JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-FORT SAM HOUSTON, Texas -- Todd Unruh never believed they were going to die. Even covered in glass, in pain and flying blind, the pilot felt a sense of calm.

"At no point did I think about my daughter being without a father; I didn't let that emotion come into play," he said.

It was a confidence he had yet to impart to Jason Schroeder, his sole passenger, who was blissfully unaware he was about to fly a plane for the first time.

It was clear skies on Oct. 31 when Unruh, an experienced corporate pilot, took off from Dallas to fly Schroeder to New Braunfels, Texas, for a business meeting in a twin turboprop, 12-seater plane. On approach to the airport, Unruh lowered the nose and pulled the power back to idle in preparation for landing. He had just silenced the gear warning when he looked up and saw what he believes was a hawk in a deep dive.

"We were traveling about 250 miles per hour when I saw him flying knife-edge heading straight down into our flight path," Unruh said.

Before he could react, the bird slammed into the windshield on Unruh's side. The glass shattered into tiny pieces and sprayed across the cockpit. Unruh tried to close his eyes in time and duck, but the glass impaled his eyes.

"When I closed my eyes, I heard the crunching of glass," he said. Ignoring the pain, Unruh wiped the blood from his face and picked up the microphone to alert the air tower of an emergency.

"I was trying to open my eyes to see but it was excruciating," Unruh said. He felt dizzy but knew if he passed out, he and Schroeder wouldn't make it. With the plane heading downward, he took a few deep breaths and called out. "Jason, I need you up here now!"

Schroeder, who had heard the boom of the bird hitting and the window exploding, already was on his way.

"I sat in the copilot seat and asked him what I could do," he said. "I could see Todd was in pain and struggling with not being able to see. It was extremely tense."

Temporarily blinded, Unruh instructed Schroeder to help keep the plane level as the pilot kept his hand on the control wheel and nudged the plane back into an upward ascent. He guided Schroeder by memory to the gauges he needed to monitor.

Once they had reached a safe flight speed and altitude, Unruh took a deep breath. "I told Jason that we had plenty of fuel and we could fly around all day and to worry about landing later, just work on flying the plane."

Still, Unruh felt the plane swaying from side to side. "I asked Jason why he was going back and forth. He told me that he was weaving between houses so if we crashed, we wouldn't kill anyone," the pilot said with tears in his eyes.

In the meantime, the traffic controllers cleared the runways and alerted approaching planes to steer clear as the men circled overhead.

With Schroeder calling out the landmarks and keeping an eye on the gauges, Unruh, who was familiar with the airport, locked in a mental image of their location and how they needed to approach the runway. They lined up for landing, and the pilot lowered the gear and flaps as the navigation system called out their approach -- 50 feet, 20 feet, 10 … Unruh pulled back the power levers to idol and the plane finally touched down. He hit the brakes and the plane abruptly came to a stop just inches away from the end of the runway.

"I turned off the power and electric and just sat there for a moment," Unruh said. "So many things could have gone wrong. Jason was incredible. If he wasn't there, I wouldn't be here."

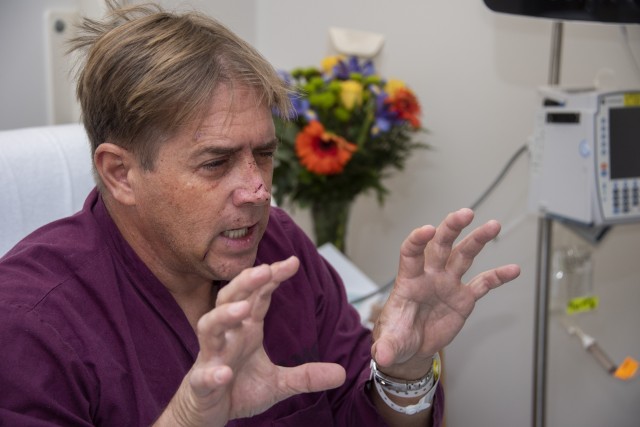

An ambulance rushed Unruh to Brooke Army Medical Center's Level I Trauma Center for care. The next morning, a specialized team removed the pieces of glass from Unruh's eyes, along with the damaged natural lens from his left eye.

"Todd's injury was similar to the types of blast injuries we see downrange; the same type of bilateral blast tattooing," said Col. Darrel Carlton, BAMC ophthalmologist. "But in Todd's case it was glass rather than rock or granite."

Unruh said he's grateful for the high level of care and positive prognosis for recovery he's received. "For a pilot, vision is everything," he said.

Now recovering back home in Daytona, Fla., Unruh plans to return to BAMC for follow-up care. Looking forward, the pilot is eager for his eyes to heal so he can get back in the cockpit.

As for Schroeder, he plans to learn to fly, specifically land, in case he ever needs to draw on those skills again.

In fact, he's already lined up an instructor. "I'll wait as long as I need to for Todd," Schroeder said. "There's no better instructor out there."

Social Sharing