For those without a lot of joint or multinational experience in a NATO environment, the Joint Logistics Support Group (JLSG) can seem foreign. Even for those who do have experience in those environments, the situation is much the same. The JLSG concept has been around since 2010, but is fairly new to many logisticians, both U.S. and otherwise. In addition, the JLSG has been employed very little in real-world scenarios, which leads many to wonder what exactly it is, how it can be employed, and how effective it can be. As an Observer, Trainer, Tracker, Mentor (OTTM) at Combined Joint Staff Exercise 19 (CJSE-19) in Sweden, I experienced firsthand one way the JLSG can be used and some of the challenges it faced in a joint and multinational environment.

WHAT IS JLSG?

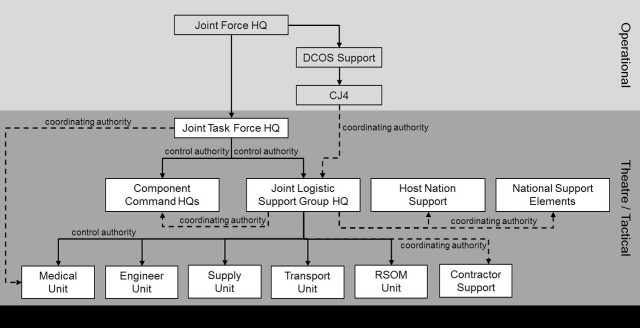

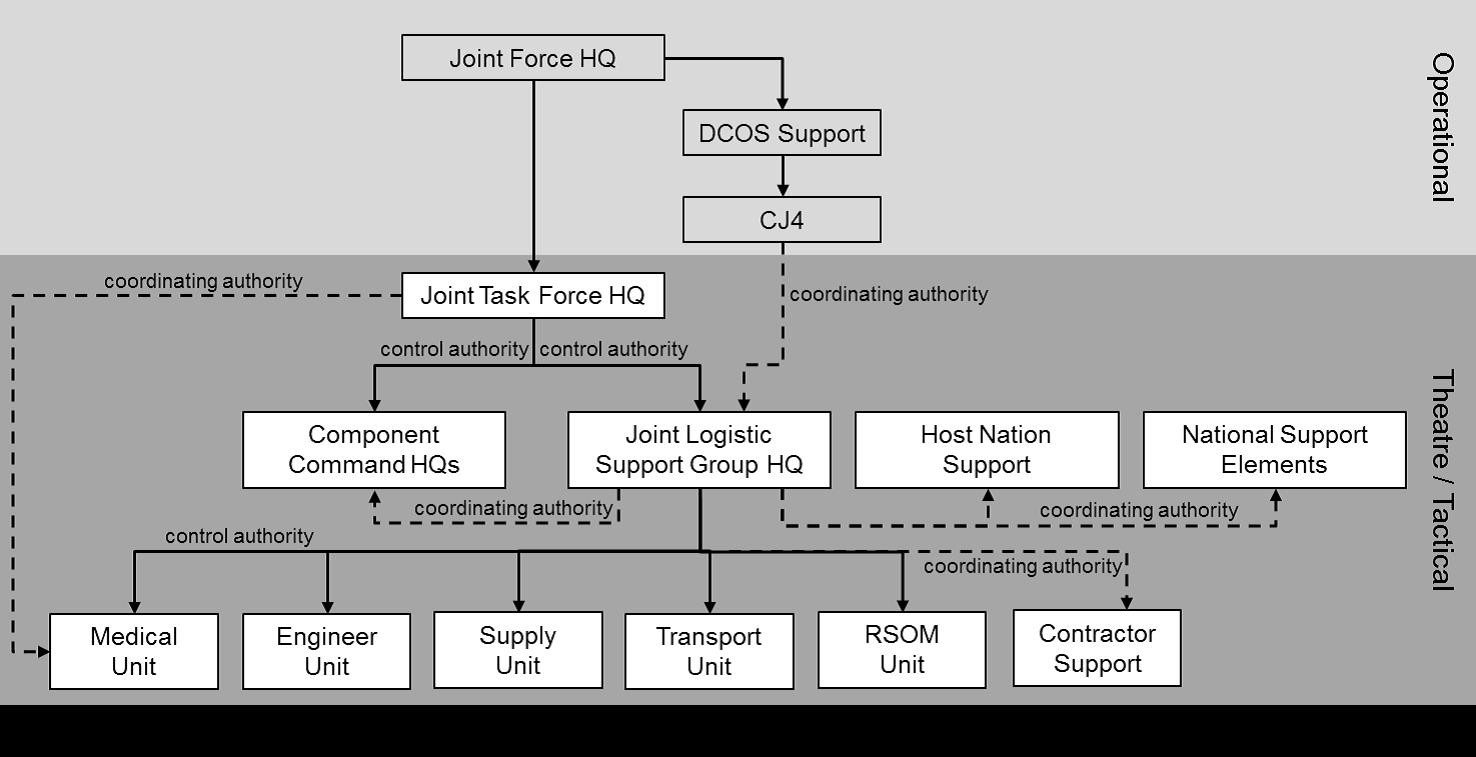

Allied Joint Publication-4.6, the NATO doctrine which covers the JLSG, provides joint commanders and staffs with a common framework for the command, responsibilities, and coordination of the JLSG. The doctrine is not overly prescriptive and admits that differences in operations will force the structure and use of the JLSG to be flexible. AJP-4.6 defines the JLSG as a joint, force generated, deployable logistic capability that provides command and control of assigned logistical forces from the theater to tactical levels in support of a joint task force (JTF) made up of NATO members, partners, and non-NATO nations.

In most cases, the JLSG supports the component commands by providing common services and support to meet their requirements through the use of a combination of its assigned forces, host-nation support, and contracts. In addition, the JLSG is capable of supporting deployment, operational-level sustainment, and redeployment of the force. In essence, and from a completely U.S. Army standpoint, the JLSG is a sustainment brigade on steroids that not only supports its Army counterparts, but also supports the air and maritime components, supports deployment and redeployment, and serves as an intermediary between the national support elements (NSEs) and the tactical forces assigned to the JTF. It can be similar to a sustainment brigade and an Expeditionary Sustainment Command (ESC) rolled into one. Ultimately, the size and composition of the JLSG in any particular operation is determined by the overall size of the JTF it supports.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE JLSG?

