BOZEMAN, Mont. -- Yusufiyah wasn't the safest place to be. The Iraqi town southwest of Baghdad was in an area U.S. Soldiers called the "Triangle of Death" because so many had been killed there in the years following the 2003 invasion.

On a hot and muggy morning June 1, 2007, Staff Sgt. Travis Atkins, 31, and fellow Soldiers were searching for a missing or captured Soldier in the vicinity of Yusufiyah.

They'd been attacked earlier in the day. Now they noticed four suspicious-looking characters.

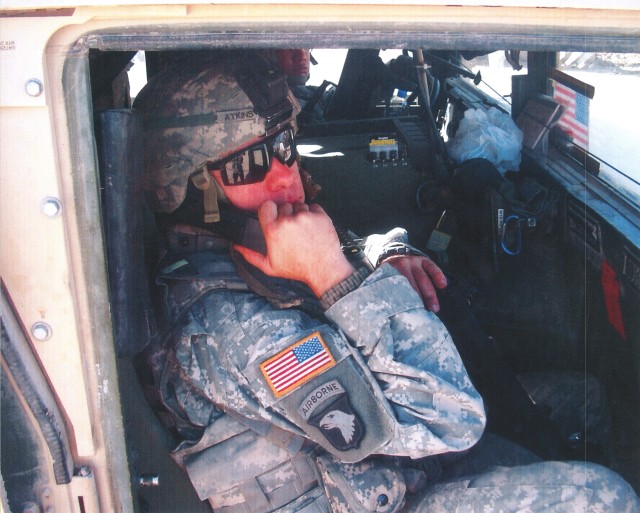

As the truck commander in his Humvee, Atkins ordered the driver to pull the vehicle up to the intersection so they could interdict the suspected insurgents. Once stopped, Atkins exited the vehicle and approached one of the men to check him for weapons while another Soldier covered him.

Travis understood the danger, said his father John "Jack" Atkins. But as a leader, Travis lived and breathed Army values.

Jack wasn't just saying that, he had been a paratrooper in Vietnam from 1965 to 1966, so he well understood the dangers his son faced and the Warrior Ethos that Army professionals live by.

Travis always wanted to be a Soldier, his father remembered, speaking from inside his Montana farm house, which has an expansive view of his 30-acre hay fields, birch forest and the towering mountain ranges in the distance. It was where Travis had lived since age 6.

Jack recalled when Travis was 12, back in 1987, he played Soldier with his younger sister Jennifer. He role-played a general and bestowed on her the rank of private. His army consisted of plastic toy soldiers.

But after high school in Bozeman, Travis did an assortment of blue-collar work, from painting and concrete work to jobs as a small-engine mechanic in the Montana towns of Belgrade, Bozeman and West Yellowstone. He also spent a year at Kemper Military School in Booneville, Missouri.

DECISION TO ENLIST

One day, at age 25, Travis realized he wasn't getting any younger and he'd have to make a decision about joining the Army, his father related, so he went to see the local recruiter in Bozeman.

After taking the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, which measures aptitude for the various military occupational specialties, a recruiter informed Travis that he scored high in mechanical aptitude and the Army thought he'd make a great helicopter mechanic, Jack said.

Travis was in fact very skilled with his hands, his father said. As a boy, he quickly learned to operate all of the farm vehicles.

Once, a younger Travis completely took apart a snowmobile, his father said. "I never thought he'd put it back together, much less that it would run." But it did.

Travis was, however, dead set on becoming an infantryman and told the recruiter in so many words that if he didn't get infantry, he wouldn't enlist. So he got his wish, his father said.

Following his enlistment Nov. 16, 2000, Travis completed infantry initial-entry training at Fort Benning, Georgia.

His parents, Jack and Elaine Atkins, attended the graduation ceremony. When it was over, Travis told his parents that going through basic combat training was the most fun he'd ever had, Elaine said.

