Enoch was suffering from COVID symptoms, they took him to the Pediatric Respiratory Urgent Care Clinic (PRUCC).

PRUCC Provider Capt. Brandon Pye quickly assessed the child’s multiple symptoms and rushed him to the Emergency Department. “His vital signs were so abnormal. His blood pressure was low,” said Pye. “His heart rate was markedly elevated. He was lying down with his eyes closed not spontaneously talking or moving a lot.” Enoch’s mom credits this early intervention and the BMACH staff for saving her child’s life.

“Within a few hours, his vital signs just started dropping,” Abisoye said. “It was bad. He got everybody scared. He was in so much pain, he was crying and yelling. Luckily we had wonderful people on shift that day. They had ten people attending to him to make sure he was okay.”

Now began the mad scramble to find out exactly what was wrong. “They had to send his blood to the lab for examination. They did an MRI. The first one that came back was his COVID. And he tested positive.”

Turns out Enoch had developed a rare but serious complication associated with COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is a condition where different body parts can become inflamed, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes or gastrointestinal organs. The CDC does not know what causes the rare complication, but since mid-May 2020 has reported a spike of 2617 cases. What they do know is more than half the reported cases of MIS-C, 59 %, are in males and most are in children and teenagers between the ages of 1 and 14. The CDC said MIS-C has also disproportionately affected children who are Hispanic, Latino or Black.

“The doctors discovered he had inflammation in different organs. I was really scared,” Abisoye said. “He was having difficulty breathing so they gave oxygen and epinephrine to him to help him … because at that time he couldn’t really breathe.”

BMACH reached out to children’s hospitals in both Atlanta and Auburn, only to be told their beds were full and couldn’t take any critical COVID patients. Fortunately, Children’s of Alabama in Birmingham had beds and were already treating patients with MIS-C.

“Because of the urgency of the situation, they had to bring the helicopter to take him over there,” said Abisoye. “They took him to the Pediatric ICU in Birmingham around 11 p.m.”

With her son medevacked to Birmingham, mom took off on the solitary three hour drive. “The drive was not the problem for me. The problem for me was I was so anxious to see him,” shared Abisoye. “I’m not a medical person. I don’t know what to expect. I don’t know what’s the worst that can happen. So that feeling of uncertainty of things scared me.”

Mom said she prayed all through that night, and the following nights. “I didn’t get to see him until two or three in the morning. When I got to his room, as soon as I opened the door, he was half asleep. He opened his eyes and he squeezed my hands.”

BMACH Nurse Care Manager Tami Story said two infusions of immunoglobulin finally stopped Enoch’s body from attacking itself. Enoch was so sick, he wasn’t even able to get out of bed until Thursday. The nurses were afraid of him falling. “At least I wasn’t as shaky,” said Enoch. “So I could go to the bathroom and walk back and forth. I wasn’t scared. I remember seeing all the beautiful lights during the helicopter ride.”

The boy who loves to eat anything and everything said about 50% of his hospital diet was Sprite. “Most of the stuff I ate, I mostly vomited,” explained Enoch.

“He couldn’t taste anything,” added Abisoye. “They brought him different things. But he was like ‘no.’ But when they brought him Sprite, he could actually taste it. So every time they asked him what he wanted, his answer was Sprite.”

“All I cared about was him. I don’t even know what time it is, I don’t know what day it was,” said Abisoye. “Most of the four nights I was there I stayed awake to watch him, make sure nothing happened.

“My greatest fear was the side effects. When this year started God didn’t tell me I was going to lose my child. I knew he was going to make it, but I didn’t know what MIS-C was. Because COVID is so new, the doctors can’t really say this is what happened 20 years ago and this is how we deal with it. And this is what we should do. So that IF was the big problem for me as a mom.”

Enoch was discharged from Children’s of Alabama on Saturday February 20. He is on the mend, but must undergo repeat bloodwork and see a rheumatologist in Birmingham to watch for inflammation and any long-term damage.

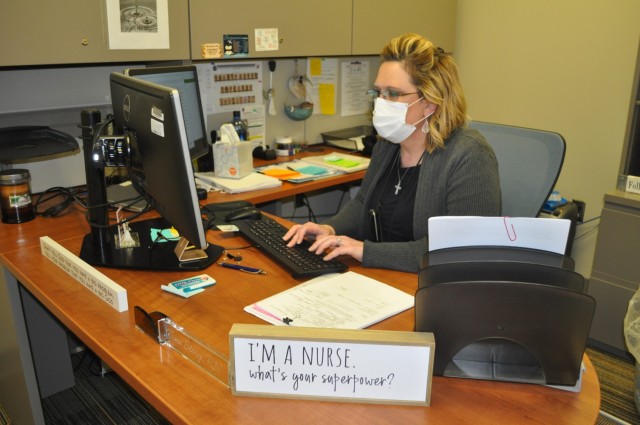

Story is helping the Abisoye family negotiate the myriad of follow-up appointments. “I’ve been working with the doctor there. We’ve had to get frequent labs, I send him the results … it’s a multi-team thing,” said the pediatric nurse care manager. “I am the advocate for the patient. I help take the stress off of the parent.”

Social Sharing