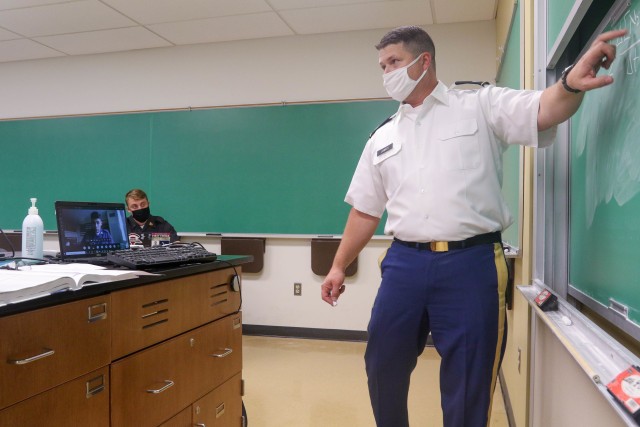

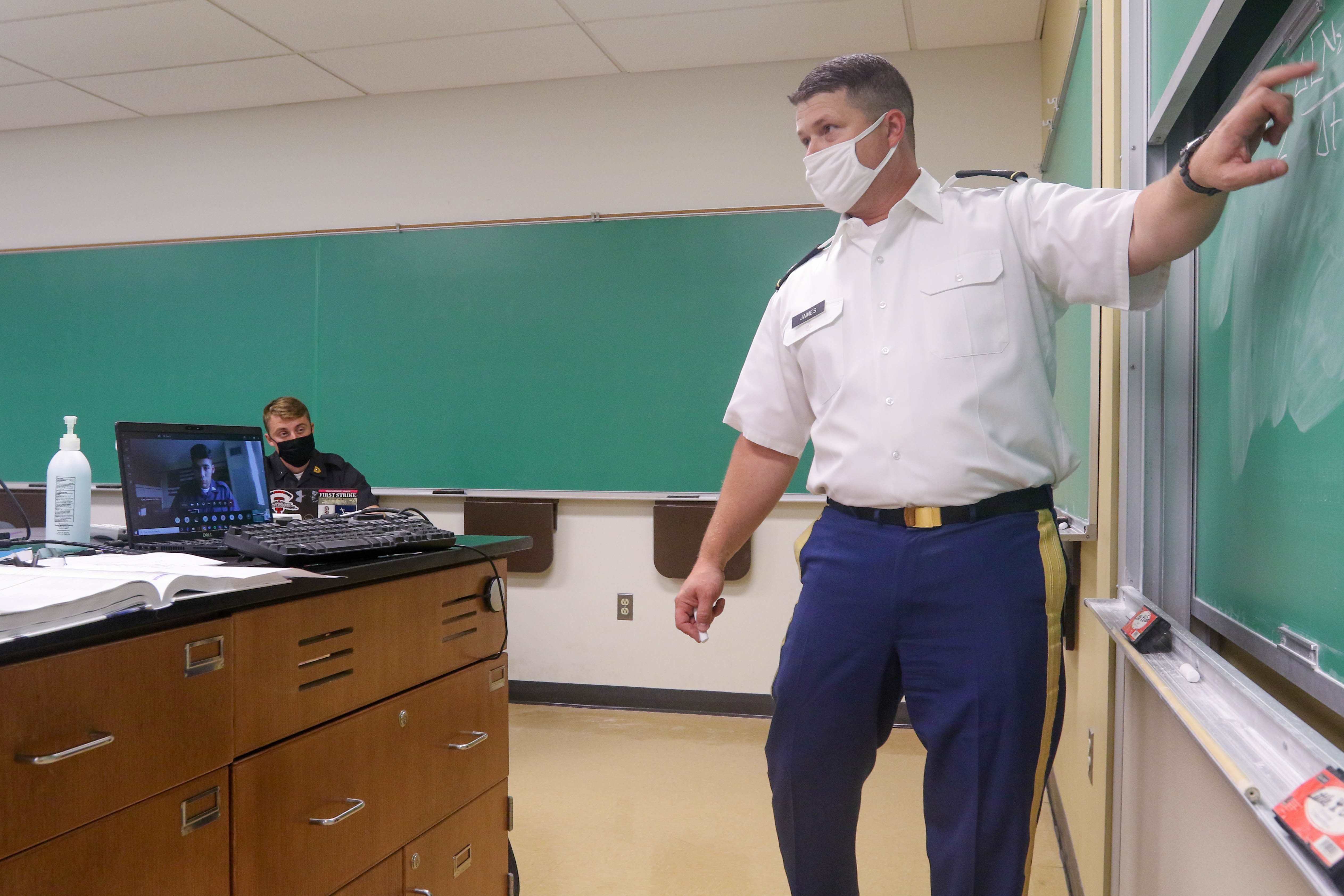

Standing in front of his class in Bartlett Hall, Lt. Col. Corey James begins to write a chemistry equation on the board. He has already gone through the administrative details that are required on the first day of a new class. Now, he is teaching the first lesson for cadets in General Chemistry II.

