FORT SILL, Oklahoma (Nov. 5, 2020) -- A successful businessman who seemingly had it all, and then gave it away after he became a meth addict and burglar, was the guest speaker Oct. 26-30, at Fort Sill.

Damon West, author of “The Coffee Bean,” spoke to thousands of Soldiers ranging from basic trainees to drill sergeants to junior officers to senior leaders and civilians during dozens of presentations.

He drew from his prison experiences in a Texas maximum security penitentiary as he spoke about finding opportunities in adversity, and combating three corrosives to teams: suicides, racism, and sexual assaults.

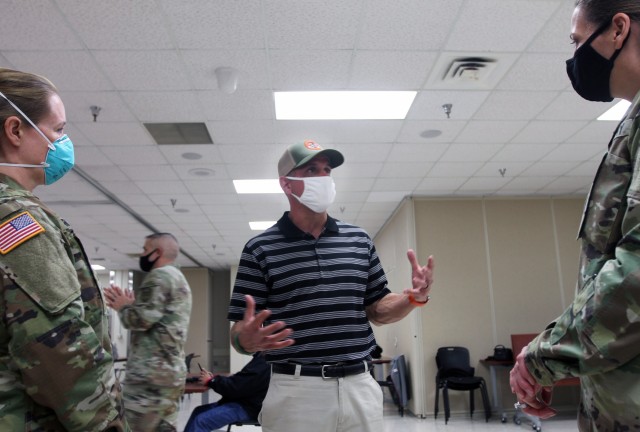

West, who was paroled in November 2015 after serving over seven years of a 65-year sentence, spoke to a group of medical professionals Oct. 30, at Reynolds Army Health Clinic.

The social hierarchy of the inmates at the Mark Stiles Unit in Beaumont, is completely opposite of mainstream America, said West, who played quarterback at the University of North Texas. Blacks are at the top followed by Hispanics. At the bottom tier are whites.

“It (Stiles) is a very difficult, very dangerous place to do time,” said West, formerly inmate No. 1585689.

Right after his six-day trail in May 2009, West’s mother said: “Baby, debts in life must be paid. You just got hit with one hell of a bill from the state of Texas."

She also said West owed her and his father a debt. “When you go to prison you will not get into one of these white hate groups … you won’t get any tattoos. Damon, you come back as the man we raised, or do not come back at all.”

Before he was transferred to Stiles, West was in the Dallas County Jail where he met career criminal Mr. Jackson. Jackson, in his 60s, told him what to expect at the penitentiary, and how to survive.

Jackson’s words were: “You don’t have to win all your fights, but you do have to fight all your fights.” That became West’s mantra, he said.

Carrot, egg or coffee bean

Jackson also told him that in prison he can become either a carrot, an egg, or a coffee bean. He said to imagine the penitentiary as a pot of boiling water. He said a carrot in boiling water gets soft, mushy, and weak. It gets robbed, raped, beaten, and maybe killed.

“You don’t want to be the carrot in prison,” Jackson told West.

Jackson said an egg becomes hard boiled. Inside that shell is a core that was soft liquid, but has now has hardened.

“If your heart becomes hardened you’re incapable of giving or receiving love,” Jackson said to West. “If you become hardened your parents won’t recognize you because your shell will have swastikas all over it.”

What happens with a coffee bean?

“Now you have to change the name of water to coffee because the smallest of these three things, like you West, has the power to change it,” Jackson told West.

“The power was inside the coffee bean, just like the power is inside of you,” West told the audience.

Suicidal

Six weeks into Stiles, West said he felt like a broken man from constantly fighting gangs. He went to the volunteer chaplain, an 84-year old woman, and told her he was going to kill himself.

“I thought this out. It would be easier for my family who could visit a grave site rather than visiting me in prison. I can’t do this for 65 years; it’s too dangerous, it’s too hard, West said.

“That day she told me the secret of faith: If you’re going to pray, don’t worry. If you’re going to worry, don’t pray. You can’t have it both ways.”

