FORT MEADE, Md. -- Lt. Gen. Leslie Smith faced the pivotal moment of his life as a 5-year-old child growing up in Atlanta.

His father had fallen ill with liver disease. At the time, Calvin Smith had worked as a teacher and his illness took a heavy toll on the Smith family. He eventually passed away, leaving behind Smith's pregnant mother, Lillie, and their two children. In the years that followed, Leslie would learn the importance of community and having a nucleus of support for him and his siblings.

To shield themselves from racial prejudice during the civil rights era, African Americans often would need to depend on one another, Smith said. Community programs including the Boys and Girls Clubs, Boy Scouts and local churches would provide much-needed safe havens for black children in the American South.

Smith came of age during tumultuous times in the 1960s and 1970s as race relations remained tense in parts of Atlanta. Much of the South still rocked with political turmoil and violence. Smith learned the value of hard work then, knowledge that would eventually follow him into a long Army career.

His military career spanned three decades, eventually landing him the position of inspector general of the Army in February 2018.

DELTA JEWEL

The roots of Smith's ascension in the Army can be traced 400 miles west of Atlanta, to Mound Bayou, Mississippi, a small farming community entrenched deep in the Mississippi delta.

Founded in 1887 by free slaves on swampland just east of the Mississippi River, the town is the nation's oldest predominantly black settlement.

Nicknamed the "Jewel of the Delta," the working class city fostered ample socio-economic opportunities for the Smiths and other hardworking African Americans. The town had defied the odds, forming a prosperous black community at the height of racial segregation in the Deep South.