"I don't think too many Soldiers would have told you that," Jack said. But he loved it. He loved the discipline and the physical and mental challenges and most of all, he loved to shoot.

Travis was a crack shot, his father said. Jack used to take his son on hunting trips all the time to places like West Yellowstone, where big game is plentiful.

They'd split up at daylight to hunt alone and then rendezvous at a designated spot around lunchtime. One day, Travis met his dad at the rendezvous point and told him that he'd bagged a deer.

So the two of them tramped through the fields and forests to where it was. "It was the biggest deer I'd ever seen," his father said. After dressing it, they carved it in half and the two of them each took half and carried it 1.5 miles back to the truck.

Travis carried a large, heavy-barreled rifle. Jack said he told him he'd never haul such a heavy gun across the terrain, but Travis insisted on it because of the challenge of bringing down game from a long distance that only could be done with a large-caliber gun.

AIR ASSAULT

Following infantry training at Benning, Travis was assigned to Alpha Company, 3rd Battalion, 327th Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Jack said he didn't know if his own Army service from 1963 to 1967 as a paratrooper and as a co-pilot on a number of fixed-wing and helicopter models had anything to do with Travis' wish to become a Soldier.

"I never encouraged him or discouraged him from serving," he said. "It would have to be his decision and his alone to make."

At the time, the nation was not at war. But a year later that would change, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Travis steeled himself for the fight he certainly knew he'd soon be in, Jack said.

FIRST IRAQ DEPLOYMENT

Travis deployed with the 101st to Kuwait in early March 2003 and participated in the invasion of Iraq as a fire team leader and later as a squad leader.

One of the many actions that stood out in Jack's mind during his son's deployment was the clearing of a mosque, which terrorists were using as a base of attack.

Travis came face-to-face with a 6-foot-tall Iraqi man and physically took him down. Travis was only 5-foot-7. "He wasn't the biggest guy in the world but he was tough," Jack said. "The Army taught him that."

In less than three years' time, Travis made sergeant. Jack said it was because he was very competitive and competent and had all the markings of an outstanding leader.

He wanted to join the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment in Alaska, after returning from Iraq, but he was told no slots were available, his father said. So he decided to get out.

In December 2003, he was discharged and returned to Montana to continue doing the blue-collar-type jobs he'd previously been doing. He also attended the University of Montana in Missoula.

However, Travis soon began to miss the challenges of military life, his father said.

"I told him he'd paid his dues with the 101st in Iraq, but he wanted to go back in. That's where he felt comfortable," Jack said. "Since he insisted on going back in, I suggested he change his MOS to something he could use when he got out, but he insisted on infantry only.

"The military isn't suitable for everyone, but it was his niche. He belonged," Jack added.

So, in December 2005, he re-enlisted and the Army let him keep his former E-5 rank.

He was assigned to Alpha Co., 2nd Bn., 14th Inf. Reg., 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Div. (Light Infantry), at Fort Drum, New York.

Travis thrived, Jack said. He focused on keeping his young Soldiers well trained.

"Some of them later came to me and said that he was really hard on them and they didn't like it," he said. "But over time, they said they came to appreciate what he did and that hard training in some cases saved their lives."

Travis knew another deployment to Iraq or possibly Afghanistan was inevitable, Jack said.

SECOND IRAQ DEPLOYMENT

Travis was subsequently reassigned to Delta Company in the same battalion and got orders to Iraq again in August 2006.

"I'm not too sure I can make this one," Jack said his son told him. "Travis knew the reality of serving in Iraq. He knew there'd be danger."

Jack and Elaine attended the big deployment ceremony at Fort Drum. "As I looked out over the formation from the viewing stand, I realized that some of them were not coming back," Elaine said. "But you hope for the best."

Similar to his previous deployment, Travis displayed great leadership qualities, this time as a squad leader, Jack said. "His world revolved around his troops, whom he called 'my Joes.'"

When his platoon sergeant went on leave stateside, Travis was elevated to that position and promoted to staff sergeant on May 1, 2007.

