Between 2000 and 2013, there were on average about 80 active shooter casualties per year. From 2014 to 2017, that number increased by 366 percent to an average of 293 casualties per year. The likelihood that you or somebody you know will experience an active shooter situation continues to rise.

A new software technology developed by engineers with the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (CCDC) Armaments Center would, when ultimately deployed, use existing emergency infrastructure that could disrupt a shooter’s plans, increase situational awareness for victims and responders, and potentially save lives.

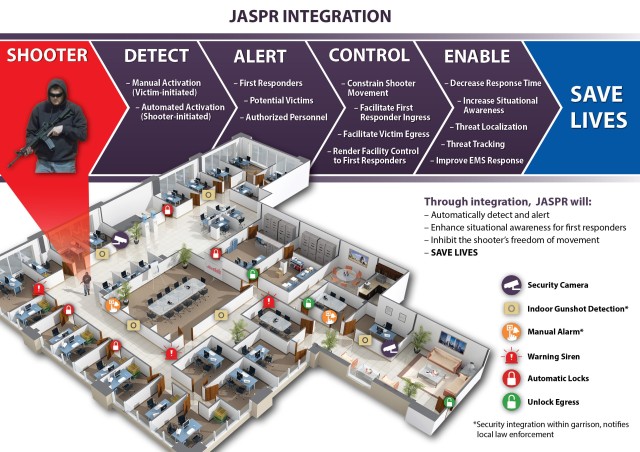

The Joint Active Shooter Protection and Response System, also known as JASPR, is the first modernized active shooter mitigation capability designed to instantly detect, alert, control and enable first responders and increase the chances of survival in an active shooter scenario.

The vision behind JASPR is that its sensors would eventually be as common in buildings as smoke detectors, fire extinguishers, fire alarms, and sprinklers are today.

How it works

When a shooter enters a building, the first shot fired would be detected by a gunshot sensor. A second modality for detection is a manual push button/pull lever that acts very much like a fire alarm would.

Notification is then set to alert emergency responders, much like a fire alarm would. Depending on the configuration set up in the building, alarms could sound, warning messages could be displayed on marquees, and or door locks could limit the shooter’s mobility.

Cameras can track the shooter’s movement and send live feeds to smartphones used by first responders. By providing law enforcement with more information, it takes situational control away from the shooter.

“With JASPR, 911 is now confirmation, not information.”

Those words echoed by Lt. Col. Charles Ergenbright reverberated throughout the United States Military Academy Preparatory School auditorium at West Point, New York, several times over the course of a recent two-day technology demonstration for the JASPR prototype.

JASPR is the product of a thesis that Ergenbright wrote more than a decade ago while attending Naval Post Graduate School, in hopes of finding a way to combat active shooter scenarios and reduce response time should an incident occur. The objective of the demonstration at West Point was to inform select audiences and influencers on the JASPR life-saving capabilities.

Several years ago, Ergenbright’s work found its way into the hands of Andrew Dondero, a computer engineer at Armaments Center. Dondero and a team of engineers were fascinated by his research and were able to secure enough funding from the Physical Security Enterprise Analysis Group (PSEAG) to get started on developing software that would integrate sensors to automatically detect indoor gunshots. PSEAG is DoD’s premier physical security research, development, test, and evaluation innovator.

Through the use of several cooperative research and development agreements, multiple commercial off the shelf technologies were implemented into JASPR’s demonstration at West Point.

In the course of developing JASPR, Dondero said his team spent considerable time studying after action reports from several active shootings including Fort Hood, Washington Navy Yard, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida and others.

“We looked at what the common problems were in relation to Chuck’s (Ergenbright) thesis and what is available now, what commercial off-the-shelf solutions are available now, what government solutions are available now, and how we can tie them all together into one system that starts to attack this problem,” Dondero said.