A white mask covers his face as he moves the chalk board up and down to help the full class see the equation he is working through. Eight cadets sit spread out in the classroom with black masks covering their face. Only half the seats are full and purple Xs cover the tops of the other half of the desks marking them as off limits.

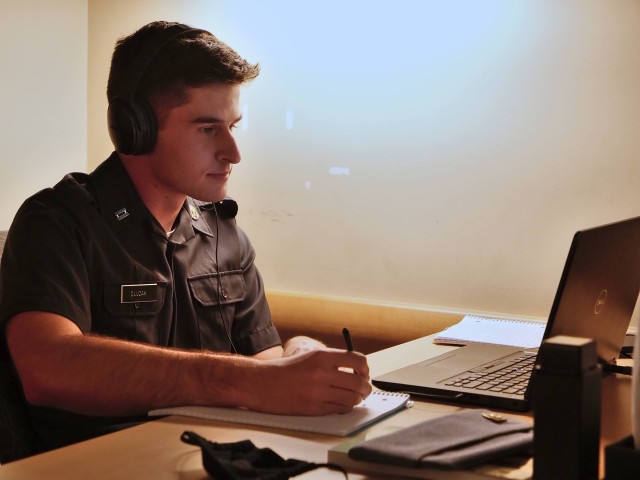

As he works through the equation, Class of 2023 Cadet Chloe Zendt pops up on the projector screen in the right corner of the room and her voice comes from the laptop James has positioned so the camera can see the chalk board. Watching the class from her barracks room, Zendt has a question about the work being done.

This is the new reality as the U.S. Military Academy starts a new academic year in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. The full General Chemistry II class includes 16 cadets, but for each class period only eight will attend in person and the other eight will attend via Microsoft Teams. Then, the next time they will switch places.

“It was easier than I thought, but I prepared a lot,” James said after teaching two courses that include cadets both in person and remote. “The other thing that really helped is the cadets were very professional. They had prepared themselves, so they were paying attention and they were reacting to what I was saying. It was better than I thought. We have some technology we're going to keep working on here, but it was pretty good.”

These new hybrid classes are just one of the ways West Point has adapted for academic year 2020-21. Cadets attending the first day of classes Monday was the culmination of a monthslong planning process that began in April. The first step, said Col. Michael Yankovich, the vice dean for operations, was developing possible scenarios for the fall semester. A small team of professors was assembled and given the task of developing different scenarios of what the conditions could be in the fall based on what was known about COVID-19.

The final determination was to build the plan based on the academic year starting at Health Protection Condition Bravo, Yankovich said. HPCON Bravo means there is a low to moderate threat of community transmission of the COVID-19 virus, but necessitates protective measures being put in place.

The first of those protective measures was cadets being tested for the virus and then placed in a controlled monitoring period when they arrived at West Point. That process created a bubble-like atmosphere within the Corps of Cadets.

During the planning process, it was determined additional protective measures were required once the academic year began because the staff and faculty at the academy includes people of various ages and medical histories who will not be living in the same type of bubble, Yankovich said.

“We can’t keep staff and faculty in the bubble on West Point, every day, day in and day out,” he added. “Knowing that drove a couple of things. That drove us to make the decision that we will really want to emphasize non-pharmaceutical interventions as we go into the academic year.”

Along with deciding to start the year at HPCON Bravo, Yankovich said they made the assumption early on that cadets would be back at West Point prior to the beginning of the semester and crafted plans to try and facilitate as many in person classes as possible.

Once Superintendent Lt. Gen. Darryl A. Williams officially made that decision, they were able to begin planning in earnest and set a process into motion that allowed classes to begin as scheduled Monday morning, even if it doesn’t look like a typical academic year.

“We are executing every single class,” Yankovich said. “There have not been any classes dropped.”

The most noticeable difference is cadets and professors are now required to wear masks in academic buildings. An extra five minutes has also been added between periods to allow for additional disinfection of all horizontal and shared surfaces in the rooms.

