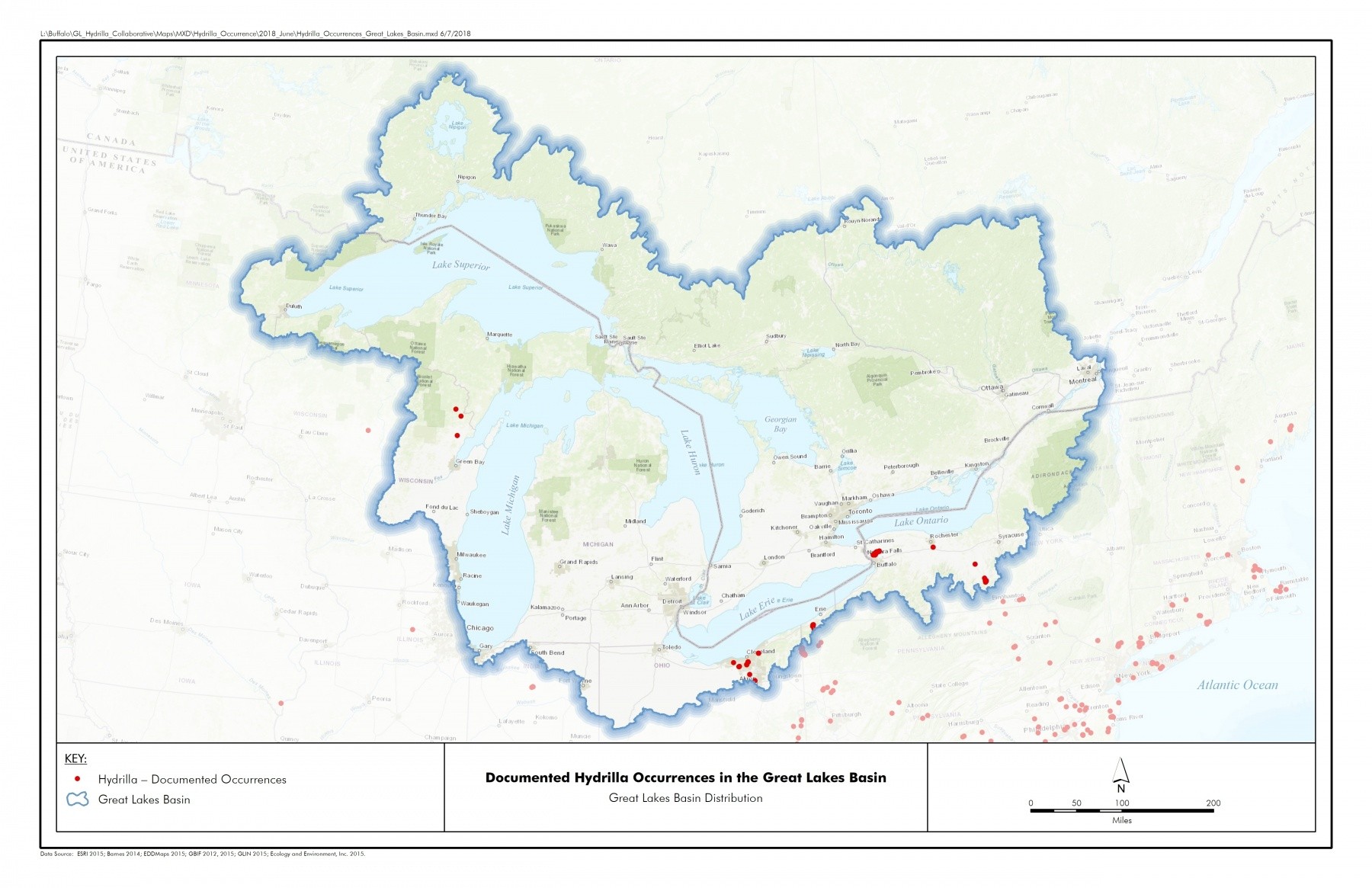

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Buffalo District is on a mission to fight hydrilla, an aggressive plant species that has wreaked havoc from Asia to every continent except Antarctica.

"Hydrilla completely chokes out our waterways and impacts all the things we enjoy," said Michael Greer, USACE Buffalo District project manager. "It affects water quality, the economy, businesses, hydropower and flood reduction - ultimately our health and our wallets."

"A single aquatic plant could put all of that at risk," warned New York Senator Charles Schumer in 2017.

