November 1950 opened with the U.S. Army in hot pursuit of the shattered remnants of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA). Since their bold landing at Inchon on September 15, 1950, United Nations (UN) forces had soundly defeated the Communist invaders and were pursuing the retreating enemy north toward China. Unbeknownst to the UN troops, a change was coming that would soon change the tide of victory into a fighting retreat. Early in November, lead elements of the UN drive began encountering pockets of Chinese troops. Despite evidence that the Chinese had entered the conflict, American intelligence seemingly discounted the signs and UN forces continued to attack. By November 25, it was apparent to the soldiers of the Eighth Army Ranger Company fighting stubbornly to hold Hill 205 that the operational situation had changed drastically.

When the Korean War began, the U.S. Army faced a fierce and determined enemy, one highly skilled in the use of infiltration tactics. The NKPA particularly excelled in conducting night attacks behind American lines. Having deactivated all of its special operations units at the end of World War II, the Army decided to form new organizations to meet the combat requirements posed by the NKPA threat. In only a few weeks, the Far East Command (FECOM), led by General of the Army (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur, directed the establishing of new Ranger and Raider companies to counter the North Korean threat.

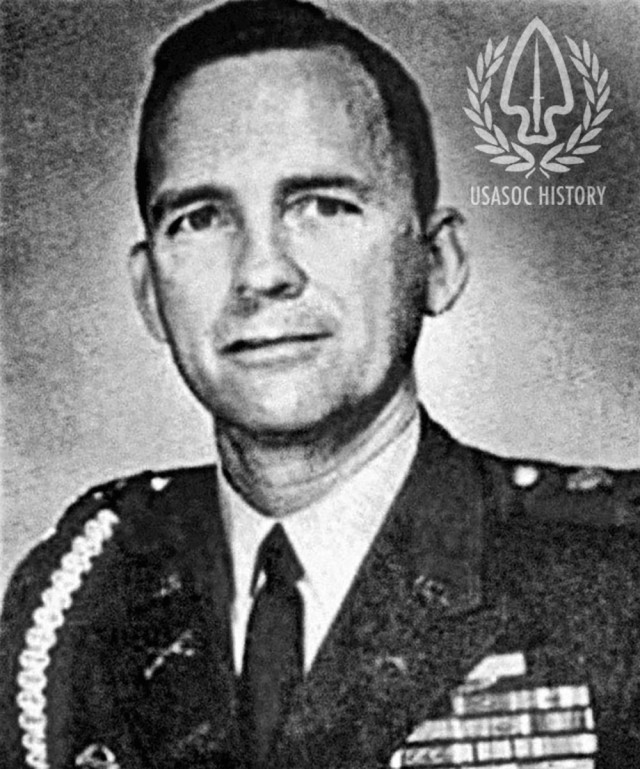

Within FECOM, Col. John H. McGee, a veteran of the U.S. led Philippine guerrilla campaign during World War II (WWII), was tasked to select, form, and train new special operations units with skills in raiding and infiltration. McGee established a Ranger training center near Kijang, South Korea, and screened volunteers to fill the new units. In quick succession, a General Headquarters (GHQ) Raider Company formed on August 6 and an Eighth Army Ranger Company was activated on August 25, 1950. After an intense training period, both were quickly committed to combat.