The main purpose for creating and utilizing the JLSG is to enable greater cooperation in logistics across NATO, optimize the logistic footprint for any given NATO operation, and reduce the overall expense of logistics to NATO and the contributing nations. While not yet completely proven in major combat operations (peacekeeping operations and exercises aside), the JLSG seeks to gain these advantages by employing a JLSG made up of a core staff element with augmentation, as well as a host of subordinate units provided by various troop contributing nations, to collectively support a joint and multinational force. It is a given that no single nation can effectively and efficiently support its forces (and possibly others) in a NATO operation. Without a single headquarters to coordinate and streamline logistics in a particular area of operations, there is often significant redundancy and wasted effort when nations try to go at it alone.

The JLSG is meant to be the answer to those problems; it is an organization that supplements and eases the burden on national logistics, increases the overall unity of effort, and achieves greater economy of effort by optimizing the available forces and creating a single logistics command that can support the JTF commander. The JLSG, if utilized as planned, can also enhance the coordinated use of the existing logistics infrastructure, make the best use of national expertise to support the whole force, use common logistics funding more efficiently, and perhaps most importantly, provide the JTF commander a single, accurate, and timely logistical picture for the entire area of operations.

Many efficiencies can be gained by utilizing a JLSG as an operation progresses. While it may not be possible in the early stages of an operation, transitioning to a JLSG over time certainly improves the logistical situation. The effectiveness of the JLSG is further enhanced by utilizing several modes of multinational logistics, such as logistic lead nation, logistic role specialist nation, and multinational integrated logistic units, or multinational logistic units. The use of these modes is very similar to how the U.S. organizes for and executes joint logistics.

HOW IS THE JLSG STRUCTURED?

