Chief Warrant Officer 5 John Carnell spent many of the first 20 years of his 36-year career assigned to remote locations throughout the world.

Now, in retirement, he will soon find himself in yet another remote location - the dinosaur-rich lands of Wyoming and Utah.

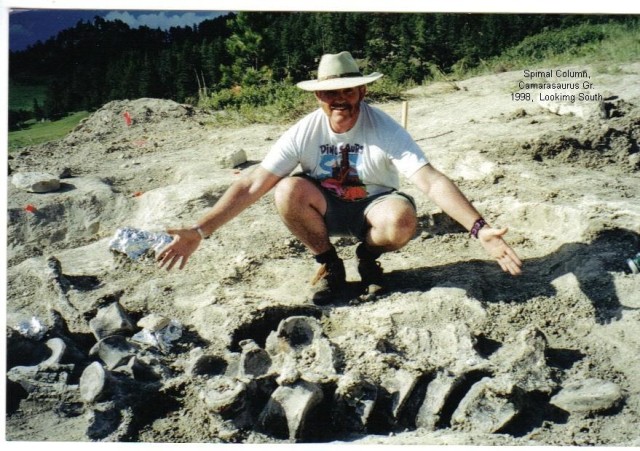

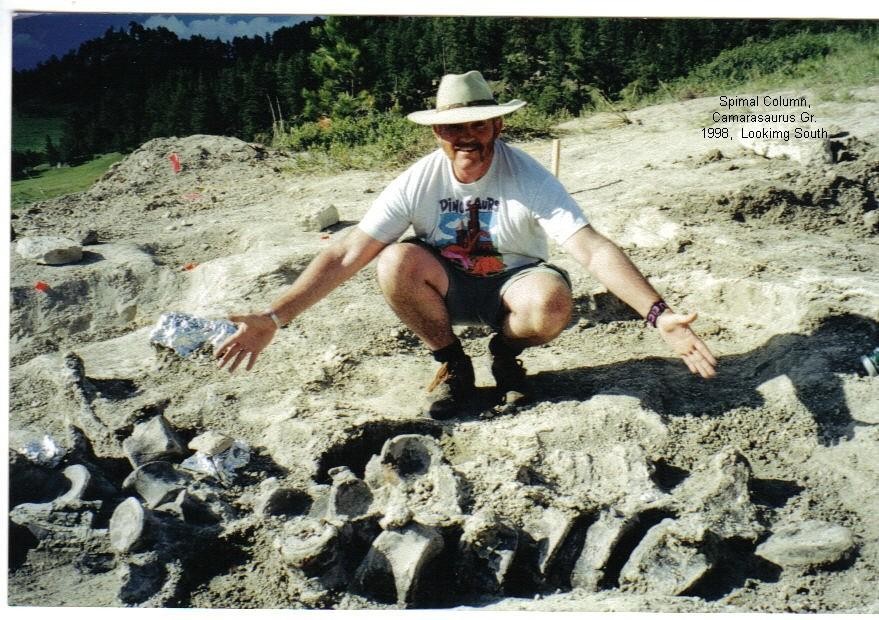

Since 1992, this paleontologist volunteer has spent many summer vacations aiding in the recovery of dinosaur bones in the U.S., Europe and the People's Republic of China. Carnell fell in love with his hobby while stationed in Germany, where he visited Humboldt University and discovered their exhibit of a Brachiosaurus that stands six stories high.

"I decided I wanted to be part of that," the 54-year-old retiree said, describing the Brachiosaurus. "So, I take time off in the summer to pull dinosaurs out of the ground."

Even though dinosaur digging seems a far cry from his work with the Army in the nuclear weapon and missile arenas, Carnell said both require technical knowledge.

"Both are meticulous. Both require a lot of attention to detail and procedures that are specific," he said.

It is the discovery of dinosaur bones that appeals to Carnell's scientific nature.

"When you first expose that dinosaur bone you are the first person to see the remains of that animal," he said. "No one has ever, ever seen those remains until you find them in the ground. Seventy percent of the animal is its back, legs and ribs. It's an awesome sight to behold. And when you are out there in the field digging you know you are making a major contribution to the scientific knowledge of dinosaurs."

A retirement ceremony for Carnell was held May 22. In his retirement speech, Carnell spoke about the Army's evolution from its negative post-Vietnam reputation to today's image as a technically advanced and Soldier-focused Army. During the early years of his career, Carnell watched the Army undergo a metamorphosis.

"The Army I joined had come out of Vietnam," he recalled. "It was an unpopular Army. It was demoralized. It didn't know what it was about. It was suffering from huge racial problems and drug problems. It was a difficult Army to be in because it did not know what this country wanted it to be."

In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, the Army's leadership rebuilt its own organization.

"Our leadership realized we had to get back to the basics of what Soldiering was all about," he said. "It was about taking care of Soldiers so they could do their jobs. The Army focused on its specific constitutional responsibility to fight and win wars. And the Army became a better Army."

"Reshaping the Army" meant establishing and enforcing standards, holding leaders responsible for their Soldier's tactical and technical proficiency, and achieving military excellence through leadership, hard work, tactical and technical competency, discipline and Soldier accountability.

The surprise came in 1991, when the Army was called on in Operation Desert Storm and quickly responded to put down the threat.

