Flexibility is a word not just used to describe the dexterity of a gymnast or a highly-skilled athlete, it also pertains to the mental swiftness and ability to overcome the circumstances of an ever-changing environment that may pose many difficulties for ultimate success.

As the stress of COVID-19 continued to ravage the world during the spring, it also played a role in ruining the initial Cadet Summer Training schedule. The U.S. Military Academy’s Department of Military Instruction generally spends about seven months working and fine tuning to its final means for the cadets to accomplish their Army training tasks through the months of May into August.

However, a planning team of 10 DMI instructors, led by Lt. Col. Adam Sawyer, the chief of DMI’s Military Science and Training, had to scrap and redevelop their original summer training plan in three weeks during late April and May. Within the plan, what generally takes more than three months over the course of the summer to execute is now consolidated into a six-week training timeframe. The new timeframe includes the return of all the cadets and new cadets under an added 14-day controlled monitoring period for COVID-19 for Cadet Basic Training, Cadet Field Training, the new Cadet Leader Development aimed at the firsties, Cadet Candidate Basic Training and Air Assault training. Cadet Leader Development Training was canceled from CST Tuesday.

Sawyer said the preparation within the seven-month process involves synching everything from the actual training schedule to chaplain’s time and the dean’s requirements to submitting the request for the task force and supplemental units who help lead and train the cadet cadre and cadets. But the execution for possible changes began in March with a campaign plan submitted to the superintendent, Lt. Gen. Darryl A. Williams.

“As we came out of the planning team, we had a primary course of action and then we had two branch plans,” Sawyer said. “The way it works is you have a primary course of action and if you hit a decision point, and you say you can’t do this at a decision point, then you go to branch plan one.”

Sawyer said they developed a regular summer training plan, then they had to redo it and have a new primary course of action—which they did.

“We completely replanned branch plan one and synchronized that piece, so what we’re executing here is our branch plan one for summer training. Each time, we totally went through and resynched it, replanned it,” Sawyer said.

In the end, Sawyer said the plan was tweaked four times, but one of the toughest parts of the continuous changes was always trying to keep not only the task force of 3rd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division in the loop, but also the other CST support units and agencies abreast of the fluid schedule situation.

“The hard part is how do we rapidly communicate this to everyone involved,” Sawyer said. “Everyone involved here at West Point and everyone involved in the task force units … and how do we rapidly get feedback from everyone to validate what our planning is and our plan, that is the challenging part. We can very quickly come and put (a plan) together, but it’s between the internal and external—about 25-to-30 agencies – that have some type of say in this that we had to get feedback from, which again is the hard part.”

With that in mind, being flexible is the key to make everything work, and Sawyer said his whole career has been about flexibility.

“Twenty years of leading troops … it’s in my DNA,” he said, including a time he took over his injured battalion commander and commanded his unit for six months in Afghanistan. “The one thing I am very familiar with is flexibility. This (CST training changes) just further enforced it.”

Preserving the Summer Training model

Many hard decisions were made to best maintain the summer training model, which now shoehorned three-plus months of training into a six-week tight fit. Sawyer said he and DMI-6’s (DMI director Col. Alan Boyer) biggest decision was to preserve the USMA summer training model going forward. Sawyer did not want the cadets to go out to train for the sake of training and destroy the model for the next two-to-three years.