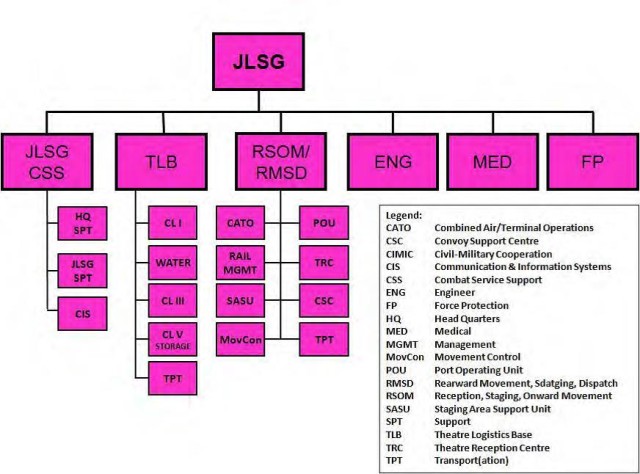

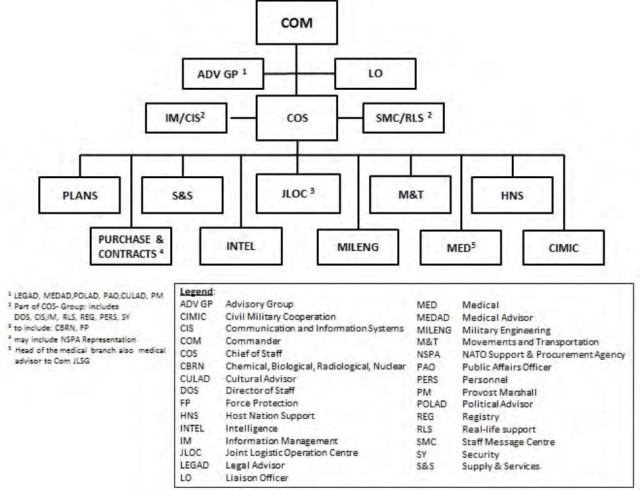

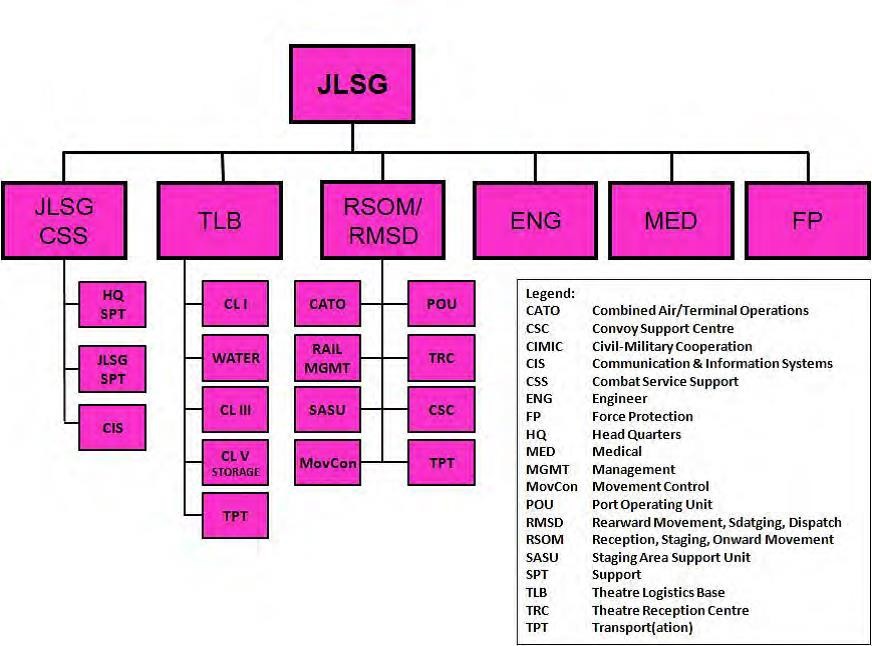

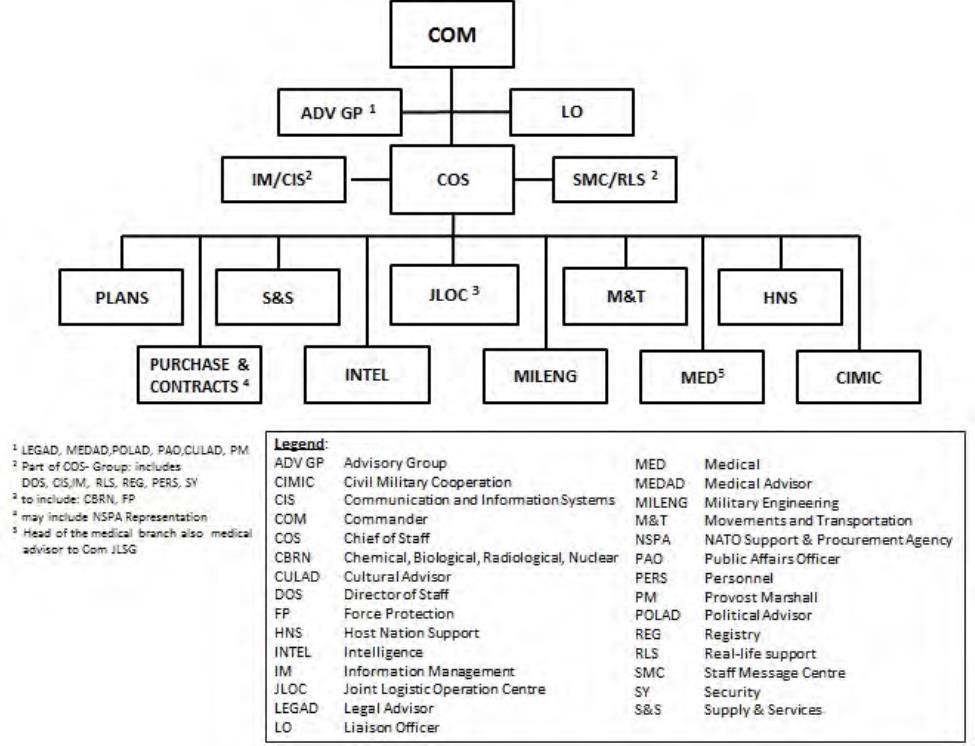

In order to support a variety of NATO missions and a multitude of nations, the structure of the JLSG must be incredibly flexible. It must be both tailorable and scalable to the specific operation. In smaller operations with few nations and limited joint requirements, the idea of the JLSG is easily executable. The challenge arises when the operation becomes more complex, the amount of nations involved increases, and the amount of support required by the air and maritime components increases. The proposed structure of the JLSG, however, lends itself to the robust responsibility it is tasked with in that type of scenario. In a perfect scenario, the JLSG not only has its headquarters section and its own internal support battalion, but also enough capability to operate a theater logistics base (TLB), operate one or more forward logistics bases (FLBs), execute distribution, and support the full spectrum of deployment and redeployment operations.

In addition to those "traditional" logistics functions and assets, the JLSG is designed to provide command and control to a host of engineer capabilities and advanced medical capabilities. In many cases, the JLSG also plays a significant role in coordinating, scheduling, and monitoring both host nation and contractor support. Host nation and contractor support can be incredible force multipliers when the JLSG doesn't have the assigned forces it might normally have.

WHERE ARE THE JLSGS?

Currently, there are four JLSGs. The two "tactical" JLSGs, which is the focus of this article, are at NATO Joint Force Command HQ in Brunssum, Belgium, and at NATO Joint Force Command HQ in Naples, Italy. They are each composed of a core staff element of about 25 personnel. That staff is augmented by approximately 95 additional personnel when "activated." Those additional personnel come from various other NATO or national HQs, including the NATO Force Integration Units (NFIUs), or from troop contributing nations depending on agreements made during force generation.