"We moved 70 percent of the Army halfway around the world," Carnell said. "It was the greatest movement of an Army ever. And when we accomplished the mission, we packed it all up and came home. We became a first class Army, the premier military force on earth."

Carnell's entire career has been filled with the quest to be the most technically proficient Soldier the Army has to offer. He began and ended his military career at Redstone Arsenal - being among the first Soldiers to be trained at Redstone as a nuclear weapons maintenance technician and then transferring to Redstone for the last time in 2005 as the logistics transformation officer for the Program Executive Office for Missiles and Space.

One of his last assignments with Missiles and Space involved a responsibility he came to enjoy the most in the Army -- mentoring and teaching young Soldiers.

"I managed a team of 60 people to train and issue the Army's newest artillery system - HIMARS - to the Wyoming National Guard," he said. "In 88 days, we trained that battalion, issued equipment and watched them successfully fire a missile with HIMARS. I really enjoyed the day-to-day contact with Soldiers."

Carnell joined the Army in 1973, after completing one year of college.

"I was tired of going to school. I was tired of being at home. I was frustrated as someone who didn't know what he wanted to do," he recalled.

One thing Carnell did know - he liked the idea of becoming a chief warrant officer like his father, who made the rank of CWO 4 during his 27-year Navy career. But, instead of the Navy, Carnell chose the Army for his career path.

"My recruiter wanted me to drive a tank. But I knew that wouldn't take me to warrant officer," he said. "So, I chose nuclear weapons maintenance technician for my military occupational specialty."

Carnell's MOS took him to Redstone Arsenal.

"I was in class number one for nuclear weapons at Redstone Arsenal," Carnell said. "That job specialty also gave me the opportunity to apply for chief warrant officer."

Carnell's job in nuclear weapons maintenance took him to assignments in New York, Colorado, Germany and Italy. In 1989, he was responsible for the safe evacuation and return of all Army nuclear weapons deployed to both Italy and Greece as required by NATO treaty agreements.

"We retrograded the nuclear weapons and returned them to the U.S. safely without leaving any environmental hazards of any kind," he said. "That was a super, super challenging mission because we had to accomplish the mission in a period of 120 days, and the last nuclear weapons in Germany and Turkey had to leave on the same day at the same time."

The NATO treaty eventually put Carnell out of a job. The Army ended its nuclear weapon business in 1992, and Carnell came back to Redstone Arsenal to retrain as a land combat missile maintainer. He was assigned to Fort Lewis, Wash., before assuming responsibility in 1996 for the Warrant Officer Candidate Academic Studies branch at For Rucker. Other assignments took him to Fort Bliss, Texas and then to Redstone Arsenal.

"I was a CWO 4 when I went to Fort Rucker. But that was the one assignment I was most apprehensive about," Carnell said. "It's a really important mission to train Soldiers who want to be warrant officers.

"It turned out to be tremendously rewarding to help train young high school graduates who wanted to fly helicopters and young Soldiers who were technically qualified sergeants or staff sergeants wanting to be warrant officers. While I was there, in excess of 4,000 Soldiers and high school kids became warrant officers in the Army. The generation of pilots who have done so wonderfully in this conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan were warrant officer candidates when I was at Fort Rucker. That was a hallmark of my career."

While chief warrant officers are called on to lead Soldiers, they must, first, be technically proficient in their career field.

"Warrant officers are the Army's specialists," Carnell said. "We are the knowledge base in the technical field areas for the Army. We provide the institutional knowledge in making complex systems work for the Army. Warrant officers work in complex, technically challenging fields."

Army training makes it possible for a Soldier to excel in any field they are interested in, he said. And nuclear weapons maintenance is no exception.

"The Army teaches you skills and you practice those skills," Carnell said. "You learn the basics and you practice. There's no real secret to being a warrant officer, a leader or taking care of Soldiers. It's all there for anyone to learn.

"But to be a warrant officer, you have to have a true desire to take on the job, to always do what's right, to live by the Army values, to do the best you can and to give your commander 100 percent."

Carnell said the Army will continue to be successful in its missions because of its philosophy toward caring for Soldiers and "being the Army the Constitution and the nation requires. We know how to fight and win the nation's wars."

The Army will continue to evolve into a better Army, he said, despite the wartime and budgetary challenges it faces. And Carnell sees that ongoing evolution in PEO for Missiles and Space.

"Our weapon systems, our Army doctrine, our management and logistics system and our professionalism continue to improve," he said.

"This PEO has been at the forefront of this Army transformation in the field of missiles. As its employees continue to spiral technical innovations into our systems, such as Patriot, MLRS, TOW, Javelin and helicopter-borne missiles, it is providing Soldiers the very best missile weapons systems possible, at an affordable price. The PEO's continued support to the war fighter, the American Soldier, is crucial and very much in evidence in this current fight. This PEO is leading the continuing Army transformation effort, achieving an excellence in missilery never seen before in any military force."

Besides digging up dinosaur bones, Carnell will spend his retirement with his wife, Kathleen, who is a logistics manager for the Integrated Material Management Center's Black Hawk Aircraft Depot Production and Acquisition Management Team, and his three stepchildren. He also will continue to be active with the local annual Brewfest and the Free the Hops/Alabamians for Specialty Beer organization.

Social Sharing