FORT SILL, Okla. (Feb. 21, 2019) -- Note: This is the last article in a three-part series.

Saving the townspeople of Nogales, Ariz., from ruin was only one of Henry O. Flipper's adventures as he sought to restore his good name during the last 58 years of his life.

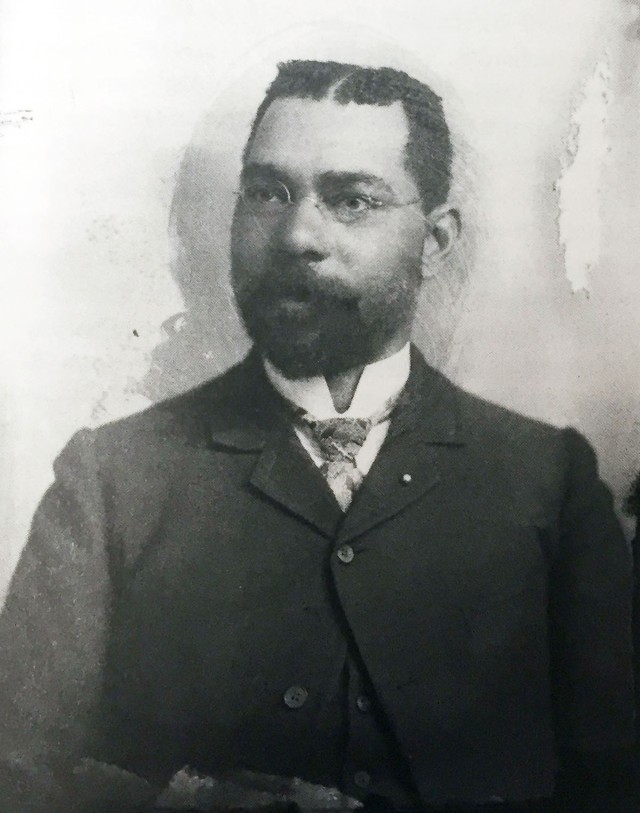

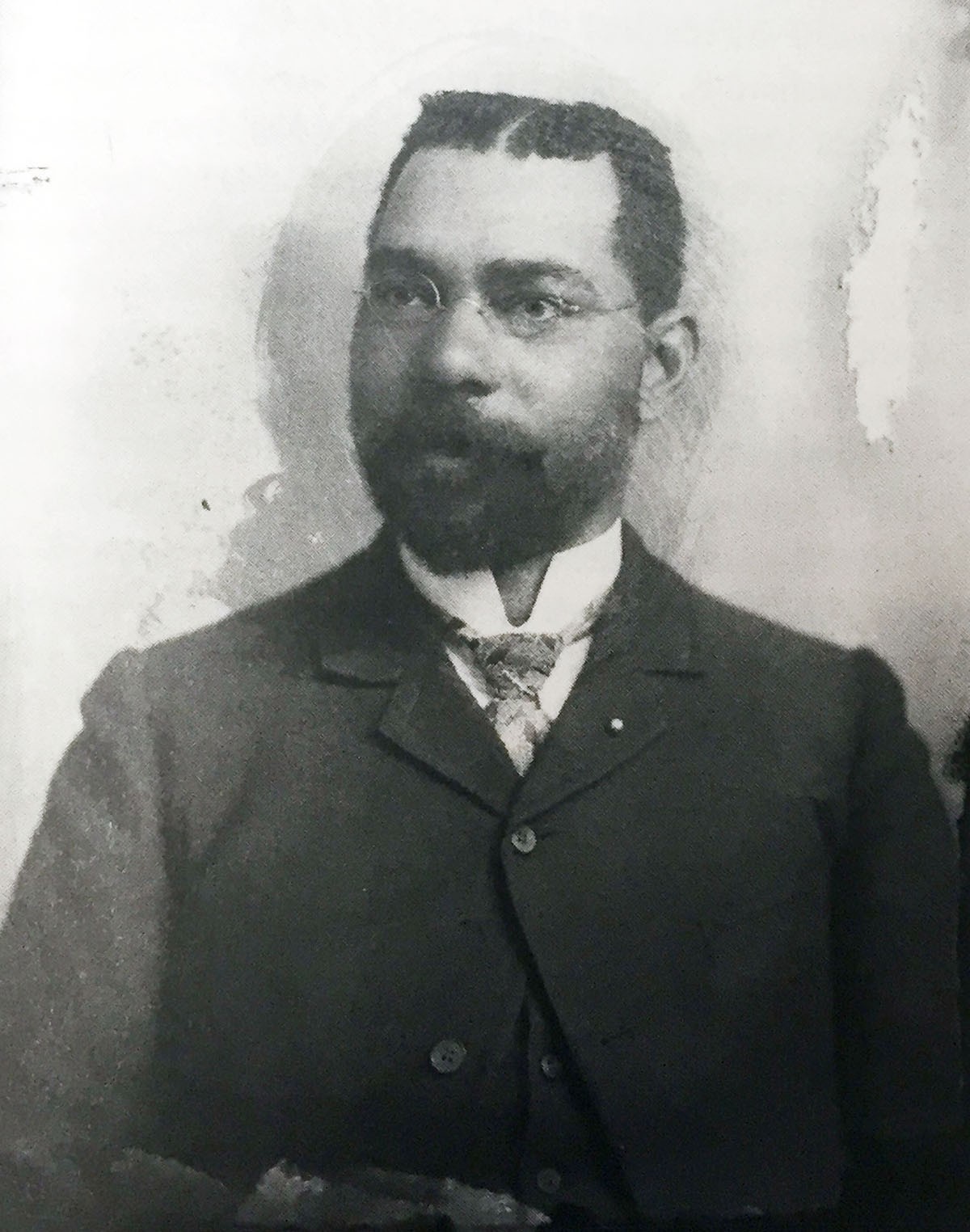

As the first African American to graduate from West Point, Flipper had been a symbol of black achievement.