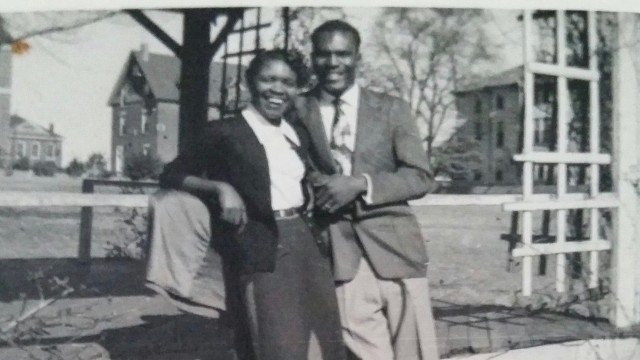

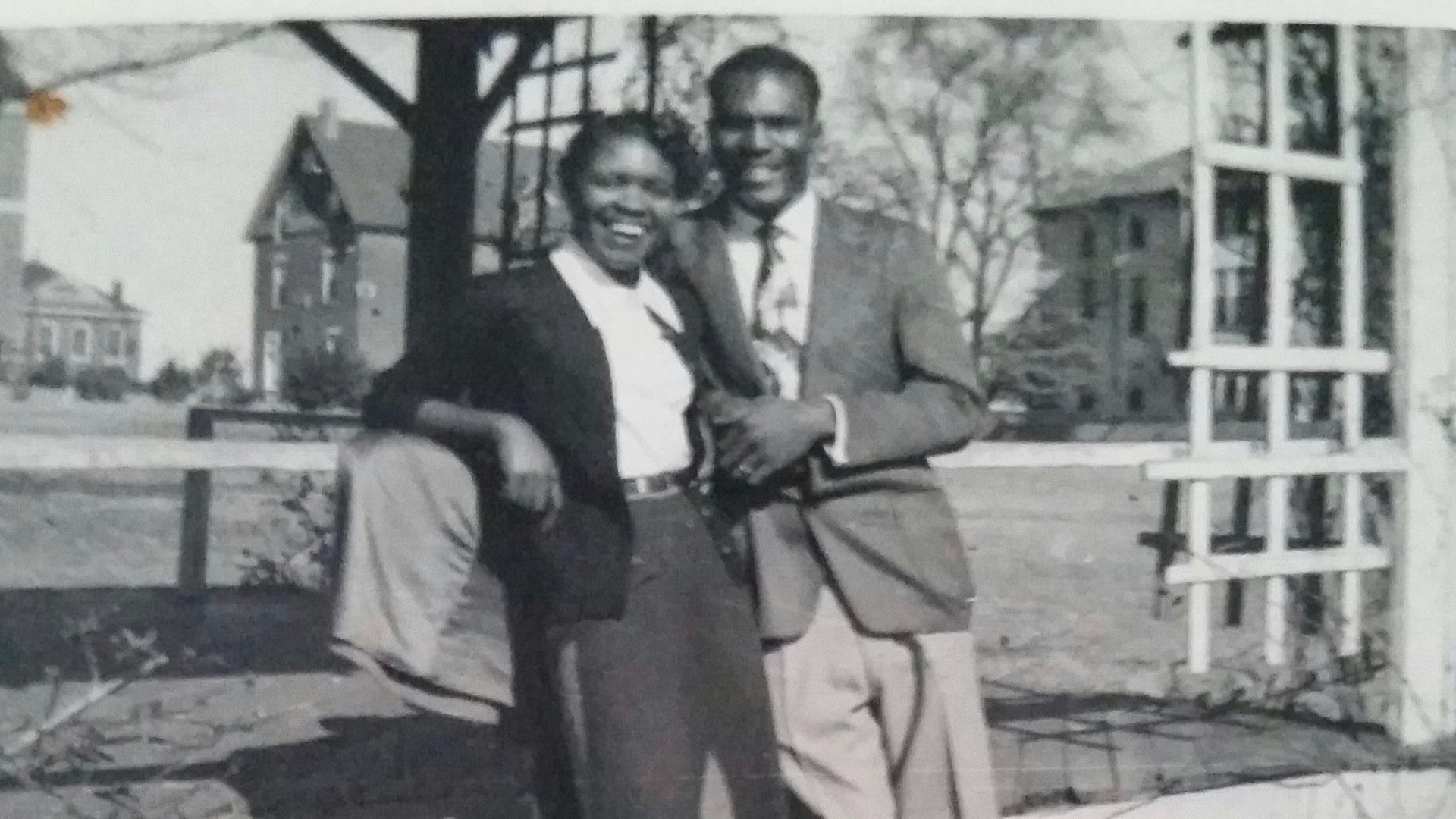

Mose and Rosetta Smith didn't have much money or education. The Smiths made a modest living growing corn, sweet potatoes and soybeans on their 40-acre farm in Mound Bayou. They raised their 10 children: Smith's father and his uncles and aunts -- on the belief that hard work made career aspirations limitless.

