Shortly after I took command of U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM), I received my initial counseling from then-CSA, GEN Mark Milley. He looked me dead in the eye and said, “Mike, you’re responsible for the readiness of our Army.” I sat back in my chair and thought, “Wow…that’s a really big deal!” But, after I thought about it for another minute or two, I realized, “While this is a big deal, we have – and will continue – to get it done.”

When I assumed command, in March 2019, the Army was in a strong readiness posture. This is due, in large part, to my predecessor, GEN Abe Abrams, and the Army Senior Leaders because as a whole, the Army had been surging on readiness for Large Scale Combat Operations for about three solid years.

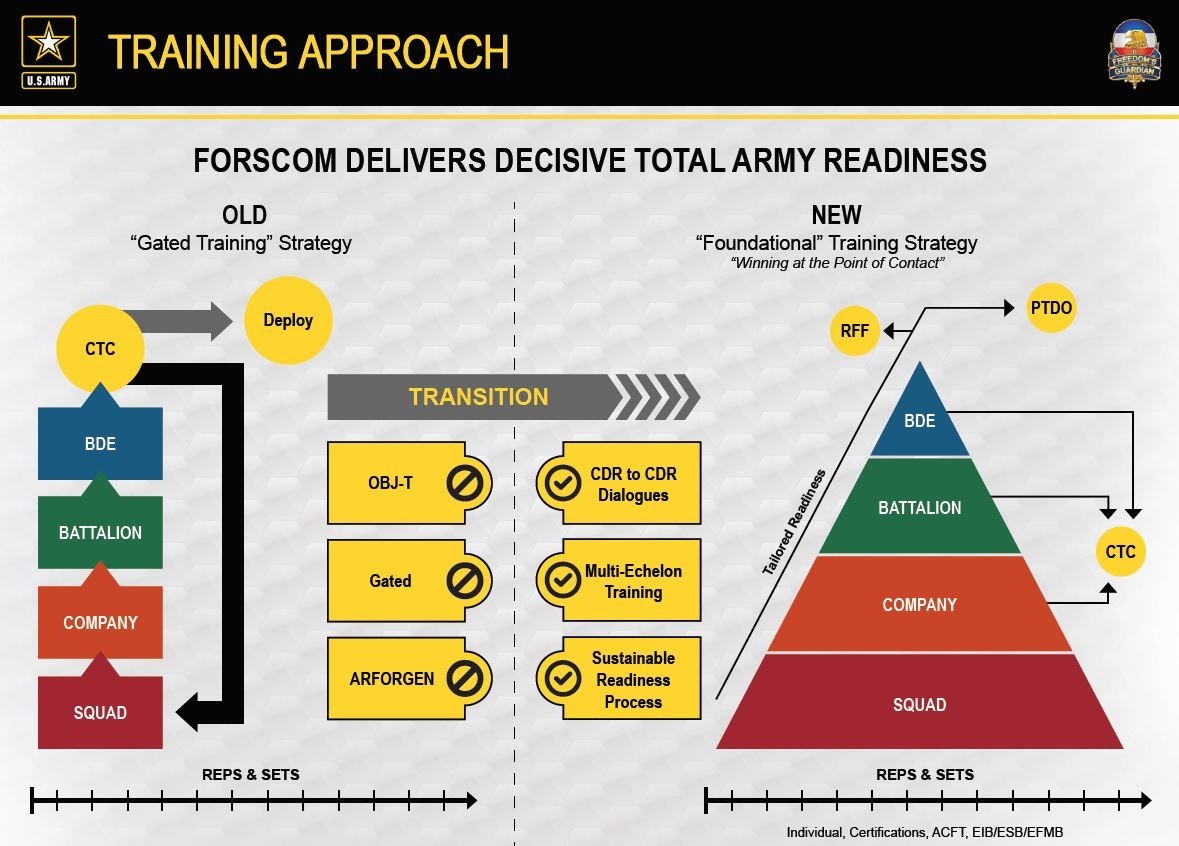

As I conducted my initial commander’s assessment, I traveled across the country engaging our Leaders and Soldiers, and observing training – particularly, rotations at our Combat Training Centers (CTC). It occurred to me that while our battalions and brigades were more ready than they had ever been, at lower echelons, quite frankly we were not as good as I thought we were. The Army’s surge on readiness produced significant gains in our readiness metrics – across all components – and we absolutely needed that focus to produce those gains. However, these readiness levels came at the expense of individual Soldier Skills, and our crews, teams, squads, and platoons. Although generally capable, we were not as proficient with our weapons, equipment, and systems as we could be – we lacked mastery of our warfighting fundamentals.

Brigade Soldiers are taking part in one of the U.S. Army's most challenging land force training exercises and have prepared for entering “The Box” for over a year, including during their 2019 annual training at Fort Hood, Texas, where they completed an eXportable Combat Training Center exercise.

The 1st Combined Arms Battalion, 194th Armor Regiment, is a Minnesota Army National Guard battalion headquartered in Brainerd. The overall unit mission is to provide heavy armor and mechanized infantry ground combat power to the 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 34th Infantry Division. (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Sebastian Nemec) VIEW ORIGINAL

It appeared to me that we had a mismatch between our training strategy, our readiness models, and readiness metrics. The FORSCOM readiness model relied upon a 12-month training strategy. Our brigades, however, found themselves trying to execute their training strategy with only seven to nine months of available time. Intensifying this were the impacts of operational requirements and resource constraints. When it came to training, we had a difficult time meeting the strict, codified requirements for crew qualifications, gunneries, and Live Fire Exercises in accordance with our training strategy – which were already tough – while simultaneously managing continuous personnel turnover within our brigades. As a result, our Armored Brigade Combat Teams had to shoot multiple sustainment gunneries each year, and our Artillery formations were trapped in continuous section certification cycles, which further exacerbated the time challenges in our Brigade Combat Teams. Our Soldiers could shoot, but not necessarily maneuver, which meant they were losing more than they were winning at the point of contact. All of these conditions, when combined, created palpable and unsustainable stress on the force.