These two JLSGs are further supported by the newest NATO headquarters, the Joint Support and Enabling Command (JSEC), and its JLSG, which became initially operational capable (IOC) in Ulm, Germany, in September 2019. The JSEC, which is essentially the rear area command during operations, for will have the wartime mission of accelerating, coordinating, and safeguarding the movement of allied follow-on forces across European borders. The JLSG within the JSEC will, in turn, be primarily responsible for NATO�s reception, staging and onward movement (RSOM) mission. This could ease the burden on a "tactical" JLSG in some situations.

The fourth JLSG, also known as the Standing JLSG (SJLSG), is also starting to build capacity and is located at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Mons, Belgium. It will eventually move to Ulm, Germany, to be co-located with the JSEC. The SJLSG will be a predominantly non-deployable static and strategic level headquarters. To a U.S. Army officer, this is more akin to a Theater Sustainment Command (TSC). At present, the SJLSG's mission as described in AJP-4, Allied Joint Doctrine for Logistics, is to enable the responsive deployment and employment of NATO forces by conducting enduring, continuous, and proactive planning and enabling activities.

In addition, the SJLSG is responsible for the execution of joint logistics in support of NATO High Readiness Forces, including the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF). That mission was defined before the creation of the JSEC and its JLSG under the NATO Command Structure Adaptation, and it has yet to be written in NATO doctrine how the SJLSG mission (and perhaps others) will change to accommodate the new structure. While it is a bit unclear about what the future holds for the SJLSG�s mission, it is clear that the actual structure and composition of a "tactical" JLSG HQ will differ from operation to operation, and its success is largely dependent on it having the manning, expertise and subordinate units to execute its mission.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF THE "TACTICAL" JLSG?