WHAT IS HYDRILLA? (Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Hydrilla is an aquatic plant that has earned the illustrious title "world's worst invasive aquatic plant". Listed as a federal noxious weed, hydrilla has made its home in just about every conceivable freshwater habitat including: rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, marshes, canals, ditches and reservoirs.

Hydrilla was first discovered in the United States in the 1960s in Florida. Since then, it has spread to many parts of the U.S.

Hydrilla can grow in a wide variety of water conditions (e.g., high/low nutrients, high/low turbidity, variable pH, up to 7% salinity) and water temperatures. Unlike most native aquatic plants, hydrilla is capable of growing under extremely low light conditions. Hydrilla is able to begin photosynthesizing much earlier in the morning than native plants so it is able to capture most of the carbon dioxide in the water (which limits growth of other plants). Hydrilla grows very rapidly (it can double its biomass every two weeks in summer) and has no natural predators or diseases to limit its population.

Dense infestations of hydrilla can shade or crowd out all other native aquatic plants, alter water chemistry, cause dramatic swings in dissolved oxygen levels, increase water temperatures, and affect the diversity and abundance of fish populations.

BUFFALO DISTRICT PROJECTS AND TREATMENTS

Buffalo District's main projects to eradicate hydrilla are at the Erie Canal and Tonawanda Creek, Tonawanda, NY, as well as on Cayuga Lake near Aurora, NY and Ithaca, NY. The District provides assistance on Pymatuning Lake which borders Pennsylvania and Ohio, and at Raystown Lake in south central Pennsylvania. Buffalo District is also lending expertise to a project on the Connecticut River.

"Treatment for each project is very unique. We use different EPA-approved herbicides at each project based on site specific evaluations," said Greer. "We know how important water and the Great Lakes are to us all, so we make sure it's safe for the environment."

"Herbicides are the safest, most effective way of eliminating hydrilla without actually spreading it around," said Rich Ruby, USACE Buffalo District biologist. "At the Erie Canal we use contact herbicide, meaning we apply it once, it acts quickly, and then it's done."

Treatment decision-making is driven by the herbicide's properties and the site's water conditions, such as water exchange and potable water use. Still, there is a trial-and-error component, in large part because of unpredictable water conditions.

"In a canal there's a flowing system. In a lake, there may be large areas of open water subject to high rates of exchange or there could be protected bays, and every day on every lake has different dynamics," said Greer. "Despite that, we've been very successful in Aurora for the last three years and have drastically reduced hydrilla. In Ithaca we didn't find any hydrilla this year. We still have to monitor and do treatments because we know we probably removed about 90 percent of what was there."

Ninety-percent is a good start, but it takes a long-term commitment to achieve eradication according to Greer. Why?

TUBERS

Tubers are hydrilla's reproductive structure, and the plant can make dozens and dozens of new tubers in warm water temperatures. If only 10 percent of those tubers remain in the sediment it can leave the next generation with exponentially more hydrilla.

"Luckily, there's a very susceptible point in hydrilla's life cycle," said Greer.

The Buffalo District team treats hydrilla in late July to early August when the plant hasn't started producing new tubers. Also, tubers already in the sediment sprout at the same time (known as synchronous sprouting) so the team applies a single, well-timed dose of herbicide to kill 90 percent of the plants at once.

"Mathematically, reducing hydrilla by 90 percent every year never gets to zero, but you can get pretty close. We're making ground but it takes time," Greer explained. "Typically experts recommend treating for about three years after no hydrilla detections and then monitoring another year or two just to see if there is any regrowth."

THE WAY FORWARD

Buffalo District and Greer have tackled the hydrilla problem since 2013, but the invasive plant is new enough that there aren't many records of success or failure. Every year, the Buffalo District team collaborates with researchers from the University of Florida's Center for Aquatic Invasive Species and the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center to look at data and discuss the way ahead as a team.

"We're on the leading edge of this fight and nobody has a monopoly on good ideas," said Greer. "Each year we think of new ideas and treatment strategies, as well as how to explain these ideas to stakeholders and see if there's buy-in from them."

Project partners include New York State Canal Corporation, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Environmental Protection Agency, the University of Florida, and various local partners.

"We've learned a lot as an organization and our team members have expanded their technical expertise," said Greer. "It's been really rewarding in that respect. It's been a District-wide effort."

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The Corps of Engineers is authorized to treat Hydrilla (hydrilla verticillata) under Section 104 of the River and Harbor Act of 1958, through the Aquatic Plant Control Research Program. Funding for the project is available through the Corps of Engineers Aquatic Plant Control Research Program and Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

Social Sharing