Over the course of my 36-year career, the best units I have been in had highly trained crews, squads, and platoons that could win at the point of contact. In other words, when these small teams encountered an obstacle – anticipated or not – they could quickly defeat it and move on the next objective. Winning at the point of contact generates organizational momentum, which permeates throughout the unit. The formations where I experienced this sort of momentum achieved it through disciplined training and high standards on individual and small unit tasks.

Regardless of the location or mission, the Soldiers in our crews, squads, and platoons will be the first to make contact with the enemy, and it is at that point they must decisively prevail. I believe that you can have the best strategy in the world, but if you can’t win at the point of contact, you can’t win – period.

To be clear, the concept of “Winning at the Point of Contact” extends to all of our Warfighting Functions and Military Occupational Specialties, and beyond the Contact Layer. Whether it’s a tank crew acquiring and engaging targets faster than the enemy crew, or a Cyber Operations Specialist neutralizing a web-based threat, or a wheeled vehicle mechanic troubleshooting faults on an MRAP – the expert execution of actions on contact creates organizational momentum.

Winning at the point of contact requires squads and platoons to gain positional advantage by mastering transitions between movement and maneuver. This momentum frees Commanders to drive the operations process, and consolidate gains, which sustains the momentum created.

In other words, momentum creates temporal space where commanders and their staffs are not solely focused on the immediate close fight. They can focus on what is next – on sustaining momentum – on using resources to win the next fight, and the next… rather than resources consumed to “Save the Day.” That temporal space allows them to better integrate and synchronize warfighting capabilities at echelon – shaping the future fight and enabling more wins while preserving combat power.

That is why winning at the Point of contact matters. So, how do we get there? In my FY20 training guidance, I describe a training progression aimed at mastering the fundamentals at the individual, crew, and squad level – and progressing though multiple repetitions and sets, under varying conditions. I call this the “Foundational Training Strategy.” We want to reinforce that we train to standard – not to time. This means commanders must make time for subordinate units to re-train – and do it again until they get it right, and never get it wrong. More than just skill acquisition, mastery is a mindset. It is difficult to achieve, and requires grit, persistence, and determination. Most importantly, it requires time.

Strengthening leader development is something I think a lot about; it is a Freedom 6 priority. Small unit training is one of the best ways to develop leaders – and investment in leader development is essential – especially today as we wrestle with the competing demands for our NCO talent.

That is why I directed commanders to dedicate and protect time each week for what we call “Leaders Time Training.” Now, for many of you, this might sound a lot like the old Sergeant’s Time Training (STT) – and it should. The fact is that over the years, this sort of protected time to focus on the basics became passé, or at least perceived as such. As a result, commanders did not prioritize STT, which led to inconsistent application across the force. I have always believed that by increasing emphasis on individual and small unit skills – and empowering NCOs to execute this training, Soldiers can become masters of the fundamentals, and in turn, those Soldiers will – one day – train their Soldiers to a level of mastery.

Anyone who has been around the Army long enough will tell you that our training strategy is anything but revolutionary. However, since adopting the Foundational Training Strategy last year, we are beginning to see concrete, positive returns on our investment. Our Combat Training Center (CTC) cadre are reporting an increase in successful defense operations at echelon, from orders process planning to defense preparation. Cadre also report that units are entering the 14-day force-on-force period at increased levels of proficiency, which has led to the world-class Opposition Force (OPFOR) being more challenged when faced with Rotational Training Unit (RTU) defenses. Our ability to "close the gap" with OPFOR at the CTCs is a direct result of investing the necessary time for repetitions during home station training.

While these reports are promising, we still have work to do. Commanders at echelon must improve their ability to integrate the full measure of their forces during conflict. For example, units that do not incorporate TOW Missile, Javelin teams, mine plow and rollers, CBRNE, communications, and maintenance find themselves challenged to win at the point of contact against a near peer threat. Commanders need to ensure that their training glide path incorporates a holistic approach while gaining efficiency through multi-echelon training to ensure that critical areas are not overlooked. According to the CTC cadre, small oversights such as these become readily apparent when conflict begins.

Increased reps and sets at the lower echelons result in better trained small units, but as I stated earlier, the foundational approach applies to all Warfighting Functions, and includes staffs. When commanders and staffs commit to the reps and sets, they are more prepared to drive the operations process – and can synchronize operations, while building tactical readiness – generating real options. That is how we master the fundamentals.

People often ask me why I, a four-star Commander, am so focused on our Army’s lowest echelons. Every time, my answer is, “That is where we win… and if you haven’t already heard – Winning Matters.”

Editor's note: General Michael X. Garrett assumed duties as the 23rd Commander of United States Army Forces Command, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on 21 March 2019. As Commander of the United States Army’s largest organization, he commands 215,000 active duty Soldiers, and 190,000 in the U.S. Army Reserve, while providing training and readiness oversight of U.S. Army National Guard. In total, the Forces Command team includes 745,000 Soldiers and 96,000 Civilians. General Garrett has commanded at every level from Company through Army Service Component Command, and led units in combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Social Sharing