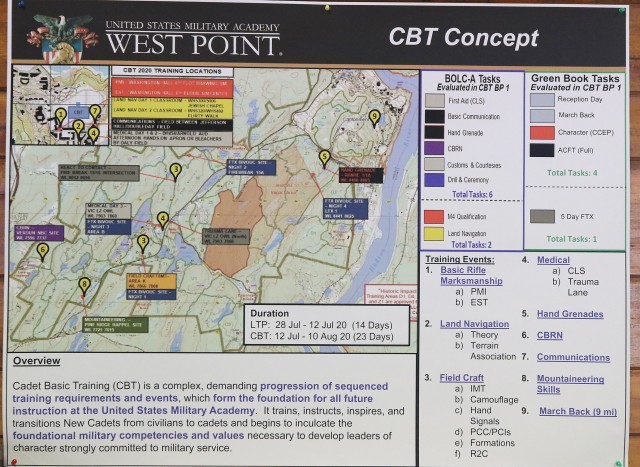

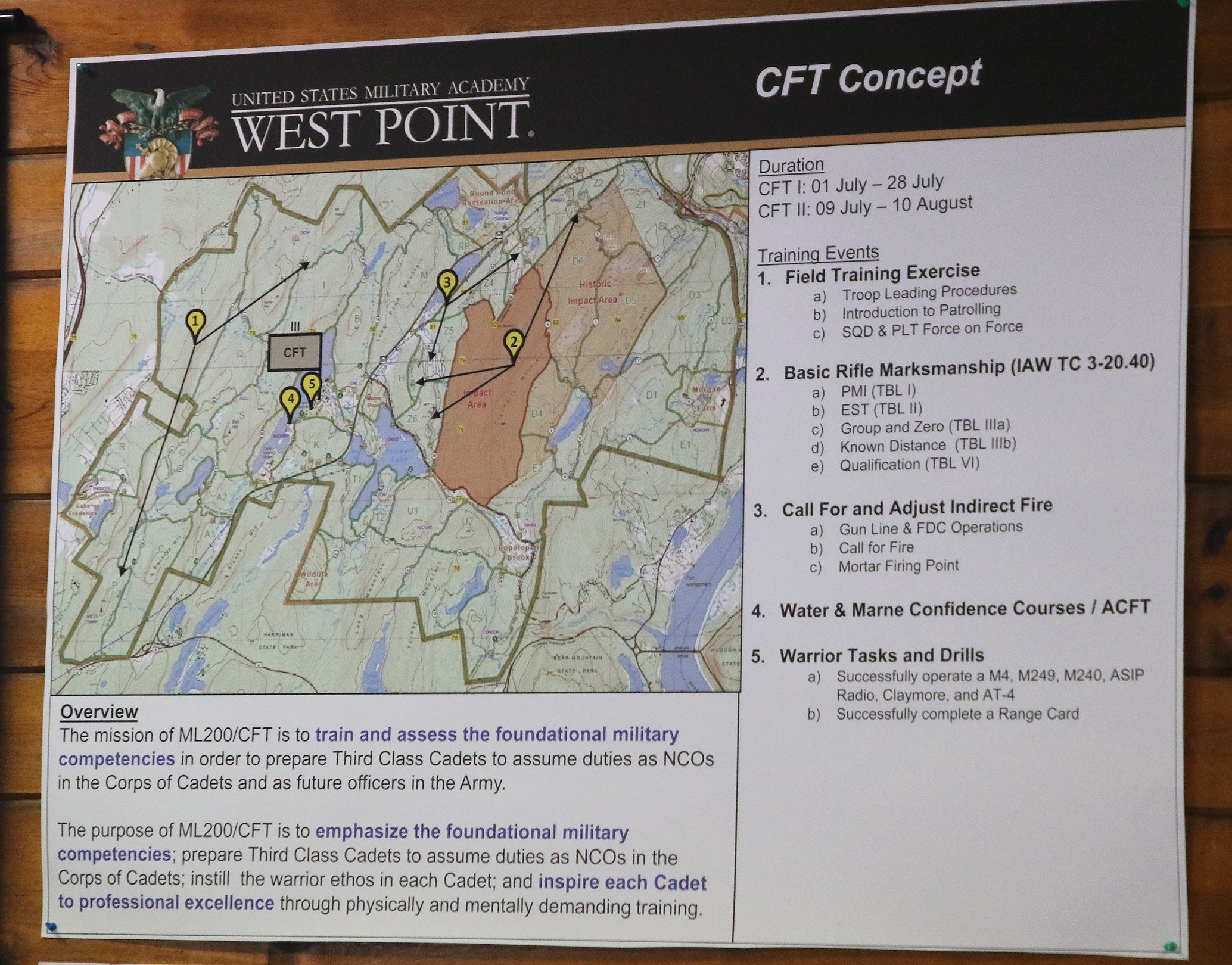

“The decisions we made, the two biggest were, first and foremost, we had to bring in the Class of 2024, if there is anything we have to do this summer it is bring them in,” Sawyer said. “Number two, when you look at what we produce and our model with (Basic Officer Leader Course) A tasks, those are the tasks that the Army says cadets have to do to become lieutenants. We finish our model with them after CFT. What does that do? That enables them to do additional, enhanced training in their junior and senior years—they are able to go to the Army for Cadet Troop Leader Training, they are able to do CLDT, which is really our West Point capstone training event.

“We looked at it and said, if we want to preserve our model, we have got to focus our efforts on CFT and finishing the BOLC A tasks,” Sawyer added. “Then, with CLDT, it’s not an Army requirement, it’s a West Point requirement, but the cadets say it is the most important training they do—it’s like a mini Ranger School. Typically, 900 seniors and 200 cows (juniors) take part and then those 200 cows serve as cadre the following year—it provides some flexibility. We had planned to execute a reduced CLDT for 200 cows but decided for greater flexibility not to (as it was canceled Tuesday) and focus on CFT and CBT.”