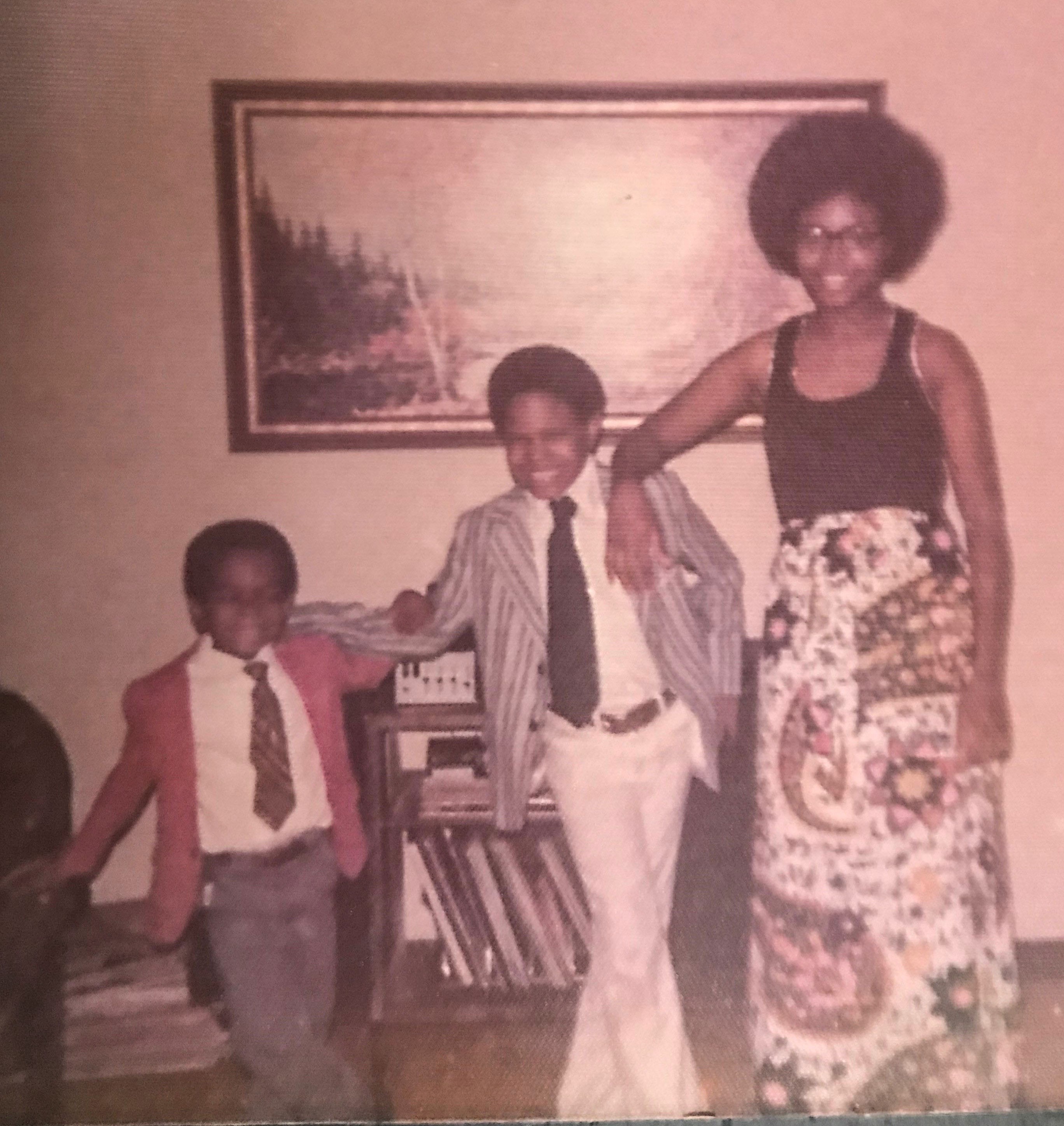

Their grandparents' worldviews left a lasting impression on Smith and his brothers and sister.

"They didn't have a lot of money," said Smith's older sister, Lola Burse. "But what they had was a burning desire for their children to do well."

Eventually, one of the Smith's sons, Calvin, moved his family out of Mound Bayou, to pursue opportunities in the metropolitan sprawl of Atlanta. There Calvin and Lillie planned to raise their children.

LASTING LEGACY

While Smith remembers little of his father, his sister can vividly recall the day their father passed. She cried incessantly in her bedroom when she learned the tragic news.

"It was a very hard time," Burse said. "I had to grow up quickly."

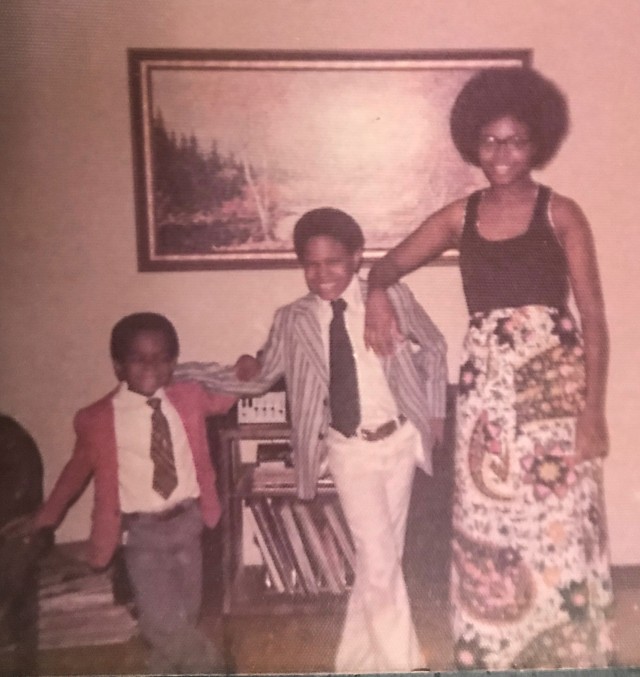

Their mother had to raise three children seemingly alone.

But family members rallied to help raise the Smith children.

As young black men, Leslie and his younger brother Lawrence turned to their uncles for advice. Smith's teachers at Frederick Douglass High -- both black and white -- encouraged Leslie to dream big. They told him he could pursue any career -- regardless of skin color.

But most importantly, the family achievements showed Leslie a black person could succeed even during adverse times.

"I don't know what I missed," Smith said of growing up without a father. "But I always knew who I was and what I am. The circumstance that you came from does not determine where you're going to go."

Curtis Smith provided a steady example. He started working as a barber in Mound Bayou, then opened a grocery store and later, a diner.

"I didn't understand what it meant not to be around strong, black people," Smith said. "Because that's what I saw."