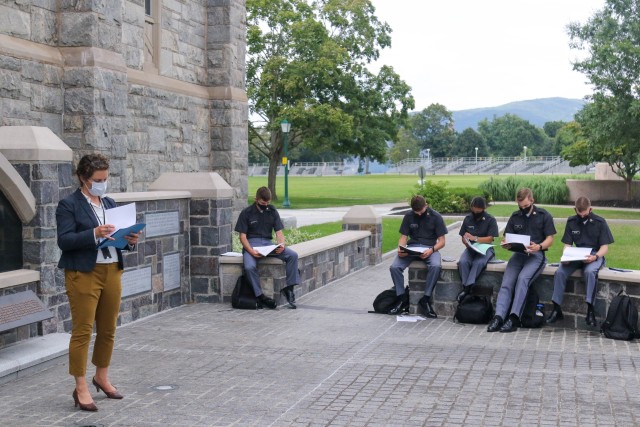

The protective measures also required changes to how cadets will be taught during the fall semester. About 50% of classes will be taught entirely in person. Many of those require hands-on instruction such as science labs, engineering courses and military science classes.

The rest of the classes will have at least some virtual components because social distancing guidelines limit the number of people who can be in a classroom at the same time. Their goal, Yankovich said, is to maximize the large classrooms they have that allow for full sections to be in class together and then find creative ways to offer the remainder of the courses.

“Typically, we fit just about 18 cadets, two to three feet apart (in a classroom),” Col. David Lyle, the vice dean for resources, said. “Well, now we’ve got to move them six to seven feet apart. So, when we do that, obviously, we’re going to have to ask some people to step away and do some things remotely. There are some types of curriculums that are better for that than others.”

About 15% of classes will be taught fully virtually including most English courses and many humanities courses. The remaining 35% of courses will be taught in a hybrid way, to include virtual instruction and some in-person meetings. Classes being taught this way include the General Chemistry II course being taught by James.

The hybrid classes will be taught in two main ways. One method is to have half the class learn remotely while the other half of the class attends in person and then they switch places each time the course is offered. That way, Yankovich said, the professor is seeing each cadet at the minimum every other lesson. This is the method being used in James’ chemistry classes.

The other method takes advantage of the new 70-minute class periods. For the first 30 minutes, half of the class will attend in person while the other half attends remotely. They will then take a 10-minute break in the middle and switch places allowing professors to meet with every cadet in person for part of every class. The second method will be mostly used with math and foreign language classes Yankovich said because in person instruction was deemed to be vital.

“It's not our preferred modality, but we’re doing it to facilitate the fact that we just don’t have enough classroom space to do in person and social distance for everybody,” he said. “I think we’ve made a lot of improvements in the way that we’re going to deliver distance education to kind of make it seamless.”

Unlike the spring semester where they were forced out of the blue to begin remote learning, they have had months to prepare this time. This planning included purchasing new technology such as devices to facilitate classes being taught in a hybrid form and precision writing devices to help cadets and professors interact when not meeting in person. They also learned from the challenges they faced throughout the spring semester and adapted how remote classes will be taught. Instead of trying to teach them as if they are in person, a remote learning working group developed new processes to facilitate learning in the new environment.

The decision was that a traditional lecture method of teaching doesn’t work remotely. Instead, professors were encouraged to record short videos no longer than eight minutes if they need to present new information. The digital class time can then be used for discussions between the cadets and the professor.

“We found that in English classes there tends to be a lot of reading, a lot of writing and a lot of discussing of those writings and reading passages,” Yankovich said. “We think that the reading and the writing, that has to be kind of done on your own, and then the discussion can be facilitated in (Microsoft) Teams in the virtual environment.”

All of the decisions of how to teach classes, including which ones needed to be in person, were made after extensive testing. Professors studied air flow in classrooms to see what would be safe before it was determined that masks and social distancing were the best and safest choices.

Mock classes were also set up to see potential challenges there could be such as auditory issues caused by the masks or the inability to read lips during foreign language classes.

“We mocked classrooms and we said 'OK, how do we do this with masks?'” Lyle said. “Well, it’s really hard to hear people. OK, move to a face shield. A face shield creates more auditory challenges for us. OK, there’s going to be maybe half the kids in the room and half the kids not in the room. How do we do that? Do we just put a camera in the room, and they can watch? Well that’s kind of suboptimal. So, we started piloting things. Our departments have just been phenomenal and coming up with great solutions to some of this stuff.”

Solutions they found include using new technology and adding lapel mics to help amplify the voices of speakers wearing masks. Some courses will also offer in person and virtual sessions allowing for cadets who may get sick during the semester to switch to a remote course if needed.

They have also set up outside areas where professors who teach fully remote classes can host “meet and greet” sessions with the cadets in their classes early in the semester. In all, the planning process was a full-force effort that required them to solve new problems and lay the groundwork to be adaptive as additional ones occur.

Social Sharing