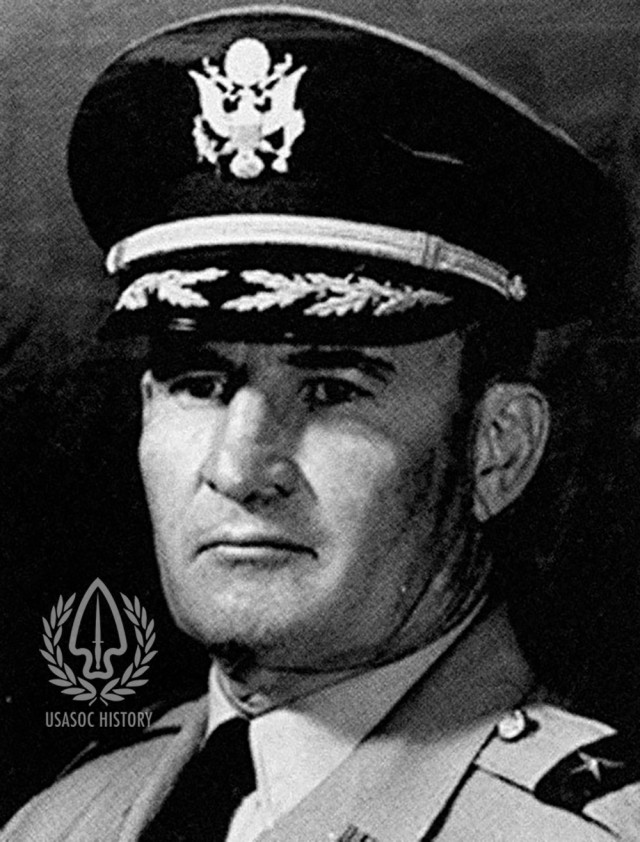

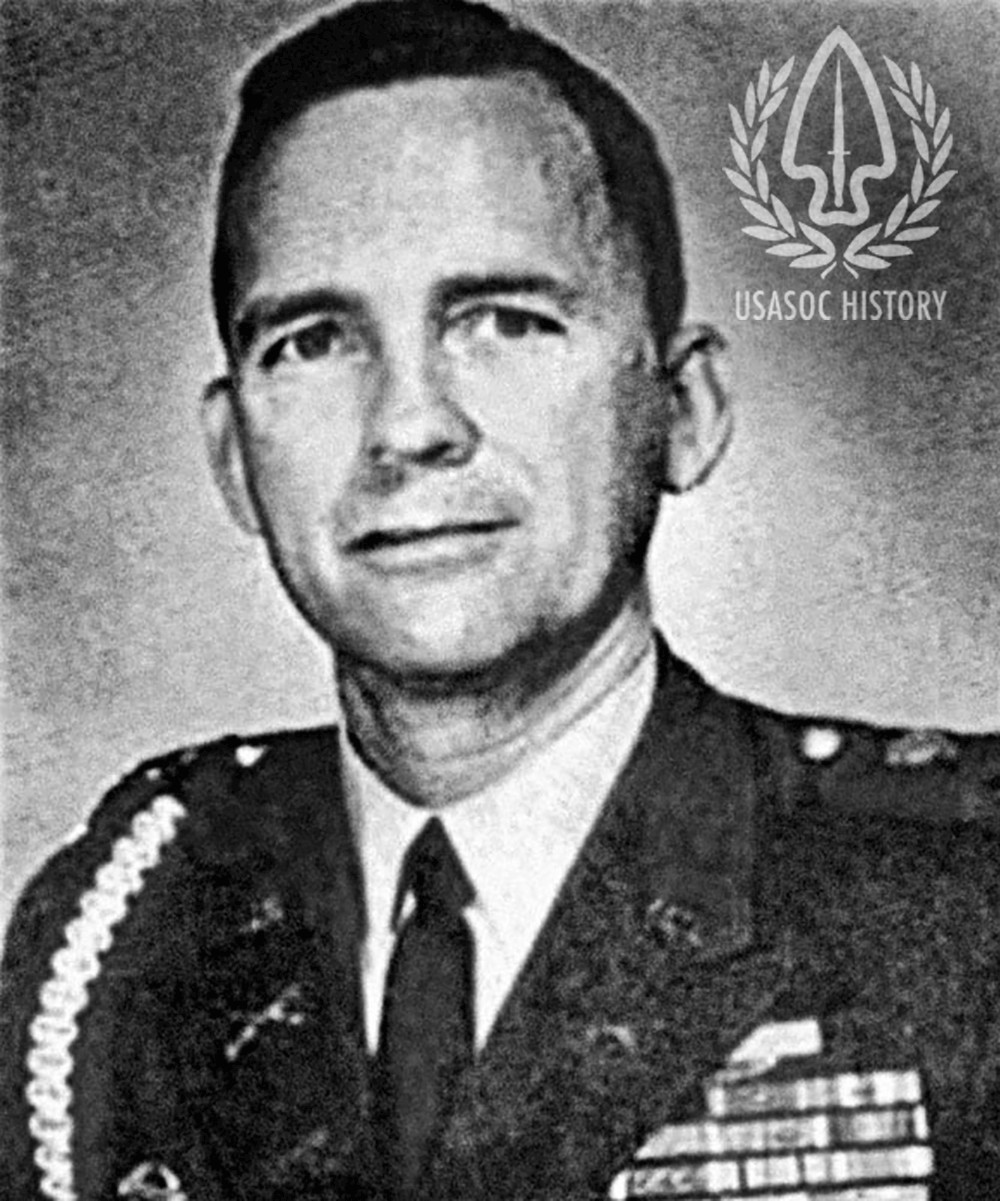

In addition, the U.S. Army created Ranger Infantry Companies (Airborne), modeled after the successful WWII units of the same name. A new Ranger Training Center (RTC) was established at Fort Benning, Georgia, on September 15, 1950, and the training cadre was in place by September 23. Soon after, the first four companies of volunteers arrived to begin Ranger training. The plan at that time was for units to complete training as companies, which after graduation, would be assigned to support a specific Infantry Division. The RTC could effectively train four Ranger companies at once. The officer selected to command the RTC was WWII veteran infantry regimental commander Col. John G. Van Houten, and his deputy was the former First Special Service Force commander Col. Edwin A. Walker.

When the success at Inchon led to the rapid collapse of the North Korean forces in the south, the various Ranger companies ‘cut their teeth’ conducting counter-guerrilla operations against NKPA stay-behind elements that were wreaking havoc in UN rear areas. Ranger units were also used to guard the flanks of advancing forces and to secure particularly difficult objectives. By mid-November they were experienced and confident, and helped to push the Communist forces back. Some optimistic observers were predicting the fighting would be over by Christmas.