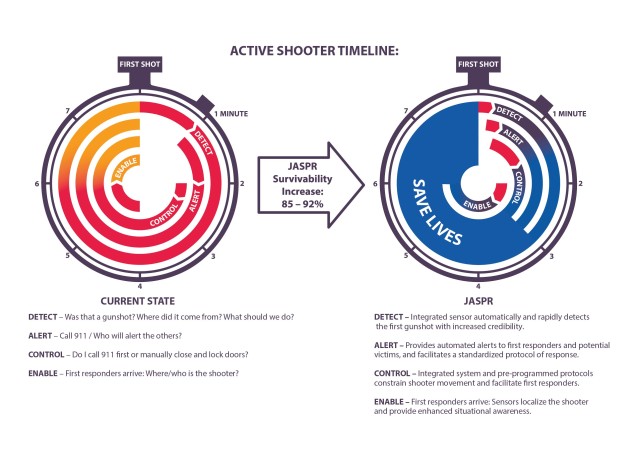

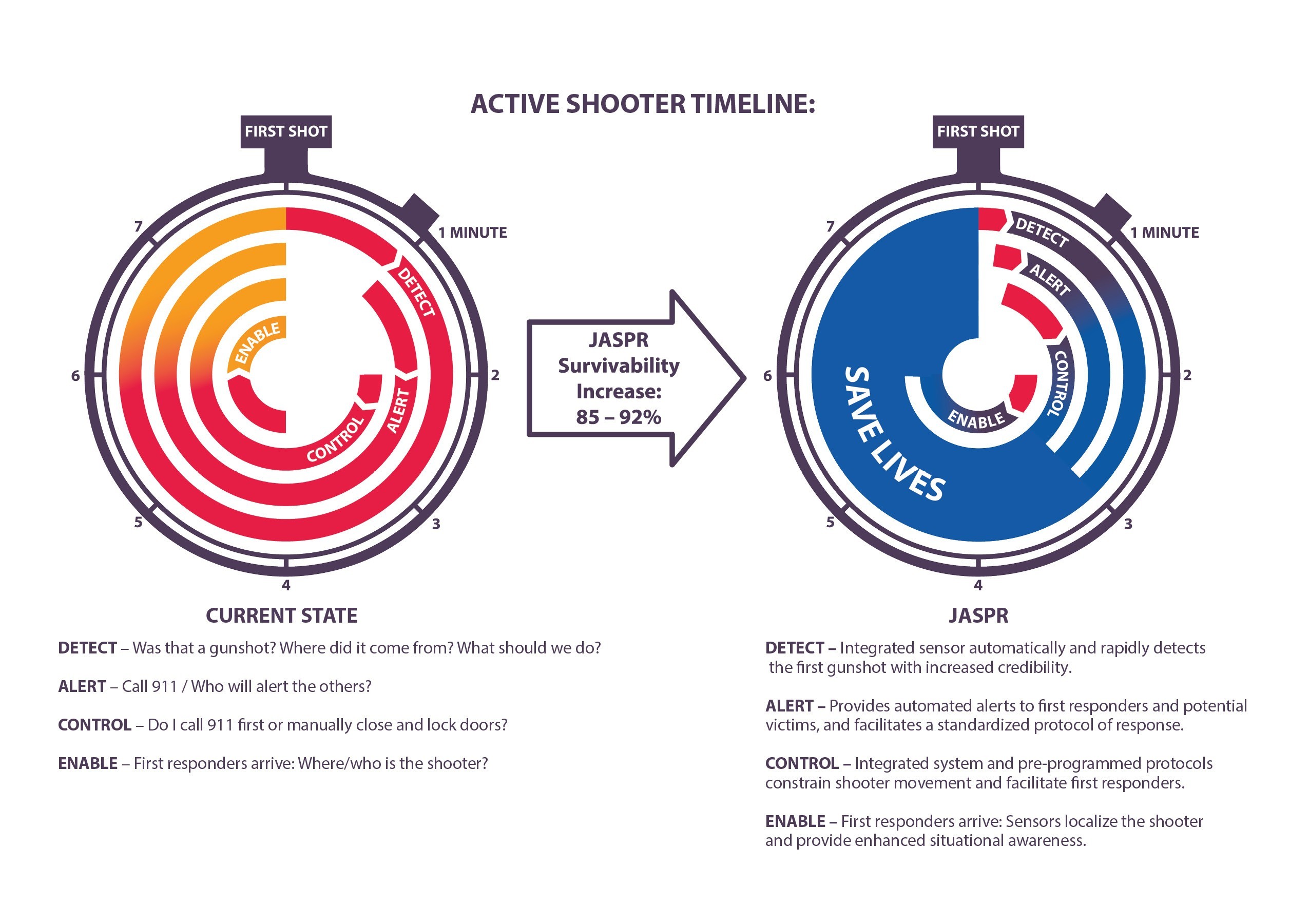

Depending on the location, it can currently take several minutes for any notification of a shooting to reach law enforcement officials. When the study was conducted, the average active shooter incident lasted about 12 and a half minutes. The average law enforcement response time was 18 minutes. Ergenbright states that those numbers have slightly improved in recent years, but that there is still work to be done.

