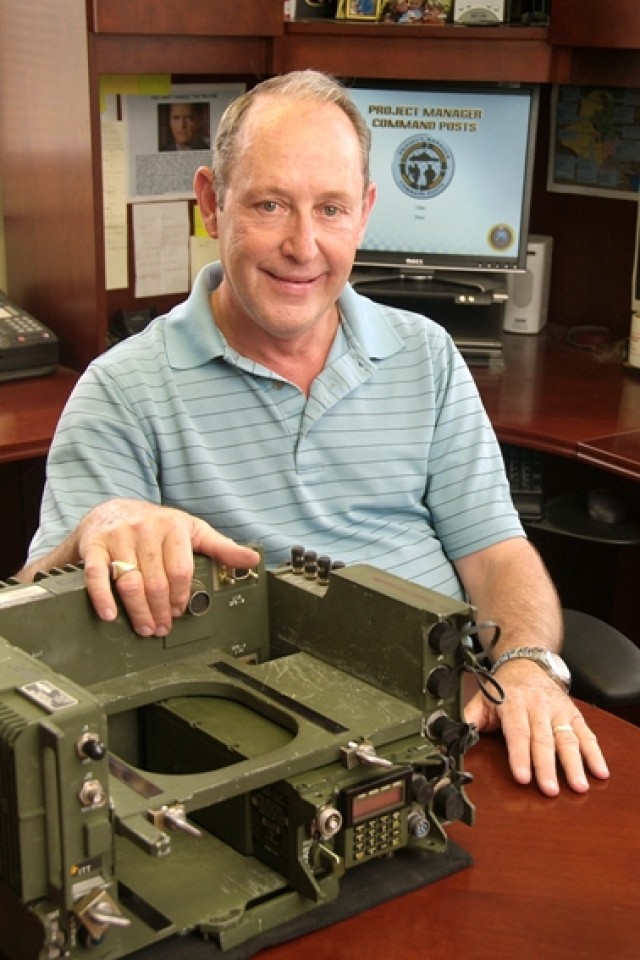

FORT MONMOUTH, N.J. -- As he approaches nearly 40 years of government service, James G. Bowden's career has been tightly interwoven with the development and evolution of an Army "workhorse" that is notable within the Department of Defense.

Bowden is the Army's technical lead for the Single-Channel Ground and Airborne Radio System (SINC-GARS) family of radios, a versatile and ubiquitous product that has been in every combat action since 1988.

In his oversight role of SINCGARS over 20 years, Bowden has seen a steady march of product en-hancements, a steep ramp-up of production, a relatively flat cost structure and a continuous drive for new capabilities.

"SINCGARS is the highest volume electronics production program in the Department of Defense-and has been for a long time," said Bowden, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the radio is reminiscent of a high school coach who knows every trophy and victory his team has earned.

With its Very High Frequency (VHF) band-the most robust band for voice communications-SINCGARS remains the main voice control radio for Soldiers at battalion level and below.

"Voice is what the commander wants on the battlefield," Bowden states in his authoritative tone.

"Data is well and good for planning purposes, but when the fight starts commanders use voice. Com-manders like to hear the stress in their troops' voices when they are talking to them because it tells them a lot about what's going on with the battle. And you can't get that feeling from data, so they will never give up voice. Voice will always be there, regardless of anything else that happens."

Using SINCGARS, with its secure, jam-resistant, tactical communications for voice, data and video, commanders have the ability to absorb various aspects of battle. The radios are available for manpack, airborne and vehicular use.

The radio's longevity is due to a software-based design along with an extremely flexible and adaptable plug-in architecture. Those factors have allowed SINCGARS to grow and anticipate the Army's communications needs.

SINCGARS development is done under the Army's Project Manager Command Post, Product Director Tactical Radio Communications System (PD TRCS). That organization is under the Program Executive Office Command, Control and Communications Tactical (PEO C3T) located at Fort Monmouth.

"It's loved by the troops," Bowden said of SINCGARS. "They are extremely reliable. And that's part of what the troops love about them. They know that when they turn them on they're going to work."

Over the years that Bowden has shepherded SINCGARS, one of the highlights was a significant ramp-up of production arising from Army operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. In a war like Iraq with no defined front lines, communications is vital even at the level of a single vehicle. The Army decided that the authorized level of SINCGARS should increase from about 250,000-260,000 radios to 581,000.