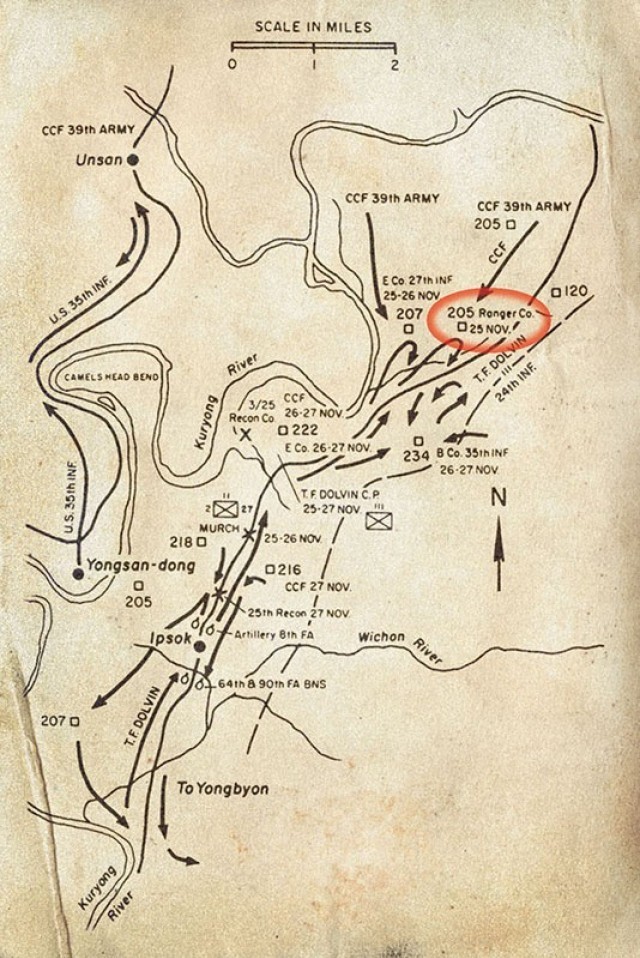

But Chinese intervention in the war changed all of that. By November 20, the Chinese Army had infiltrated hundreds of thousands of Chinese “volunteers” into North Korea, and had clandestinely positioned four armies in front of the still advancing UN forces. A new phase of the war was beginning. One of the Chinese armies, the 39th, was poised to blunt the forward progress of the 25th Infantry Division, at that time crossing the Ch’ongch’on River and moving north. At the point of the 25th Division movement was the understrength Eighth Army Ranger Company, led by 2nd Lt. Ralph Puckett, Jr.

With orders to seize and defend Hill 205, the Rangers moved out in the early morning hours of November 25, in temperatures that dropped below zero. As Puckett’s men approached the hill, Chinese mortars began to bracket their positions. Calling in their own artillery, air strikes, and tank direct fire support to break up the enemy attack, the Rangers suddenly found themselves exposed, their nearest friendly unit having fallen back several kilometers behind them. Puckett recalled, “I felt all alone, but totally focused on my direct responsibilities and prepared to hold the high ground.” Digging in, the Rangers primed themselves for the worst, which soon came. At that very place and time, the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) began their all-out assault of American positions all along the lines. Surprised and overwhelmed, UN forces began retreating across the front. However, the Rangers held their ground, even improving their positions throughout the rest of the day.

That night, beginning at 2100 hours, swarms of CCF soldiers blowing bugles and beating drums launched the first of six human wave assaults against Puckett’s beleaguered Rangers. Receiving his first of several wounds in the initial attack, Puckett refused to be evacuated, and remained to direct the defense, and stubbornly repulsed the Chinese masses. Soon after, a second wave hit, then a third, each one leaving the Rangers with less men and ammunition. Soon after midnight, Puckett issued the order to fix bayonets. Although worn out from fending off five separate human wave assaults, where he received a second wound in the shoulder, Puckett made his way along the shrinking lines. The Chinese then launched their sixth major attack. Under the fresh onslaught, the few surviving Rangers were pushed off the hill. Puckett, with wounds to both feet, his thighs, buttocks, and left shoulder, found himself being carried down the hill by two of his men. They had to desperately fight their way through throngs of Chinese to finally rejoin survivors at a collection point at the base of the hill. There, he was evacuated and his role in the war was over. For his valorous actions in holding Hill 205 and repulsing five major attacks, Puckett earned his first of two Distinguished Service Crosses.

The Battle for Hill 205 illustrates the changing situation that came to define Phase 3 of the Korean War (November 3, 1950 - January 24, 1951). With the massive influx of CCF, UN units were pushed back all along the front and the Allies were forced to retreat below the Han River and regroup. Frustratingly, the UN forces again pulled back below the South Korean capital of Seoul, and watched Communist soldiers seize that city for the second time in five months. The setback would cause the war to grind on for two and a half more years before ending in an uneasy Armistice on July 27, 1953. Furthermore, the stalemated attrition warfare of Phases Four and Five would effectively end any need for highly maneuverable Rangers or elite infantry. By the end of 1951 all Ranger organizations again disappeared from Army formations, not to reappear until combat requirements in Vietnam forced their reactivation.

For more information regarding the activities of the Eighth Army Rangers, GHQ Raiders, and the six Ranger Infantry Companies (Airborne) that fought in Korea, see: https://www.arsof-history.org/arsof_in_korea/index.html. In addition, there are many other articles dedicated to the history of these special units and the incredible achievements of the soldiers who fought in them.

Social Sharing