One of the questions asked early on in CJSE-19 by participating officers in the JLSG was, "What exactly is the JLSG supposed to do?" To a U.S. Army officer accustomed to large scale, high tempo, multi-service, or joint operations, the answer to that question may seem obvious, but a majority of the officers in this exercise were from Sweden and Finland, and the concept of the JLSG (or its equivalent) doesn't really exist in their force structure. The same holds true for many nations that have smaller and less robust militaries.

Much of their logistics expertise and experience lies at the battalion level and below and is focused on their respective nation and component. The thought of executing logistics operations at brigade level and above is simply something they don't get a chance to do until they reach a certain level and have an opportunity to serve in a larger multinational logistics headquarters. So, there was a steep learning curve for many officers when it came to determining what exactly the JLSG was supposed to do and what role it played in the overall scheme of theater logistics.

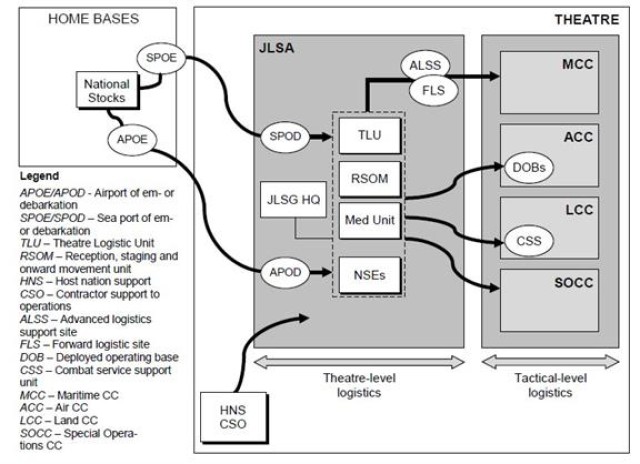

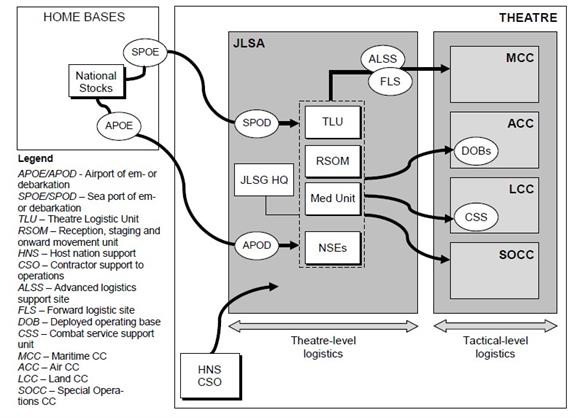

In most cases, a single "tactical" JLSG will deploy into an area of operations and set up its headquarters in a location deemed most advantageous by the commander. Sometimes that is near a significant aerial or sea port of debarkation; other times it is a geographically centered location that supports the overall distribution plan. What is likely is that the JLSG headquarters will be co-located with the main logistics base in the theater. That is commonly referred to as the TLB. The TLB serves as the main storage point and hub of distribution for most, if not all, equipment and supplies coming into a theater. From there, the JLSG has the best overview of the logistics situation and can provide the best command and control of its available assets. Some of the JLSG subordinate units will also be located at the TLB, but it is likely some of them will also be dispersed to other locations in order to facilitate the most effective and efficient flow of equipment and supplies, and to provide services, to the components.

In the most basic sense, logistics in NATO is a national responsibility. But, as mentioned before, very few nations, if any, can execute that mission all on their own. That is why the JLSG exists and why different modes of multinational logistics are employed. In a generic area of operations, as seen in Figure 4, the JLSG is responsible for monitoring and executing the logistics mission in the joint logistics support area (JLSA). This area is also called the joint logistics support network (JLSN) in the latest version of AJP-4 and AJP-4.6.

The JLSA (or JLSN) encompasses everything from the ports of debarkation down to the logistics elements belonging to the component commands. Nations send their equipment and supplies from home bases to the entry points within the theater and ultimately to a TLB. In most cases, the NSEs maintain some level of control of that material until it is needed. Then the JLSG assumes the responsibility for distributing when necessary. Other times, the NSEs turn over equipment and supplies to the JLSG once they enter theater. This is especially applicable when a nation is providing a common supply to all participating nations.

