October is National Disability Employment Awareness Month, and the month is focused the contributions Americans with disabilities makes to our Army. But, did you know that, CECOM’s mission and the Signal Corps can be traced back to one man’s attempt to improve life for the deaf population?

Albert J. Myer received a medical degree from the University of Buffalo in 1851, with his medical dissertation, “A New Sign Language for Deaf Mutes.” Myer had worked in a telegraph office while studying for his degree, and transformed the Bain telegraph code into a means of personal communication by spelling out words with taps on a person’s hand or nearby object. After joining the Army in 1854 as an assistant surgeon, Myer converted his sign language system into the flag and torch system which became known as “wigwag.” This system, unlike semaphore signaling, relied on a single flag, which was easily transportable and used a limited number of personnel. In 1860, the bill authorizing the creation of the Signal Corps was signed, and Myer, promoted to Major, was placed in charge. From communicating with the deaf to communicating across distances, Myer’s work significantly contributed to the development of Army communications.

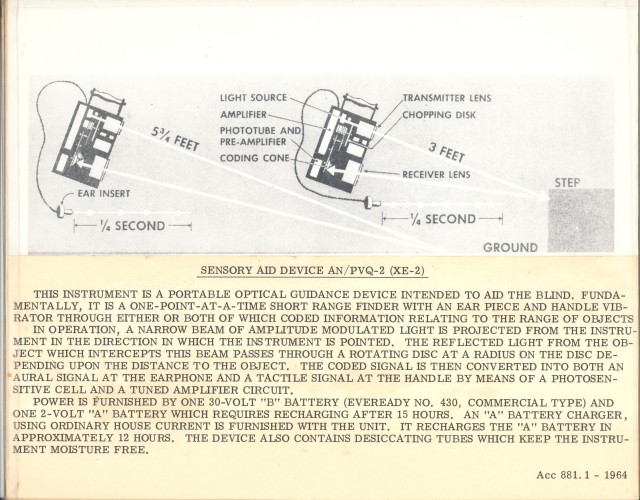

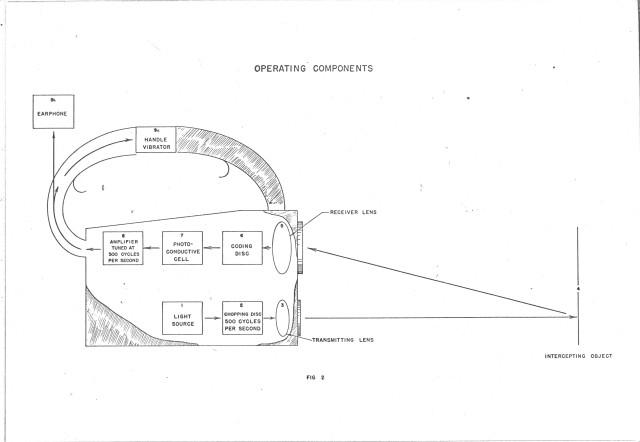

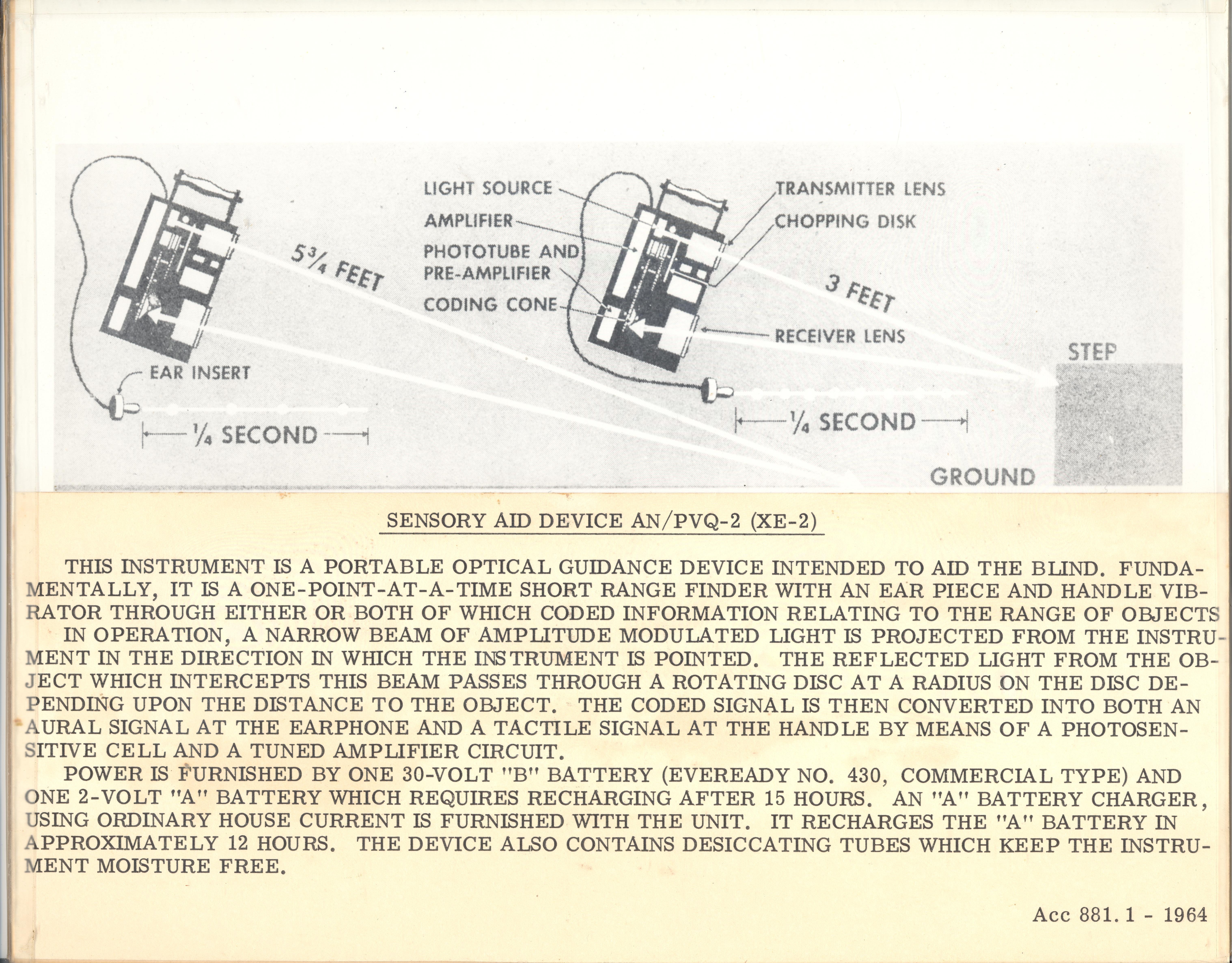

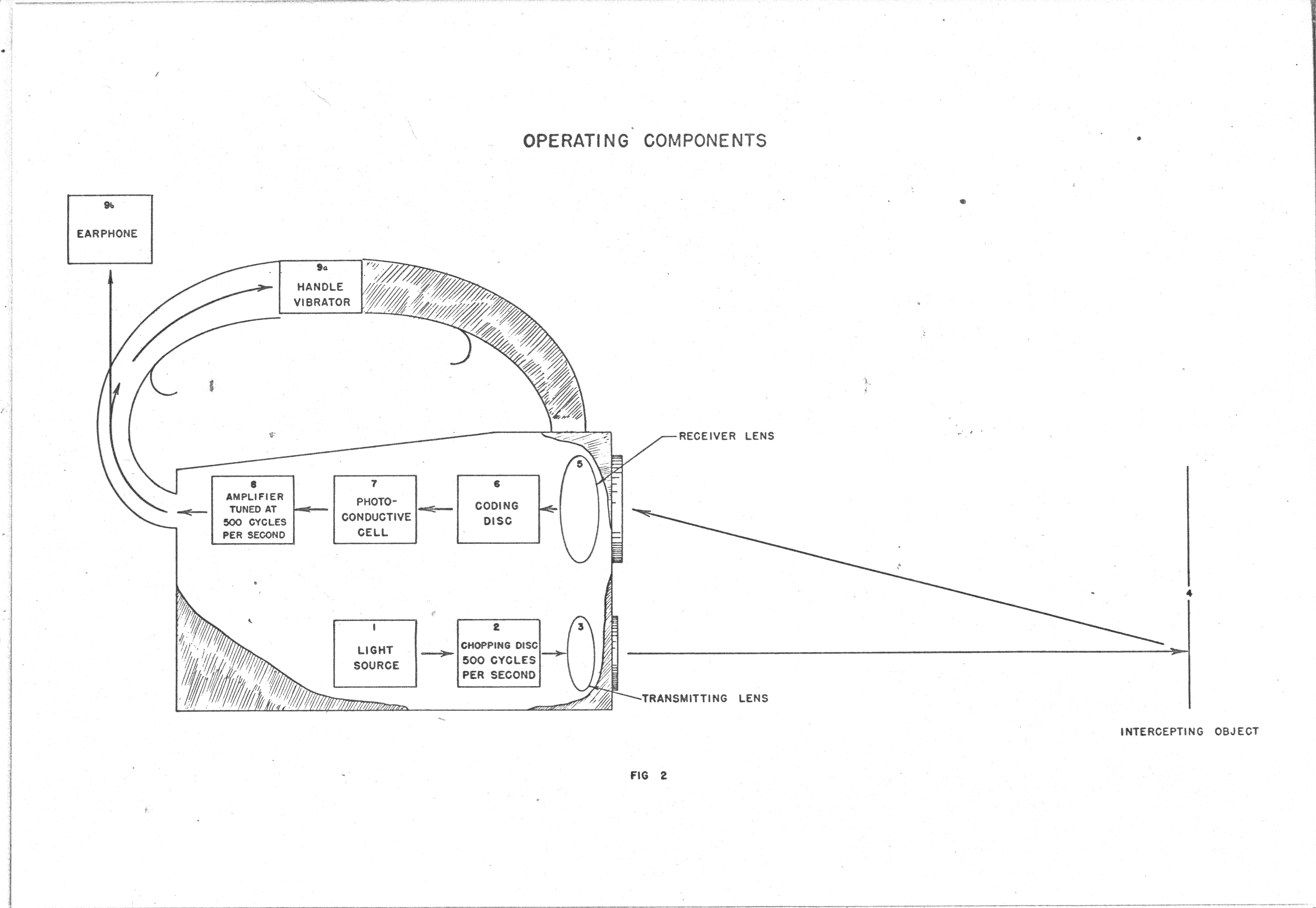

Moving forward almost one-hundred years, the well-established Signal Corps was on the cutting-edge of communications equipment research and development, with most of this research taking place at the Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, NJ. In 1945, Signal Corps Electronics Laboratory physicist Lawrence Cranberg developed what was called the Sensory Aid Device, AN/PVQ-2. An outgrowth of personal radar sensory aid AN/PPQ-1 (Operational radar, personnel detection), meant for nighttime use for soldiers on patrol, the Sensory Aid Device was considered to have potential for civilian use. About 25 of the devices were built for the Veterans Administration, which submitted them for further testing.

The AN/PVQ-2 used a pulsed beam of light which, when reflected from an object, impinged upon a photoelectric cell. This cell in turn would set off either an audio signal or a vibration, which the user detected in an earphone or through the handle of the device. The aid was unaffected by non-pulsed light, such as sunlight and ordinary electric light. The intent was to allow the user to “sense” the physical environment, including straight lines (curbs, buildings), steps, and doorways, to assist the user in navigating common obstacles. The hand-held device weighed about 9 pounds and was equipped with an ear piece. Though it was never developed commercially, the device lead to further experimentation on devices to assist with non-visual navigation.

These examples help illustrate the basic idea of National Disability Employment Awareness month – that good ideas and contributions can come from anywhere and anyone. In the quest to improve communications technologies, the Signal Corps has benefitted from the contributions of wide range of individuals – Army doctors, scientists, engineers, Soldiers and civilians. The Army draws from the technologies being developed by industry, and in turn, produces unique military equipment that ends up being broadly adopted by society at large.

Social Sharing