FORT LEONARD WOOD, Mo. - From facing off the Soviets in the Cold War to repeat deployments on Overseas Contingency Operations, Command Sgt. Maj. Ted Lopez, U.S. Army Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear School, has spent the majority of his 30-year career in line units training and leading Soldiers.

"Starting with my great-grandfather, all the men in my family have served in the military," Lopez said.

His Uncle Louis was captured by the Japanese in World War II. He survived the Bataan Death March, and was working in Japanese coal mines when America bombed Nagasaki.

"He said that he felt the blast and saw a big cloud, and they (he and the other prisoners) knew the war was over," Lopez said.

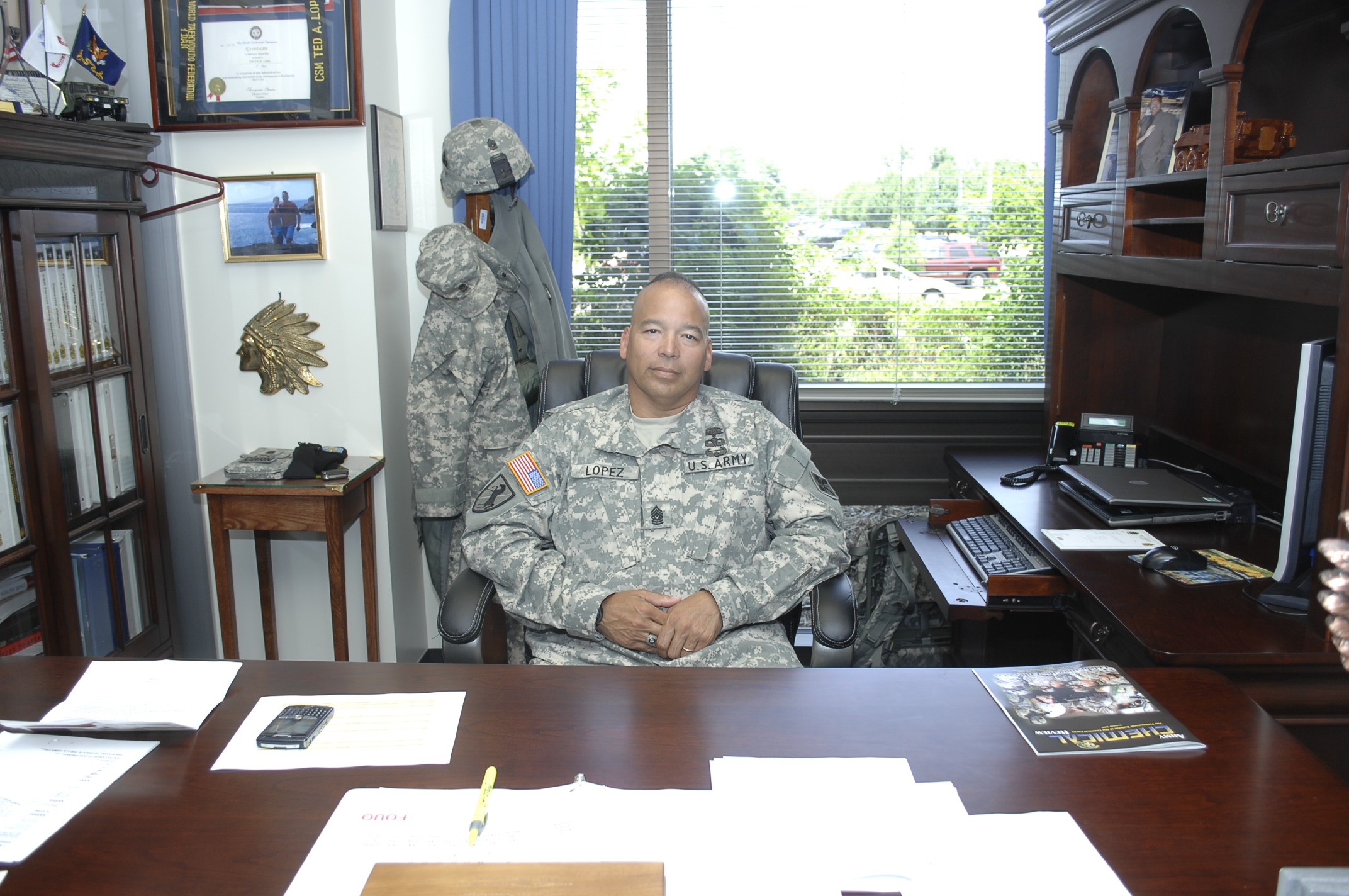

Family military heritage plays a large part of Lopez' life. Sitting in an office, surrounded with so many plaques and mementos that a visitor might mistake them for wallpaper, Lopez talks about wearing his father's Marine cufflinks at every formal function, and brushes off a black belt in Taekwondo as "just a part of physical training" while stationed in Korea.