Once equipment and supplies from the nations reach the TLB, along with the materials and supplies provided by the host nation, it is up to the JLSG to manage their storage and distribution. In order to create a more effective distribution network, and at times shorten the lines of communication, the JLSG can set up forward logistics elements (FLEs). These sites are closer to the customer locations and give the JLSG more flexibility when executing its mission. These FLEs can be in addition to or co-located with the logistics elements of the components, such as a forward logistics site (FLS) for the maritime component or a deployed operating base (DOB) for the air component.

Either way, once the JLSG gets the right equipment and supplies to the components, whether it be at an FLS, DOB, or other location, the components are responsible for executing the remainder of the distribution mission. Of course, there are times when the JLSG can utilize its assets to throughput down to a lower level, but it isn't all that common. In addition, there are also times when the NSEs can bypass the JLSG and the TLB and deliver directly to the necessary component. This is especially common when a nation only has a small contingent within a particular component providing a specialized service that requires less common equipment and supplies. In this situation, whether the JLSG is directly involved or not, it is critical for all parties involved to coordinate and synchronize as much as possible to avoid confusion or a redundancy of effort.

WHAT CHALLENGES DID THIS JLSG FACE?

Throughout CJSE-19 there were several challenges that the staff of the JLSG faced. Some of these challenges were associated with a lack of overall experience, some could be attributed to the construct of the exercise, but there were some that could be common to any JLSG in any given scenario. It was also evident that there could be some "natural" challenges to the JLSG simply because of the way it is designed to be manned and utilized.

The first major challenge the JLSG faces is manning. This is a challenge associated with how the JLSG was designed. The 25-man core staff element is only a fraction of what is required to actually man and run the JLSG in a real-world situation. The bulk of the staff is actually made up of 95 augmented personnel. In a perfect world, all 95 billets would be filled by fully qualified personnel and this wouldn't be an issue. But it might be a stretch to think that can really happen, especially since there isn't necessarily a plan for where all 95 personnel will come from. It is likely some will come from other national or NATO HQs, or that other troop contributing nations will pony up personnel, but nothing is guaranteed. In a large scale crisis, some nations and NATO HQs may not have the wiggle room to give up personnel to man the JLSG. It's a roll of the dice, and without a full staff, the JLSG could struggle to accomplish its massive mission.

The second major challenge is again related to how the JLSG is doctrinally designed to operate, and it involves the command, control, and coordinating relationships. Some of this challenge is related to the relationships recommended by doctrine, while some of it is related to having a good understanding of what those relationships actually mean. It is important to note that NATO doctrine uses the term "degrees of authority" when discussing the level of command or control that a headquarters has over its subordinate units.

Some of those levels differ from what the U.S. and other nations use, so therein lies part of the challenge itself. In any case, nations never give full command and control of their forces to a NATO commander. Instead, nations will delegate only operational command (OPCOM) or operational control (OPCON). In the case of the JLSG, it is designed to be under the OPCON of a JTF HQ. The same goes for the units subordinate to the JLSG.

Technically, that means the JTF or JLSG commander can direct subordinate units to accomplish specific missions or tasks, which are usually limited by an agreed upon function, time, or location. Those commanders can also retain or assign tactical control to those units. In theory, this OPCON relationship gives both the JTF and JLSG commander some flexibility in terms of how assigned units are organized, positioned, and tasked.

However, in reality, it isn't as simple as that. Just because the doctrine says that is the relationship that should exist, that doesn't mean it is always the case. Nations often send forces with caveats that can tie the hands of commanders. Some caveats won't allow units to accept certain tasks, go certain places, or allow their forces to be re-task organized even if it is all for the good of the overall mission. From a logistics perspective, this can really hamstring a commander. It is important to iron out all of those details before an operation begins in order to prevent frustration and confusion in the midst of a conflict.

Another important point to make here is the difference between the NATO definition of OPCON and the U.S. definition of OPCON. In NATO, OPCON means that a commander has the authority to direct forces assigned so that they can accomplish specific missions or tasks, which are usually limited by function, time, or location and to deploy units concerned, and to retain or assign tactical control to those units. This does not include, however, the authority to assign separate employment of components of the units concerned.

In contrast, U.S. joint doctrine defines OPCON as the authority to perform the functions of command over subordinate forces that involve organizing and employing commands and forces, assigning tasks, designating objectives, and giving authoritative direction necessary to accomplish the mission. The key difference is the fact the U.S. version of OPCON provides the authority to task organize, while the NATO version does not. This highlights the importance of shared understanding across all commands and nations when it comes to command, control, and coordinating relationships.

