FORT SILL, Oklahoma (Sept. 24, 2020) -- “Personal courage is contagious on the battlefield.”

A quote like that means more coming from a Special Operations Soldier who helped save the lives of 70 Iraqi hostages on the verge of being executed by Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) insurgents. The above words came straight from the lips of the newest recipient of the nation’s highest and most prestigious award for valor, the Medal of Honor, Sgt. Maj. Thomas “Patrick” Payne.

Payne was the chalk leader aboard a CH-47 that flew into ISIS-controlled territory Oct. 22, 2015, for one of the largest hostage rescue operations in history. One of his battle buddies, Master Sgt. Josh Wheeler of Oklahoma, died in a firefight while on that mission, and he, too, received the Medal of Honor. Payne called Wheeler “a phenomenal noncommissioned officer.”

“You have to go there with a clear mind, you have to think about completing the mission,” Payne said of his own transformation from Soldier to warrior.

He noted that Wheeler gave the command for his team to run to the sound of the guns. Payne would go on to say that Wheeler manifested the Army value of selfless service by valuing the lives of the Iraqi hostages above his own, and Payne honored his memory by naming his own son Josh.

Payne considers himself a guardian of the Medal of Honor, not a recipient, because that helps ease the burden. Lt. Col. Jason Carter, director of the Fort Sill commander’s planning group, said afterward that that statement shows the speaker’s humility.

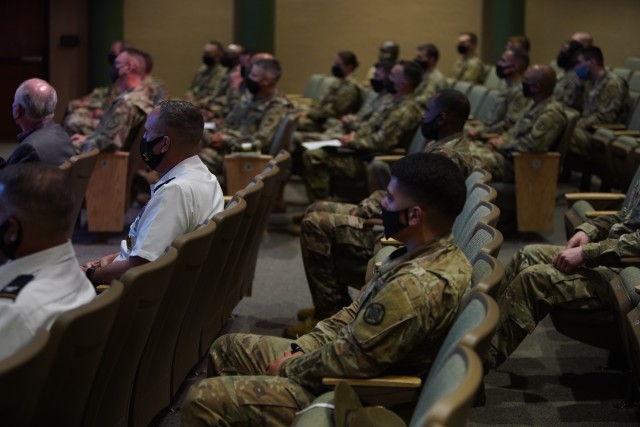

Fort Sill wasn’t the first stop on Payne’s worldwide speaking tour, but it was the first installation, Carter said. Because of COVID-19, a pathogen nobody had heard of until this year, Payne’s speaking tour had to be live -streamed rather than live.

Soldiers who submitted queries before the cutoff were admitted to Snow Hall’s Kerwin Hall for socially distanced seating, and Reimer Conference Room was only one of several locations around post accommodating the overflow. As Carter read each question, the Soldier who asked it stood up so that Payne could see them on his end of the stream. If more than one Soldier asked the same question, they rose together.

Fifteen minutes before start time, Maj. Gen. Kenneth Kamper, commanding general of the Fires Center of Excellence and Fort Sill, asked how many Soldiers present had ever had interaction with a Medal of Honor recipient before. Only three hands went up.

Payne, an instructor assigned to the Special Operations Command, grew up in Batesburg-Leesville and Lugoff, South Carolina, and graduated from high school in 2002.

As a high school senior when the Twin Towers fell, he felt a strong sense of duty to serve his country. Upon graduating high school he enlisted as an infantryman and completed the Basic Airborne Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 2002. He completed the Ranger Indoctrination Program, now known as the Ranger Assessment and Selection Program, in early 2003.

He was then assigned as a rifleman to A Company, 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, where he also served as a sniper and sniper team leader until November 2007, the year he was selected for assignment to the Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Since then he has served as a Special Operations team member, assistant team sergeant, team sergeant, and instructor.

In 2012 Payne and his teammate won the Best Ranger Competition, a grueling contest that places extreme demands on buddy teams’ physical, mental, technical, and tactical skills as Rangers at Fort Benning.

Throughout his career, Payne deployed 17 times in support of Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, New Dawn, Inherent Resolve, and to the U.S. Africa Command area of responsibility. He earned a bachelor of science degree in strategic studies and defense analysis from Norwich University in 2017. He is now stationed at Fort Bragg where he lives with his wife and three children.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, live-streamed from Oklahoma City, provided opening remarks for the session. He thanked Payne for making Oklahoma one of his first visits after receiving the Medal of Honor Sept. 11, 2020.

Stitt highlighted Wheeler, a Sequoyah County native, for making the ultimate sacrifice to protect those in danger and to preserve the freedom Americans hold dear.

“His actions will never be forgotten,” Stitt said. “Sgt. Maj. Payne, y

our heroic actions inspire all of us. We will forever be grateful for your service to America, and on behalf of all 4 million Oklahomans, we thank you.”

Payne described the events of Oct. 22, 2015, matter-of-factly, putting the emphasis on his teammates rather than himself. His description of how he grew up was classic small-town America – “hunting, fishing, you had to play sports to kind of stay out of trouble.”

In response to a question about the biggest obstacle he had to overcome, Payne said, “Believing in myself.” He admitted that early in his career he had trouble with that and had to build himself up.

A separate question prompted Payne to describe how he persevered through a career setback just two years before winning the 2012 Ranger Competition. Injured by a grenade in Afghanistan, he credits his parents for getting him through the recovery process.

It was a grueling time, he recalled. One knee was completely scarred over, and he couldn’t bend it enough to do a full rotation on a bicycle. His dad brought an old stationary bike down from the attic and made him get on it every day to break up the scar tissue. His wife, a three-sport athlete in college, got him running again.

These were some nuggets of advice Payne had for his audience: “Be there for each other, on and off the battlefield … Know your job. Do it to the best of your ability … Leadership is inspiration. Inspire each other.”

When asked for advice on building and maintaining trust within an organization, Payne concentrated on how to keep trust rather than prevent its erosion, because once trust is lost it’s harder to build it back up. You have to build relationships because relationships matter, and that’s his center focus as well as for the noncommissioned officer corps.

“You have to foster an environment where our Soldiers feel comfortable about speaking up about difficult topics,” he said.

At one point Payne said he intends to stay in the Army for 25 years before sitting down with his family to assess what his retirement might be like.

Asked why he continues to serve, Payne said, “I fell in love with the job. I fell in love with the day-to-day operations as a Soldier, and I’ve had the honor and privilege of now serving as a noncommissioned officer and serving you as a sergeant major. It’s been great, and I’ve had the opportunity to reach out to a lot of Soldiers in this past week, and that’s a pretty unique opportunity.”

At the end of the professional leader development event, Kamper asked Soldiers to sum up their reaction to the speaker in just a few words. Here’s what they came up with: “Humility … team worker … building relationships … sense of duty … Army family … lead with empathy and equality … balance your personal life with your professional life.”

Social Sharing