On the morning of June 1, hours before he would be going on that search mission, Travis called home, Elaine said.

"He asked me if I'd received the Mother's Day card he mailed," Elaine said.

"No I didn't, I told him."

He then became very apologetic, she said.

Elaine told her son not to worry and to just focus on his mission. She was sure the card would eventually arrive.

THE ENGAGEMENT

When Atkins attempted to search the suspect, the man resisted. Atkins then engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the insurgent, who was reaching for an explosive vest under his clothing, according to an award citation.

Atkins then grabbed the suicide bomber from behind with a bear hug and slammed him onto the ground, away from his Soldiers. As he pinned the insurgent to the ground, the bomb detonated.

Atkins was mortally wounded by the blast. With complete disregard for his own safety, he had used his own body as a shield to protect his three fellow Soldiers from injury. They were only feet away.

Soon after, another insurgent was fatally shot by one of Atkins' Soldiers before he could injure anyone.

LEADER PERSPECTIVES

Owen Meehan, the company first sergeant, said he spoke with Atkins 30 minutes before. They conversed about route security and the placement of the gun trucks in his sector.

The highway they were clearing was known as Route Caprice, a supply route that connected Camp Stryker with other forward operating bases in the vicinity of Baghdad.

Meehan said he was visiting the platoon sergeant of another sector when he heard the explosion. He said he immediately went there.

"His platoon was devastated," he said.

"His men loved him," he added. "He was a damn good NCO and he really, really took care of his men. He was one of the good ones."

Meehan admitted that he "was a little bit of a rough and tough first sergeant," and gave praise sparingly, meaning that he thought Atkins was exceptionally good.

Atkins' company commander, Alex Ruschell, said "he was a phenomenal NCO and monumentally inspiring."

Ruschell, now a major working in the Pentagon, had been with a mechanized unit just prior to this Iraq deployment and Atkins, along with the first sergeant and other NCOs, helped him with the transition to light infantry.

At least several times a month, Ruschell said he thinks about Atkins and his sacrifice. Later, he said he met Trevor Oliver, Atkins' son, and he keeps a picture on his dresser of Delta Company's 2nd Platoon, with Trevor up in front of the guys. He said his own son is about the same age as Trevor.

Former Capt. Clint Langreck, Atkins' company executive officer, recalls him as being "the real deal. He certainly was mature in the way he handled himself and the way he handled troops. I don't remember a day when he wasn't positive or professional. And, he always had a military bearing."

In one engagement, during a route patrol, Atkins' Humvee, which Langreck thinks was the lead vehicle, hit a mine, blowing the whole front end skyward, fortunately not killing or injuring anyone, but destroying the vehicle.

After the explosion and the emotional event, Atkins "had the sound mind to immediately assign sectors and put in security."

In another incident, later in the deployment, the company was conducting a patrol through a small village when gunfire erupted.

"I remember him doing all the right things," Langreck said.

"It turned out to be just some locals probably hunting birds," he said. Atkins' "guys were all postured and ready to shoot and he de-escalated the situation and took care of it all," meaning no Soldiers fired weapons.

After the patrol, Atkins sat down with his men and did an after-action review. "That was the exact right thing to do," he said. "You talk about the situation and learn from it. It left an impression on me watching that."

Command Sgt. Maj. Roberto Guadarrama, Atkins' platoon sergeant then, had served with him during the deployment and for many months before the deployment and got to know him on a personal level.

"We shared a lot of time together," he said. "He was very passionate with the stories he would share about his son, his father, his mother, his hunting trips, his times on the river."

Atkins was also "a great team builder, very competitive, a great person to be around. What a complement he was to the outfit," Guadarrama said.

He was decisive and fluid in his leadership role in critical combat situations where most people would falter or buckle, Guadarrama added. And, his decisions and actions were always correct. He embodied Army values to the fullest.

"I can't speak for everyone," he said, "but I know that the day he was killed, I think a good part was killed inside everybody."