"Within a six-month period, production ramped up from about 600 a month to about 6,000 and has been at 5,000 to 6,000 radios since then up to today," Bowden said. "We have produced about a quarter million radios in the last three to four years."

In reviewing the history of SINCGARS, Bowden said an early, head-to-head competition between two manufacturers placed the program on solid footing in containing costs, as well as a cycle of perpetual enhancements.

In addition, cost savings were fed back into product improvement, Bowden said, but another critical factor in the program's success was maintaining a focused and disciplined approach to how SINCGARS evolved. He also credits a strong government/industry partnership and an outstanding staff.

"As we did each of the enhancements, we took it in manageable chunks," Bowden said. "Costs can get out of control, particularly if people are coming up with new ideas in the middle of it. So as long as you control those implementations over time, and you do it in manageable chunks, you keep program costs down."

How does one determine what is or isn't manageable'

"You have to tighten the appetite. That's really what it amounts to," Bowden said. "You have to make a decision on what the basic functionalities are, and it's not easy. You can't take a tank and expect it to swim. You have to keep things under control. And it's hard; it's really hard because commanders will see new products and say, 'Wow, if I have this I can do this, and I can do this other thing, too.' "

Bowden sees his role as someone who has to provide the bigger picture. When "appetites" seem to be growing, Bowden will say, "Well, yeah, but which one of those do you really need right now'"

"That's really what it boils down to," Bowden continued. "You really have to fixate on the basic functionality you want--and get that built. Once you have that built, then you can start adding all the bells and whistles."

Although Bowden on occasion may have to tamp down expectations, he generally isn't perceived as a technical spoilsport.

"You explain to them, 'Look, we could do that but it's going to take you twice as long and twice as much. We can get there, but if we do this first, you'll get this capability now within the budget that we have.'

"I've also had very good support from senior management in the Army and in industry for all these years. When we've seen something that we felt we needed to improve the radio, I've always had that support behind me to make that happen. And we have significantly changed the capabilities of this radio over the years."

Since about 1989 when SINCGARS first entered production, the radio is much stronger, better and much more capable, Bowden said. "There's no comparison between the capabilities of the radio today and then."

With several models of the radio within quick reach from a nearby shelf in his office, Bowden can me-thodically recite with precision and clarity the history and evolution of the radio. It's nuclear-hardened. It can withstand temperatures ranging from minus 51 to 70 degrees centigrade. It's widely used by the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.

Looking out into the future, the Army plan is to have 488,000 SINCGARS radios in its inventory by 2028.

"I have 38 years [of government service] in June, so I'm not going to be around in 2028," Bowden says.

"I would like to stick with the program until we finish the 2013 fielding. At least in my current job, I'll be here through 2011. After that I'll try to find some way to stay associated with the program, but probably not in the same capacity."

What advice would he give his successor'

Upon hearing the question, Bowden immediately erupts into multi-calorie-burning laughter, and manages to say "a lot of valium" as he continues to laugh.

"We've been trying to find someone and it's been hard," he said. "It's hard to find someone who has the experience to tie it all together. SINCGARS is a very complicated program. We touch a multitude of pro-grams. It's one of the most critical technologies."

As a reprieve of sorts from the realm of acronyms and techno-speak associated with military radios, Bowden turns to golf. Various golf-related items populate his office.

The game, he says, plays an important part in his life. "Sanity," he says with a good-natured laugh. "Not that you'll get any sanity out of playing golf. That's the only exercise I get."

Despite the complexity of the SINCGARS program and all its potential extensions, Bowden said his overall experiences have been good.

"There's nothing like being a project leader," he said. "It's very rewarding.

"I don't know too many people who can say they put half a million radios into the field. In the time I've worked in SINCGARS, we've put that many out there. You know that you're saving lives of troops every day out there and that's rewarding.

"It's exciting. We're always coming up with something new."

(This article appeared in Spectra, the magazine of the CECOM Life Cycle Management Command. To access the full issue in PDF format, 3.2 megabytes, click on the link appearing in the Aca,!A"Related LinksAca,!A? box at the start of the article.)

Social Sharing