Lopez' initial Army story mirrors that of many recruits today. He tried college after high school, but realized he was not ready for it and joined the Army as a medic. He was on terminal leave at the end of his first enlistment, when a retention noncommissioned officer told him he could reenlist in the Chemical Corps for a bonus.

"It caught my eye," Lopez said. "The next thing I was at Fort McClellan, Ala., getting trained, and I loved it. Come August, it'll be 30 years, and I have never regretted a day."

Lopez talked about his time in Germany during the Cold War serving under the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. One morning his unit got an early alert. Lopez' reconnaissance platoon rolled out to man their defensive positions against a possible Russian attack.

"We got there and people were literally running at us," Lopez said. "Our (combat) job was to screen and hold and hopefully the cavalry would arrive. We had a pretty short life expectancy. But there was no build up, no formation, no tanks. These civilians were hugging us. It was chaos. We finally got word what was going on - the wall fell."

Lopez talked about the effect of the end of the Cold War on the Army.

"As an Army, we felt out of place," Lopez said. "The wall is down - now what' Then Desert Storm came along.

"I remember sitting in Iraq during Desert Storm saying, 'Man, I do not want to be here ever again,'" Lopez said. "I've been to (Iraq and Afghanistan) eight to ten times now, if you include command visits. I will never say never again.

"When we deployed to Desert Shield/Desert Storm, the equipment didn't even come close to what we have now," Lopez said. "Our Soldiers today get the greatest training and equipment I've seen in all my 30 years (service). I wish you could see what it was like during the Persian Gulf War - (compared to today's Army) it's night and day."

Lopez was at Fort Polk, La., in a staff meeting when 9/11 happened. Later that week, he was called back to headquarters from a weekend safety formation.

"Staff duty said, 'You have to report now to the Pentagon with all your assets,'" Lopez said. "I had never heard 'now' before. We worked Friday all night long preparing to deploy.

"I'll never forget Saturday standing at the airport in Alexandria watching plane after plane come in to load up our equipment," Lopez continued. "By noon Sunday, we were operational doing biological agent detection systems surveillance around the Pentagon."

Lopez felt that his time spent in other Army branches, especially as the command sergeants major for the 1st Maneuver Enhancement Brigade and the Division Support Command, has given him a different perspective on the Army.

"You can't just stay centric to your military occupational specialty," Lopez said. "A lot of our (CBRN) NCOs serve out in those brigade combat teams. They have to understand what's going on in their units.

"First and foremost, you're a warrior," Lopez said. "But you add (CBRN) expertise. You're got to earn the right to be in that unit, then they'll listen to you. You need to get the leadership to buy into the fact that they need extra (CBRN) training."

Lopez illustrated his point through a life story from when he belonged to a field artillery unit that was headed to a National Training Center rotation.

"I put two (artillery) batteries through a hard time in the CBRN world," Lopez said. "They were literally crying because I wouldn't let them out of MOPP 4 until they did their task properly."

Lopez got the units to where they could do an emergency call for fire mission in full MOPP in eight minutes - two minutes faster than the time standard. The training paid off at their NTC rotation.

"We won," Lopez said. "A nearby infantry unit was zero strength, but our field artillery unit was 100 per cent strength and still firing rounds out of the tubes at ENDEX (the end of the exercise)."

Lopez talked about the difficult parts of his Army career, remembering when a battalion lost four Soldiers in an attack.

"My hardest time is when we lose Soldiers," Lopez said. "It will never get any easier. Looking a family in the eye (when they have lost a loved one) is a tough time. You can't falter - I don't think you ever get good at it.

"Last week at Fort Bragg, N.C., a Soldier asked me how someone with 30 years of service stays motivated," Lopez said. "I told him, 'It's you guys.' Every time I see one of our young Soldiers being successful, watching our young Soldiers perform, it gives you another year to go on."

(Carolyn Erickson is a photojournalist with the Fort Leonard Wood GUIDON.)

-30-

Social Sharing