For example in terms of the model, with CBT, Sawyer said due to the training being limited to four weeks, even though land navigation and basic rifle marksmanship are BOLC A task requirements, they will not do them this year because they can be pushed to CFT next year because it is something both CBT and CFT cadets do in a normal CST schedule.

“No one wants to cut out land navigation, but the reality is we were forced to make some hard decisions on what we are training,” Sawyer said. “We looked at any repetitive BOLC A tasks like land nav, and they will get exposure to it and get taught the basics on how to use a map and everything, but actually going out in the woods and doing it, we won’t be able to do that—but that’s OK, they will do it next year and we will focus on it then.”

New challenges ahead and innovative ideas in a COVID-19 environment

A big challenge facing training this summer is what does that look like in a COVID-19 environment and how could it be developed? To help answer the question, Sawyer traveled to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, under the superintendent’s directive, to understand how the Army was training initial entry trainees and how to model that for CST.

The idea of the 14-day controlled monitoring period came from what the Army was doing with its initial entry Soldiers.

“We are mirroring, mimicking what the Army does … what I observed at Fort Jackson with the basic training Soldiers, we’re doing the same thing with our cadets,” Sawyer said. “We are not doing training during controlled monitoring where you have people on top of each other like marksmanship where instructors are right on top of you. We are doing training that is low resource and low instructor required.

“Then we will keep them in platoons of 40—that’s your fire break—and they will live, eat and breathe in a platoon of 40,” Sawyer added. “It’s a fire break because if for some reason someone becomes symptomatic, now we have prevented it from spreading. That also means when you develop the training plan, you do a lot of low resource stuff up front and then once you get past your two weeks of controlled monitoring, then you can open the aperture up (for training).”

And what basic changes should cadets expect or be expected to apply to make themselves and everyone around them safe? What Sawyer explained is that from his Fort Jackson experience, if cadets do three things: wear a mask, social distance as much as possible and constantly sanitize their equipment and their hands, that those three things would, “be 75-to-80% helping the fight, and if they are doing those three things, they are going to mitigate risk. However, there is always going to be potential vectors of how you can get contamination.”

Sawyer also said expect physical training to look a little different with formations spread out more during runs to include no cadence. Also, when it came to doing pull-ups, which is a part of the new Army Combat Fitness Test, cadets could wear gloves, or not wear gloves but sanitize the pull-up bar after each use or use a contraption that connects the cadets to the pull-bar without touching it.

“Things will look different, but the intent is we are still running and still doing physical activity,” Sawyer said.

High praise for the team and the ability to keep up the world-class training

Sawyer has high praise for his DMI team and the work they did to help in the process of CST planning. Piecing together a matrix that didn’t convolute things where groups from CBT and CFT, for instance, would find themselves at the same training area trying to use similar ranges was an indication of how well the planning team worked in getting the job done under atypical circumstances.

“I’m blessed with a great team that is extremely cohesive and they are high performers,” he said. “They communicated well, and the hard part was they had to do this via (Microsoft) Teams because it wasn’t like we were coming in meeting face-to-face. It’s a testament to what a cohesive team can accomplish.”

Two members of the team, Capt. Griffin Spencer, CFT S-3 operations officer, and Maj. Ryan Hintz, CBT S-3 operations officer, were deep in the process of making sure the cadets are getting the training they need to achieve their graduation requirements.

“We are responsible for teaching and educating the Army to our plebe cadets,” Hintz, who is the Military Science 100 (Plebes) course director during the academic year, said. “I receive them on R-Day and I hand them off at the conclusion of their plebe year. We lay the foundation that hopefully gets built upon through all their MS and summer training experiences.”

Spencer believes the cadets in CFT will ‘absolutely’ get the best training, world-class training as Sawyer calls it, despite the cuts and training changes made this year.

“While we omitted some events, what that allows us to do now is make priority the core events which comprise their evaluations— we’ve done away with all the events that don’t correspond with a grade,” Spencer said. “But, what that allows us to do now is spend more quality time on those tasks and focus a little bit more on core-evaluating events. I see it only as a positive to allow us to focus on quality and making sure these core assessments/events receive the attention they need.”

One final piece to CBT, Hintz said, is the initial course of action was to have three weeks of CBT, but the commandant, Brig. Gen. Curtis A. Buzzard, was pushing to find a way to add a fourth week to concentrate on standards and discipline.

“The guidance we were given was use that time to focus on standards, discipline and character development,” Hintz said. “You can say they will have two fewer weeks of training (from the original six), but I can tell you that when they transition to Reorgy Week and fall into their academic year companies, they are going to be better prepared to be members of the Corps of Cadets when they finish CBT.”

Social Sharing