THE MEN ATKINS SAVED

Then-Pfc. Michael Kistel was the driver of Atkins' Humvee. As such, he was with him all the time, including when the vehicle was destroyed by a mine.

When Atkins was killed, Kistel was just a few feet away, on his way to help take down the terrorist. Atkins' body shielded him and the other two Soldiers from the blast. However, the blast from a second terrorist moments later sent fragments into his body resulting in 100 percent disability and a discharge from the Army.

Kistel noted that another Soldier, Spc. Travis Robertshaw, was firing rounds into the terrorist, but he just kept coming. Kistel said he thinks the terrorist must have been on drugs and impervious to the pain.

"We really loved Travis, even though he could be demanding at times, but it was always for our own good," Kistel said.

Today, Kistel lives with his 94-year-old grandmother and his beloved service dog in Tampa, Florida.

The second man saved by Atkins was Robertshaw, a medic. He said he rode in the vehicle with Atkins for several months and knew him very well.

"I remember him as being very intense," he said. "He loved the Army. He loved his country. He was very passionate about the Army and always wanted to make sure the job got done well. But at the same time when we weren't doing Soldier tasks and sitting around waiting, he'd like to joke around, tell stories and just talk to us."

Robertshaw said he now tries to avoid thinking about his time in Iraq, but he's deeply grateful for what Atkins did on his final day and all of the other days he was with him.

Today, Robertshaw is still in the Army, a sergeant first class, serving at Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. He's the NCO in charge of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine.

Then-Spc. Sand Aijo was the third Soldier whose life was saved by Atkins. As the gunner manning a 50-caliber machine gun in the Humvee, he was with Travis almost all the time during the deployment.

"He always put us above everything else. That's the kind of person he was," Aijo said, comparing him to "a tough big brother."

"He could be really strict and tough, but in moments that happened, you came to realize why," he added.

Regarding the day Atkins was killed, Aijo said, "I think about that day all the time. I think it's always important to remember that sacrifice. And, I always try to make sure I live my life to the fullest and do the best I can to make sure that sacrifice wasn't for nothing."

Aijo currently lives in Dallas and works in a project management office for a major financial institution. He used his GI Bill benefits to study business and finance.

NOTIFICATION AND AFTERMATH

On June 1, 2007, a sergeant first class in uniform and an Army chaplain in civilian clothes arrived at the Atkins home in Bozeman to inform the parents that their son had been killed.

Trevor, who was 11 at the time, said, "It was five days after my birthday," mentioning that his dad had called to wish him a happy birthday.

His father's death was hard on him -- still is, he said, particularly around the holiday times. Trevor, who is now 22, recalled Thanksgivings when his dad would peel the skin of the turkey as that was his favorite part. He also fondly recalled their camping, hunting, fishing and snowmobiling trips with his dad and grandparents.

Soldiers from Travis' unit were very supportive, Trevor said. They invited him and his grandparents to Fort Drum, where Trevor said he got to do some cool stuff like driving a Humvee through the forest.

That helped to ease the pain somewhat, he said.

Another thing that helped was getting a call from President Donald J. Trump recently, informing him that his father would be receiving the Medal of Honor. Trump was very cordial and upbeat, Trevor recounted, adding that he complimented him on having good genes from a tough warrior. "That meant a lot to me."

There were other things that eased the pain somewhat, Trevor said.

Battle buddies who had served with Atkins told Trevor how much his father had inspired them and kept them alive through rigorous training. "They treated me so good. That was very, very sweet of them," Trevor said.

One day while fishing, his father had told Trevor to observe how the water was flowing over the rocks and boulders. See how the water is moving and flowing past the obstacles, he pointed out, telling his son that's what he needs to do. Keep moving past the obstacles no matter what.

Atkins was the "best father a son could hope to have," Trevor said. "He was also the best Soldier and leader. I wish I'll be half the man he was and hope to do him proud."

Related Links:

Valor: Above and Beyond the Call of Duty

Social Sharing