West said he grew up in a mixed neighborhood in Port Arthur, Texas, and it wasn’t uncommon for him to be the only white child at a party or on playgrounds.

In the Stiles’ recreation area, the inmate-imposed racial hierarchy is in place, West said. “It’s the most segregated place that I’ve seen before or since.”

Only blacks are allowed to play basketball. One day after a game, West pounced on the ball and refused to give it up. Inmates were cursing him and spitting on him. Finally, one of the leaders said West could take a free throw; if he made it he could pick a team.

“If I missed the shot they were going to kill me because I had just disrespected every black at the unit,” West said. “If I make the shot they’re going to let me play.

“It was nothing but net,” West said of his free throw.

West said he picked his team and thought it would be 5-on-5, but it was 9-on-1 against him. There was no referee, no such thing as a foul; you can punch, bite, pull hair, West said.

After the game he had a bloody lip and bruises, he said.

In subsequent games, West would always be the first player picked so he could get roughed up on the court, he said. “I felt like a piñata.”

This lasted for six days with him rarely getting to touch the ball. Then one day he took a shot and missed, but he was later given the ball again and made it.

“Good shot, West, good job, man,” said a teammate.

Then everything changed. The blacks were much more relaxed. One of them told him that he never quit, he took all the abuse, but he never got racial.

“I survived,” he said. “I learned two things about adversity: It’s never as bad as you think it’s going to be, and two, you’re capable of way more than you think you are.”

One day his cell mate, Carlos, told him word was out that an inmate, Black Jack, was going to rape West in the showers. Black Jack was 6-feet, 4-inches, HIV positive, and he uses a knife. That was his M.O., West said.

To be forewarned is to be forearmed. Carlos fashioned a ball-and-chain using West’s personal fan motor and a mesh commissary sack. West used the improvised weapon to successfully defend himself in the shower. When he left his cell the next morning he never had to fight again.

“One of the things about sexual assault is that violence usually goes with that,” West said. “They saw that I could speak violence, which is the only language everybody speaks in a maximum security prison.”

Justice system

West, who has a master’s degree in criminal justice, and who teaches at the University of Houston, said if you look at any prison population in America, almost half the inmates are black men.

Black men only make up 6.5 percent of the U.S., West said. The numbers say that one out of every four black men are in the criminal justice system.

“You mean to tell me that 6.5 percent of the population commits 50 percent of the crime?” West said. “Hell no, y’all.

“There is not one criminal justice system in this country, there are a lot of them,” West said. “There is a black one, there is a white one, there is a brown one, there is a poor one. Hell, there’s one for cops. It depends on who you are, and where you fit in that spectrum.”

Positive change

West provided tips for people to create positive change.

Change your mindset, and your attitude toward things, he said.

“I had to stop looking at prison as my punishment, but look at it as my opportunity,” West said. “If I can be a coffee bean in prison, you can be a coffee bean out here.”

Have positive body language, he said. The first thing it affects is you.

Get up everyday and work out in three areas: physically, spiritually, and mentally, West said.

Be a servant leader, West suggested. “It’s helping other people achieve their goals in life. When we’re helping other people, that’s when we are at our best.”

Know what you control and don’t control in life. “You control exactly what you think, what you say, what you feel, and most importantly everybody is going to see what you do,” West said. “If it’s not inside your head, you don’t control it.”

Your past does not define you, West said. “Your past is a lesson, the present is a gift, not to you, but what you can do for other people.”

The toughest prison in America is the prison in your mind, West said. “More people are imprisoned by their thoughts and by their things than by steel bars or barbed wire.”

To avoid being a prisoner of your mind put values and a belief system in front of your mind, he said. The Army has already given you one, its seven core values.

Afterward, Col. David Zinnante, Fort Sill Medical Department Activity commander, thanked West for his inspirational words, and he presented him with his coin of excellence. Then West mingled with guests.

Social Sharing