Lillie never complained and worked three jobs at times to put her children through private Catholic elementary schools, giving them a head start on high school academics. She worked as a bank teller and also went door-to-door selling encyclopedias to put her children through private Catholic school.

"I think our family work ethic certainly is something that (Leslie) learned through her example," Burse said.

As part of his development as a young man, Smith worked for a janitorial service travelling to different city blocks in Atlanta in the evenings.

"My mom not being afraid to put us in different (challenging) situations caused us to grow," Smith said.

As he played sports and participated in Boy Scouts activities, he stared in awe at the photo of his late father in his Army uniform. His aunts told him stories of his father's service during the Korean War, and his uncle Terry McCoy's four years as an Army military policeman. Smith's uncle, Nathaniel Smith, also served in the Navy. Another one of Smith's uncles, Joseph Smith, earned a PhD from Rutgers and eventually led the Alcorn State University Math and Science Department. Smith learned his father and uncles needed to work twice as hard to earn the respect of their peers. Integration of black troops in the U.S. military didn't begin until 1948.

"Growing up, my uncles encouraged me to consider military service as a positive way to prove my worth as an adult, and to serve as a role model for others within the community," Smith said.

Smith didn't know the true calling of the military until he met Sgt. 1st Class William Saunders while attending Georgia Southern University. Saunders was a Vietnam-era veteran and ROTC instructor who "identified potential in his cadets from the very beginning, pouring his heart and soul into each of them," while preparing them to serve as officers, Smith said. From Saunders, Smith learned about the career opportunities available through the ROTC program. It would eventually land him positions in field artillery and as a chemical officer.

The support of their family and community strengthened and empowered the Smith children to develop high self-esteem, and to value people of diverse backgrounds, despite the segregation and racial tension that plagued much of American society.

"The opportunities were there," Smith said. "All we had to do was take advantage of them."

That didn't mean they escaped the turmoil completely.

Lillie kept her daughter from using public bathrooms during road trips through Mississippi. Burse learned later her parents didn't want her to see the bathrooms designated for white and black people. She filled her room with stuffed animals, as toy companies did not make brown-colored dolls at the time. Unlike Leslie and Lawrence, Burse was born in Mississippi.

"In the South, especially places like Mississippi, you were required to do things that white Americans were not required to do," Burse said.

For example, Smith's parents had to take a literacy exam and pay a poll tax in order to vote, Burse said.

While some high-profile military officers remain guarded about their past, Smith openly speaks about his. Smith will tell students at elementary schools, high schools and universities about his humble beginnings and how he began working at age 13, hired by the pastor to rake leaves at his local church on Atlanta's west side.

Smith said racial identity never became more apparent than after the death of Dr. Martin Luther King in April 1968. Smith attended the same school as two of Dr. King's children, Frederick Douglass High School in western Atlanta.

After joining the National Guard while attending Georgia Southern's ROTC program, a special program helped grant Smith the distinction of a commission into the Army after only two years in school. He eventually completed a bachelor's degree in accounting in 1985 and went on to earn two master's degrees.

Smith's 32-year military career includes becoming the first chemical officer to command the U.S. Maneuver Support Center of Excellence at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri and the 20th Chemical Biological, Nuclear and High Yield Explosives command in Aberdeen, Maryland. He also had stints as commander of the 83rd Chemical Battalion, and the 3rd Chemical Brigade at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. Meanwhile, his sister Burse had enlisted in the Marines, serving the Corps as a communications troop and later spending two decades working in education. Smith's younger brother later commissioned into the Army as a logistics officer and serves today as a successful businessman in Orlando, Florida.

GIVING BACK

The lessons Smith learned as a youth haven't left him. Now in a senior leadership role under Secretary of the Army Mark Esper, Smith notes the importance of providing young students of all backgrounds the opportunities afforded to him.

Despite a very busy calendar, he still makes time for speaking engagements with students and cadets. He recently mentored African-American high school students at the annual Black Engineer conference in Washington earlier this month. He uses his own career to show students an example of what they can achieve by embracing the pursuit of excellence and commitment to selfless service.

