MADISON, Wis. – To commemorate the end of World War II 75 years ago, the Wisconsin National Guard is recounting the role of the 32nd Division. Consisting of the Wisconsin National Guard and much of the Michigan National Guard, the division spent more days in combat than any other American unit against a determined enemy and unforgiving terrain.

“I doubt if anyone, anywhere, is more profoundly moved by this news than the men of this division, who have fought so hard, suffered so much and waited so long for this moment.” – Maj. Gen. William Gill, 32nd Division commander, on Japan’s surrender, announced Aug. 15, 1945.

Members of the 32nd “Red Arrow” Division, like other American forces in the South Pacific, awaited orders sending them to Japan to conclude the final chapter of the Second World War. Those orders never came after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima Aug. 6, 1945. Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced his surrender Aug. 15.

On Aug. 30, Gen. Douglas MacArthur emerged from an unarmed C-54 aircraft that had brought him from Melbourne, Australia, to Atsugi, Japan, and lit his corncob pipe. Descending the stairs, he met Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, whom MacArthur once directed to take Buna or not return alive.

“Bob, from Melbourne to Tokyo is a long way, but this seems to be the end of the road,” MacArthur said.

From the Owen Stanley Mountains in New Guinea to Luzon, Philippines, the 32nd Division had walked that long, winding and deadly road for 654 days of intense combat, more than any other American unit. Two Red Arrow Soldiers in the 128th Infantry Regiment were killed in Banzai charges Aug. 15, the same day Hirohito broadcast his surrender.

Maj. Gen. William Gill, 32nd Division commander, communicated with Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, who commanded all Japanese forces in the Philippines, to arrange the surrender of Japanese forces. Yamashita replied that he had received no official authorization to enter surrender negotiations, but acknowledged that he instructed his subordinate units “insofar as communications were possible” to cease hostilities.

Col. Merle Howe of Grand Rapids, Michigan, who on separate occasions commanded the 126th, 127th and 128th Infantry regiments and was described by Eichelberger as a “stalwart fighting man,” died Aug. 30, 1945, while in an airplane that crashed due to engine failure while delivering messages to Yamashita.

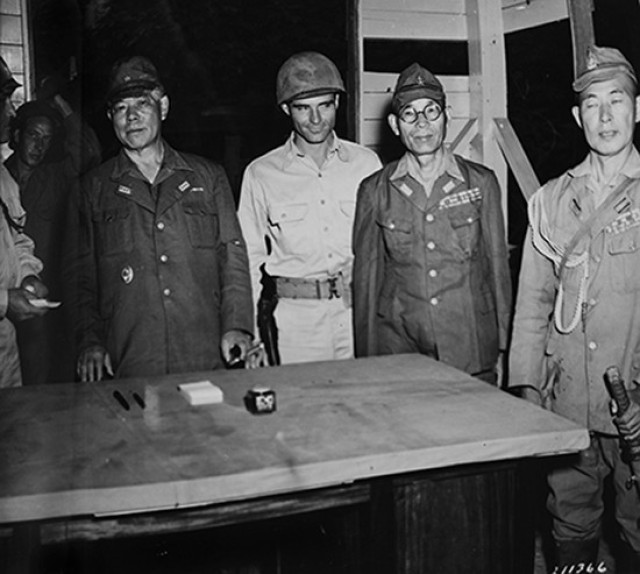

First Lt. Russell Baumann of Glenbeulah, Wisconsin, leading a 24-man detachment from Company I, 128th Infantry Regiment, met Yamashita and his staff on a hilltop near Kiangan, Luzon, at 8 a.m. Sept. 2, when Yamashita officially surrendered to the 32nd Division.

“I have the honor to inform you that I have been charged with seeing you and your party through our lines without hindrance, delay or molestation,” Baumann said. Through an interpreter, Yamashita replied, “I want to tell you how much I appreciate the courtesy and good treatment you have shown us.”

While in Kiangan, Yamashita’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Akira Muto, asked about the Red Arrow insignia. Col. Ernest Barlow, the 32nd Division’s chief of staff, explained the significance of the Red Arrow piercing the impenetrable Hindenburg Line in World War I, which inspired the design of the insignia.

“Yes, and the Yamashita Line in World War II,” Muto is said to have replied.

“It was entirely fitting that the 32nd Division should receive the vanquished enemy,” Eichelberger would later write. “Three years before at Buna, they had won the battle that started the infantry on the jungle road to Tokyo.”

Gill was not on hand for the surrender – he had already turned over command of the 32nd Division to Brig. Gen. Robert McBride. Yamashita and his staff were taken to Baguio, Luzon – Yamashita’s headquarters – for a formal surrender ceremony Sept. 3.

During his subsequent interrogation by Sixth Army, Yamashita indicated he considered the 32nd Division to be the best Soldiers his men faced at Leyte and Luzon.

Even though the war was now officially over, the Red Arrow was not ready to return home quite yet. The 32nd Division did indeed advance to Japan, landing at Kyushu on Oct. 9, 1945, to begin occupation duties. In January 1946, the division learned it would be inactivated in Japan and began turning occupation duties over to other units. The 32nd Division was formally inactivated Feb. 28, but reorganized later that year in Milwaukee. The Red Arrow was federally recognized as a National Guard division once again Nov. 8, 1946.

The 32nd Division claimed the following records during World War II:

- 654 days of combat, more than any other division in the war.

- 15,696 hours of combat, more than any U.S. division in any war, and 48 percent of the total time the U.S. was in World War II.

- Six major engagements during four campaigns.

- 41 months overseas, with more than 21 months in combat.

- Responsible for 35,000 Japanese soldiers killed in action.

- 11 Medals of Honor.

- 157 Distinguished Service Crosses.

- 49 Legion of Merit.

- 845 Silver Stars.

- 1,854 Bronze Stars.

- 98 Air Medals.

- 78 Soldier’s Medals.

- 11,500 Purple Hearts.

“I’m proud of these men who fought at Buna, at Saidor, the Drimiumor, on Morotai, on Leyte and on Luzon,” Gill said in the division’s newspaper Aug. 16, 1945. “I also think this is an appropriate time to remember the sacrifice of the men who died in those battles. This is their moment, too.”

Epilogue

The 32nd Division would be called to federal service one more time in its history. On Oct. 15, 1961, exactly 21 years after it was called to federal service for World War II, the Red Arrow reported to Fort Lewis, Washington, to prepare for potential deployment to Europe amid the Berlin crisis.

In 1967, 50 years after it first organized for World War I, the 32nd Division was inactivated and reorganized as the 32nd Separate Infantry Brigade. Nearly all the Wisconsin Army National Guard’s current units trace their lineage to the 32nd Division, and the Red Arrow remains the largest formation in the Wisconsin National Guard today.

In 1986, the 32nd Brigade became the largest National Guard unit to participate in a REFORGER (Return of Forces to Germany) exercise.

The Red Arrow’s legacy continued into the next century, as it played a major role in the global war on terror in the years after Sept. 11, 2001. Elements of the 32nd deployed to Iraq multiple times before the entire 32nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team deployed in 2009 to various camps in Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

The Red Arrow added another chapter to its storied legacy in 2019 and 2020 when it deployed two of its infantry battalions to Afghanistan.

The brigade also continues to respond to emergencies in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

Social Sharing