NATO also has another degree of authority that differs from U.S. doctrine. Logistic control, or LOGCON, is the authority given to a commander over assigned logistics units and organizations within the joint operations area (JOA), including NSEs, that allows him or her to synchronize, prioritize, and integrate logistics functions and activities in order to accomplish the overall mission. The authority given in LOGCON does not extend to nationally owned resources, unless that is agreed upon in advance. The closest U.S. command relationship to LOGCON is support, in which the supported commander is given access to supporting capabilities and has the authority to provide general direction, designate and prioritize missions or objectives, and other actions for coordination and efficiency. Again, this point highlights the need for a clear understanding up front of what command, control, and coordinating relationships are in place and what they mean to all parties involved.

The next set of challenges has more to do with the execution side of things. While the challenges observed during CJSE-19 were true only of that particular exercise, all of them could be possible in any environment in which the JLSG operates. The first such challenge is the reporting and requisition processes. This isn't a unique challenge by any means, but it is one that can emerge and become a much bigger issue if it isn't addressed before an operation or very early on in an operation. There must be clear procedures and guidelines, as well as formats and timelines, for both reporting and requisitioning. This may seem like common sense, but in a NATO environment where units come together never having worked together before, this could get overlooked. Plus, differences in language and standard operating procedures exacerbate the situation. Therefore, it is important to either put these processes in orders during planning or codify them with all key players during the initial stages of an operation.

The second execution challenge revolves around the recognized logistics picture (RLP). The RLP is essentially what U.S. logisticians call the logistics common operational picture (LCOP). According to AJP-4, the JTF J4 is responsible for development and maintenance of the RLP. The same publication states that the JLSG, along with the troop contributing nations, component commands, and host nation, contributes to the RLP. In AJP-4.6, the JLSG is given the responsibility to contribute to the RLP in accordance with the direction and guidance of the JTF commander. So, from a doctrinal perspective, it is the JTF J4's responsibility to develop and maintain the RLP with support from others. In CJSE-19, however, the JTF J4 assumed the JLSG would manage the RLP.

The J4 provided some guidance, but not much. This was met with some dissension and created confusion. For the first few days there was no sign of an RLP. The JLSG wanted to adhere to doctrine, but the J4 knew the majority of the relevant information existed in the JLSG. From this observer�s perspective, the J4 was absolutely right. The JLSG has much more visibility and access to the information necessary for a complete RLP. They have direct coordination with the components, host nation, national support elements, and contractors on a regular basis. They routinely receive reports from these entities. The J4 may have some of the same communication and receive some of the same information, but they don't have nearly as many touch points or the level of fidelity of the JLSG. The J4 eventually codified their delegation of this responsibility in a fragmentary order (FRAGORD), but this occurred only after valuable exercise time was lost. In the future, the J4 should make their wishes concerning the RLP known as soon as possible, and ensure all key players understand their role in the RLP sooner than later.

The third execution challenge may have been a product of this particular exercise construct, but it is worth mentioning nonetheless. As mentioned before, the nations are ultimately responsible for providing much of the equipment and supplies for their participating units. In order for the JLSG to have the visibility it needs to plan and coordinate distribution (and produce the RLP), the NSEs must provide accurate and timely information. In the case of CJSE-19, the nations were unable to provide that information in a timely manner, therefore, the JLSG was often in the dark as to what the nations were bringing in to the TLB or directly to the components. The JLSG (or the JTF for that matter) don't really have the authority to "task" the NSEs to provide this information, so it is imperative that they use their coordinating authority to ensure the NSEs communicate accurate and timely information. This will help the JLSG plan and coordinate distribution and allow them to paint an even clearer picture for the JTF commander in the RLP.

An extension of this challenge that in and of itself could be a separate discussion, is the fact that interoperability of information systems is largely non-existent in a multinational environment. This makes the problem of providing a clear RLP even more difficult, especially when it creates a redundancy of effort for subordinate units who have to transfer data and information into whatever format the higher command wants, which is very likely not the same format their system provides.

WHAT ADVANTAGES DOES THE JLSG HAVE?

It wasn't all gloom and doom for the JLSG during CJSE-19, and the advantages such an organization brings to the fight were highlighted on many occasions. It is important to acknowledge those positive aspects as well, because it is very likely that the concept of the JLSG is here to stay. The success of the JLSG in NATO�s Trident Juncture 18 is another beacon of light in the relatively short history of the JLSG. In that particular exercise, the JLSG was made up of 24 different nations and over a two month period it deployed, sustained, and redeployed over 50,000 troops and 10,000 vehicles from 31 different nations. Many in NATO see that as a modern proof of concept that can be built upon in exercises and operations for years to come. The JLSG concept, with the addition of the SJLSG and the JSEC, will be tested again in the upcoming Steadfast Defender exercise.