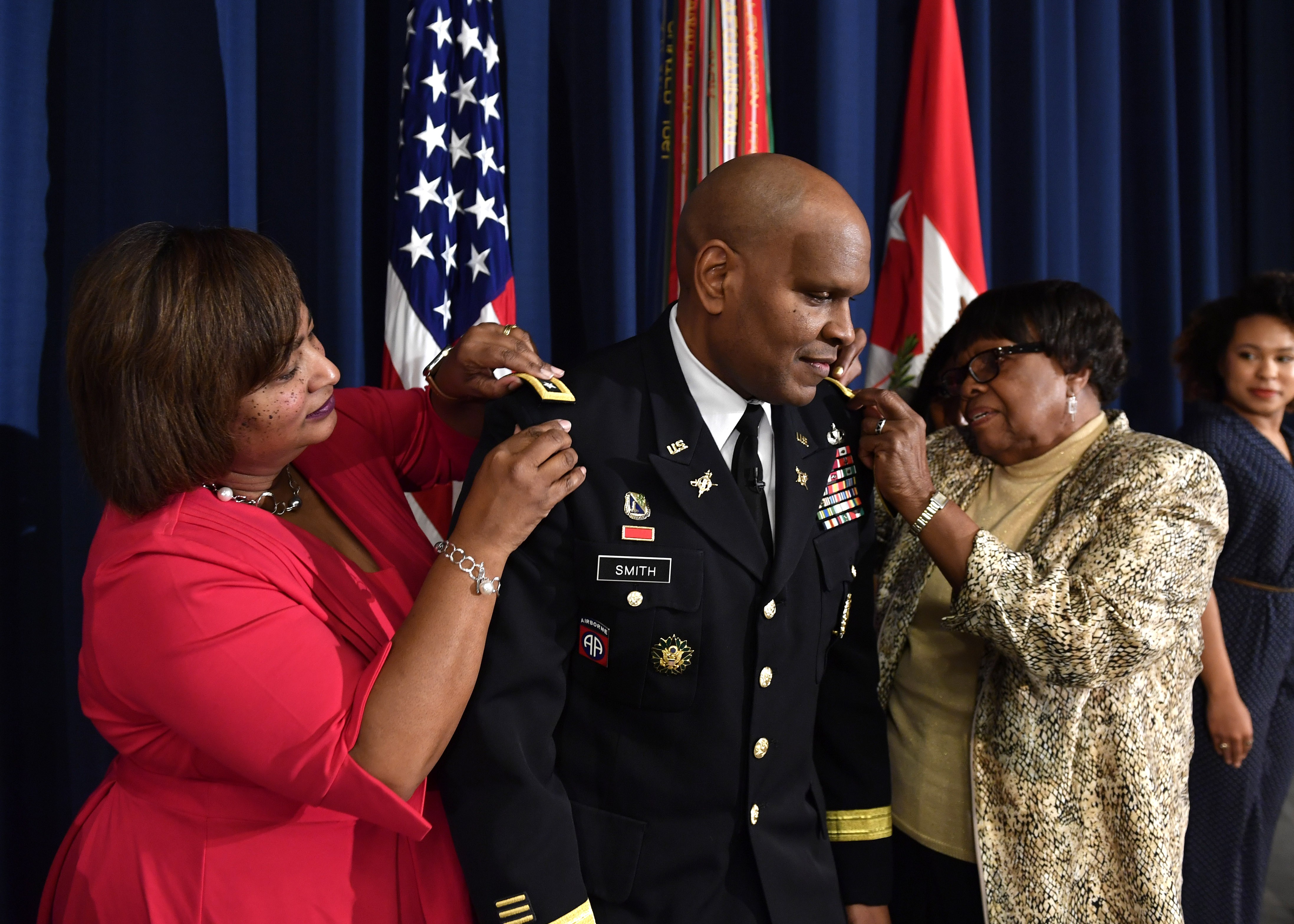

At his promotion ceremony to lieutenant general a year ago, Smith's mother Lillie and his wife, Vanedra, pinned on his new rank at Fort McNair, in Washington, D.C. Smith considers it an honor to have his family's support during promotions and other special events. He also preaches the value of community and the important role that leaders play in communicating with youth about opportunities for military service.

"He's never forgotten about our family's beginnings in a very small town in Mississippi," Burse said. "And that nucleus of family support and strong belief in God."

Being surrounded by strong leaders within his family and his local community helped the general to survive the loss of his father due to illness at an early age. He emerged from the tragedy with life-long lessons on endurance and resilience that he has had the privilege of sharing with young people, including his own daughters, Taylor, an advertising major working in Austin, Texas, and Torrie, a GS alum pursuing a doctorate degree.

"People have to be invested in the next generation," Smith said. "The military teaches us the importance of shaping our environment."

Social Sharing