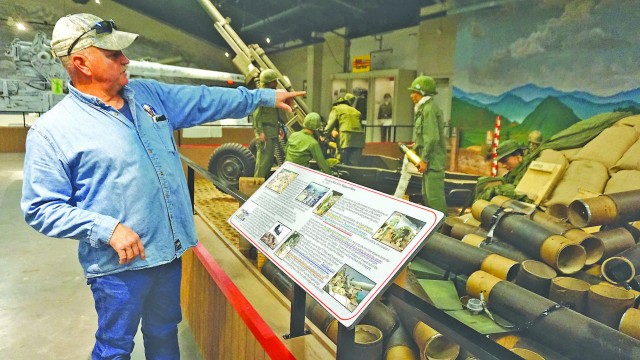

FORT SILL, Okla., March 12, 2020 -- An ambitious diorama showing how field artillerymen operated during the Vietnam War is the latest addition to the new central gallery of the Army Artillery Museum at Fort Sill.

When the gallery will open its doors to the public is anybody's guess, but inside, museum staff and volunteers continue to assemble new exhibits one by one.

"This diorama is intended to show a tiny slice of a Vietnam War fire support base," Museum Director Gordon Blaker said of their most recent accomplishment.

It was built to honor the service of veterans who heroically defended fire support bases in Vietnam, but Blaker cautions them that "this is NOT your firebase."

During the 10 years that the United States had ground forces in Vietnam there were hundreds of firebases and other artillery unit locations. No two were alike. Artillery units usually had an engineer unit along to help them design and construct their firebases.

'IMAGINARY' FIREBASE

"This is an imaginary firebase probably on a cool day in the Central Highlands about 1968. It was built based on a study of numerous photographs and advice from Vietnam veterans," Blaker said.

The exhibit contains two artillery pieces. One is a towed M102 howitzer with a center-mounted base plate that allowed crews to spin it 360 degrees very quickly. Blaker said this was very important in Vietnam, because that was the first American war that had no front lines. An artillery unit might need to fire in one direction one minute and in the opposite direction the next. The M102 saw service in Operation Desert Storm and was replaced by the M119 shortly thereafter.

Mannequins portray the gun crew. The chief is checking powder bags to make sure he has the right charge. Excess powder goes into a burn pit, also part of the diorama, as other crewmembers get the next round ready to go.

The diorama's other piece is a massive M107 175mm Self-Propelled Gun. It had the longest range of any NATO artillery piece at the time -- 20 miles -- but it was not very accurate at longer ranges. Another drawback was that it could fire only about 400 rounds before the tube had to be replaced.

By the late 1970s all M107s would be converted to M110 Eight-Inch Howitzers, which had been introduced in 1963. The accuracy of these guns was legendary, and they would continue to serve the Army and Marine Corps in three models for over 30 years. One of the later M110s is in Fort Sill's Artillery Park.

Firebases were normally located atop hills and mountains so that artillery units could fire in any direction. Soldiers would fashion a circular pit and place the artillery piece in the center of it. Often associated with the pits were bunkers made from tinhorns. These served as crew shelters and a storage area for ammunition.

USED AS DECOYS

Early in the war, the North Vietnamese Army, and Viet Cong forces often attacked firebases, as they made for ideal targets. Eventually U.S. forces turned this to their advantage by decoying enemy units into attacking firebases. They had several ways to detect approaching forces and could inflict large casualties with fewer American losses.

Key people who worked on the diorama include Exhibits Specialist Zane Mohler and the following volunteers: Marine Staff Sgt. Jaycob Turner, Steven Burns, graphic artist Rod Roadruck, and two Vietnam veterans, Jim Hayes and Lynden Couvillion.

Mohler played the part of the wartime engineer who worked with artillery units to tailor each firebase to its geographic location and the artillery piece to be used.

Where they would have scraped off the top of a mountain and marked off where they wanted their perimeter and bunkers to be, "we kind of designed it into our space," Mohler explained. "There's a little bit of everything in all firebases that are displayed in here."

The hardest part of building the display was moving in vehicles that don't run. That was the case with the 31-ton M107. The engine had been removed, but it still had its wheels, so a Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical Truck (HEMTT) was used to drag it into the building. The turning radius of the HEMTT was such that it could not move the M107 inside the building, so Mohler used a forklift and built some 16,000-pound carts that he could put the M107 on to push it sideways.

"Once I got it into the position where we were wanting it, then it was lifting it up so we could put ramps underneath," Mohler said.

The diorama extends 25 feet out from the wall, which has a backdrop 52 feet wide by 12 feet tall painted by husband-and-wife muralists Liz Mercer and Erik Sunderman of Oklahoma City just before the 2018 Labor Day weekend.

Mohler said it took a little over a year to complete the diorama itself. At the beginning he had two Soldiers to help him. Once that arrangement went away, it was up to himself and a team of museum volunteers to do the rest.

"They helped quite a bit with the terrain painting and the terrain features," he said.

MAKING DIRT

Steven Burns, a veteran of the Pershing missile era, was part of that effort.

"When I took over, the first thing Gordon put me on was making dirt," Burns said.

How do you make dirt for a museum display?

"Well, you take sawdust and you take red, black, and brown paint, and you mix it all up, and that's what went under the PSP for the 105mm howitzer there," Burns replied.

PSP stands for pressure-stamped panels, Mohler said. The floor of the imaginary firebase is PSP, which was mainly used to lay runways in the sand on Pacific islands during World War II. It was put to other uses in the Korean and Vietnam wars and is still being used today.

Burns put his artificial dirt down on plywood using a drywall compound to keep it from blowing around. The footprints in the dirt are here to stay. He used a pair of Vietnam-era Army boots to make them. Cooking spray on the bottom of the boots kept the compound from sticking to the boots' grooves. To make features of the terrain he used Styrofoam and whatever else he could find. Even the weeds are authentic.

Social Sharing