So, what advantages does the JLSG have if the headquarters is manned properly and given an appropriate assortment of subordinate units?

The most obvious advantage is the fact that the JLSG could be a single headquarters that can coordinate and synchronize all logistics functions throughout an entire JOA. In the perfect situation the JLSG is the one-stop shop for anything logistics, has complete visibility of equipment and supplies as they flow from nations down to customer units, and has the ability to prioritize efforts in accordance with the commander�s guidance. Granted, there are a lot of obstacles to making this a reality, but in the right environment that is truly what the JLSG can be. The second advantage is the economy of effort that JLSG can provide by utilizing common services. It is clear that not every logistics function or requirement is interchangeable, but there are many that are, and that is where the JLSG can really pay off. Some things that come to mind as universal or interchangeable are water production, vehicle recovery, and contracting.

To some extent, advanced medical care can be added to the list. Perhaps the biggest advantage the JLSG brings is with supply storage and distribution. Yes, nations might have different kinds of supplies or parts, but the JLSG can gain significant efficiency through common storage and distribution. This may be a little more challenging outside of the JOA, but once inside the JOA the use of common storage facilities and distribution networks not only save time and money, but they also reduce the amount of troops on the ground necessary to complete the mission. In CJSE-19, this is one area where the JLSG excelled. Once the JLSG gained good visibility of each nation�s supplies and understood what needed to go where, they were stellar about utilizing common transportation assets (on land, in the air, and at sea) to conduct efficient distribution. Instead of having ten nations trying to deliver supplies over the same period of time along the same main supply route (MSR), the JLSG had its subordinate transportation battalions moving supplies from the common storage location to all nations involved. The JLSG had the visibility it needed, and they were able to prioritize with the success of the overall mission in mind as opposed to just the interests of a particular nation. These advantages, when allowed to shine, are what really make the JLSG a concept that can improve an operation.

WHERE MIGHT THE U.S. ARMY FIT INTO THE JLSG?

The JLSG is a uniquely NATO concept. It is built around the idea that a single unit, made up of different nations and services, will provide logistics command and control to a joint, multinational force. The JLSG, in most cases, will also have the support of both contractors and a host nation. In the U.S. Army, we are accustomed to providing support to other services and other nations, but the situation the JLSG likely faces is far more complex than any ESC or sustainment brigade has faced or will face. That being said, a question left to ponder is where does the U.S. Army fit into the concept of the JLSG? It seems likely that U.S. Army officers, NCOs, and Soldiers could fill some of the positions on a JLSG staff.

The right amount of joint and multinational experience exists throughout the ranks. It is also quite possible that U.S. Army logistics, medical, or engineer battalions, companies, or detachments could be plugged into the JLSG in some way. There are considerations to be given to the level of authority granted to higher commands in this case, but the capabilities the U.S. can bring to bear are certainly valuable in any situation. Lastly, but not very likely, it is entirely possible that an augmented ESC or sustainment brigade could operate as the JLSG itself.

In both cases, there would be a need for both joint and multinational augmentation, especially from nations participating in the particular operation, and a fair amount of consideration given to the level of authority of the U.S. commander. The positive aspect of such a move is that the majority of the staff would be familiar with one another, and if the preponderance of the supported force was from the U.S., they would also be familiar with the customer base. In any case, there are several ways the U.S. Army could be worked into the concept of the JLSG. At this point, it is just important to understand what the JLSG was designed to do and the purpose behind utilizing such an organization in a NATO operation with a joint and multinational flair.

--------------------

Lt. Col. Aaron Cornett is an instructor and lecturer at the Baltic Defense College, Tartu, Estonia. He has served as an instructor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; as a sustainment observer, coach/trainer at the Mission Command Training Program; and as Service Support Company commander, and group logistics officer, S-4, at 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne). He holds a bachelor's and master's degree in journalism from University of Kansas.

Retired Col. Zeljko Idek, a lecturer at the Baltic Defense College, and Dr. Tom Ward, a professor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, provided significant and noteworthy contributions to this article.

--------------------

This article was published in the January-March 2020 issue of Army Sustainment.

Social Sharing