Harrowing audio and video from real life active shooter encounters were used during the West Point demonstration. The April 16, 2007 shooting at Virginia Tech lasted 11 minutes and left 33 people dead, an average of three lives lost per minute. It is the deadliest school shooting in the history of the United States.

As humans we are not programmed to immediately know how to respond, and we may not be able to say with high certainty that we know what we heard, or where we are at. Those factors further delay response time.

Was that a gunshot I just heard? Where did it come from? What should we do? Do we call 911?

JASPR can automatically detect and alert so that when those 911 calls start to come in, they are now “confirmation, not information.’

JASPR enhances situational awareness for first responders and could help save lives. According to statistics provided at the demonstration, “JASPR can increase survivability by 85 percent to 92 percent during an active shooter event, compared to 28 percent with current existing technology.”

With JASPR, the possibilities to are limitless, according to JASPR developers. The customer can integrate as many or as few of these sensors as they desire throughout the building(s) they seek to protect. Mass warning notifications, automated dispatch integration, audio/visual notification and alarm, shooter deterrent systems and automated door locks, as well as auditory instructions or announcements, are features that were demonstrated at West Point.

Lisa Wright, JASPR Lead, U.S. Army Office of the Provost Marshal General at the Pentagon, stated that one of the end goals of the program is to have a product that is available and useful for all.

“Whatever we develop at the government level, has to be interoperable with and joint (all services),” Wright said. “Any service needs to be able to pull it down and use it.

The team compared the process in outfitting schools and places of employment with JASPR to that of the implementation of the national fire code.

“Prior to 1946, there were roughly 10,000 fire related casualties in the United States, in high occupancy facilities,” Ergenbright stated. “President Truman appointed a presidential convention for fire prevention. He appointed an Army one-star general in charge of that meeting, and that was the beginning of our current fire code. Several years later, in 1958, St. Mary’s Catholic School burned to the ground, killing 96 students and nuns.

“With that public outcry, that was the catalyst to fully employ the fire code. We looked at this as a case student because it is an absolute. From 1958 to present day there have been zero casualties in high occupancy buildings that had implemented the fire code. It is very rare in research that you find an absolute. That was an absolute hard problem with a 100 percent solution.”

Ergenbright continued to drive the point home.

“We’ve got fire beacons, fire extinguishers, and a fire alarm right there,” said to the audience inside the auditorium at the Preparatory School. “You don’t have to look far to see fire mitigation measures that decrease response time for fire. But, there’s simply nothing out there for the active shooter problem.”

“We don’t argue that we can prevent it, but we do argue that we can mitigate it effectively,” Ergenbright continued. The second absolute that we found in our study is that a locked door stopped the advance of an active shooter 100 percent of the time. Our focus began to shift to placing a locked door between an active shooter and a potential victim.”

Dondero said that the JASPR system can lock down specific areas of a building, an entire facility, or even multiple facilities if need be.

In order to work with current fire codes, the door locks are ingress not egress, meaning that if victims need to run they can get out and leave.

“Not only is it important to separate the shooter from the potential victims, but it also plays a part in the psychology of what the shooter is doing,” Dondero said. “He’s got a plan, he’s moving through a building, but now he hits a locked door. He’s got to change everything he is doing. It will disrupt him, give us time, and potentially save lives.”

Way forward

Funding provided for JASPR by PSEAG was for a two-year prototype effort that concluded with the demonstration at West Point. The team is currently seeking funding to run an extended pilot at a DoD facility which would increase the Technology Readiness Level as well as cyber-harden JASPR through the Army’s Risk Management Framework process.

Social Sharing