Following his court-martial and dismissal from the Army on June 30, 1882, the 26-year-old Flipper was now being pilloried in the press as an example of personal disgrace.

He made a deliberate choice not to return east where rigid racial segregation prevailed. Instead, he set out alone for El Paso, Texas, where he would be able to seek his fortune in what historian Theodore D. Harris calls a "socially indulgent and ethnically diverse southwestern borderlands."

In 1883, he left El Paso to work as an assistant engineer for a surveying company of former Confederate officers. Engineer A.Q. Wingo, whom he had met surveying in various parts of Texas when Flipper was scouting with the Army, was the one who insisted on Flipper becoming his assistant. When some whites objected because of Flipper's race, Wingo told them to send Flipper or find someone to take Wingo's place.

"I was hurried down to him without any more ado," Flipper wrote in his memoir.

Flipper assisted the company in surveying public lands in Mexico and helped run a boundary line between the states of Coahuila and Chihuahua in 1883.

The Army provided him the training to become an expert surveyor in mapmaking, and engineering, but now he would pick up new skills. He grew proficient in both written and spoken Spanish, and he eventually became a legal authority on Spanish and Mexican land and mining law.

"To this he added a scholarly competence and originality in research and writing in the history of the Spanish Southwest," Harris states.

Between 1883 and 1891 Flipper worked in Chihuahua and Sonora as a surveyor for several other American land companies.

By dint of perseverance, physical endurance, high intelligence, and meticulous performance of duty, Flipper would become the first black American to successfully forge a career in mining and civil engineering. He opened his own civil and mining engineering office in Nogales in 1887.

In 1891, the town retained Flipper to prepare the Nogales de Elias land grant case for trial. This was a dispute over title to the San Juan de las Boquillas y Nogales land grant in Cochise County, Ariz.

Flipper's work in the Nogales case led to his appointment as special agent of the newly-created U.S. Court of Private Land Claims in 1891. This court was established to decide land claims guaranteed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in the territories of New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, and in the states of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming. As special agent he worked on court materials, served as an expert on penmanship, and surveyed land grants in southern Arizona. He was the principal assistant to U.S. attorneys in the preparation of numerous large federal land claims cases, and he served in this capacity until 1901.

In 1892, he compiled and translated "Mining Law of the United States of Mexico and the Law on the Federal Property Tax on Mines."

The Nogales case went to trial in 1893. Flipper was the only person to testify for the federal government, and by his expert knowledge of Spanish land-grant law he helped prove the legality of the Nogales city charter. The land grant was declared invalid, and the ruling saved the property of hundreds of landowners.

Afterward, the community held Flipper in such high esteem that when James J. Chatham, owner of the Nogales Sunday Herald, left town in the spring of 1895 on political business, he named Flipper to serve as editor of the paper for four months.

"The American people were unaware of it, but Henry O. Flipper had become the first black editor of a white-owned newspaper in Arizona and, perhaps, in America," Harris writes.

That same year, the U.S. government published his translation of "Spanish and Mexican Land Laws: New Spain and Mexico." Flipper also published articles in Old Santa Fe, forerunner of the New Mexico Historical Review.

In 1896 he published a monograph in Nogales entitled "Did a Negro Discover Arizona and New Mexico?" Harris describes this as a study of the role played by Estevanico in the Marcos de Niza expedition in 1539. It included the first English translation of Pedro de Castaneda's account of the expedition and primary research of Flipper's own.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898 the 42-year-old Flipper offered to serve, but bills to restore his rank died in committee in both houses of Congress.

Beginning in 1901 Flipper spent 11 years in northern Mexico as an engineer and legal assistant to mining companies. He joined the Balvanera Mining Company in 1901 and remained as keeper of the company's property when it folded in 1903. Flamboyant mining tycoon William C. Greene bought the company in 1905, renamed it the Gold-Silver Company, and placed Flipper in the legal department, where he handled land claims and sales and kept mining crews out of trouble with the local authorities.

In 1908 Albert B. Fall bought out Greene to form the Sierra Mining Company and retained Flipper in the legal department.

On one of his jaunts south of the border in 1889, Flipper had visited the city of Hermosillo. There he stumbled across a reference to the fabled lost Spanish silver mine of Tayopa, and he was hooked on the subject from then on. It was through his researches as to the whereabouts of Tayopa that he first came to Greene's attention.

TRIP TO SPAIN

Greene and publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst eventually sent Flipper all the way to Spain in May 1911 to scour the Spanish historical archives for hints as to Tayopa's location. Flipper regretfully had to report that the only thing his researches there yielded was a traveling direction. Still, Texas folklorist and historian J. Frank Dobie, author of "Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver," thought Flipper "a remarkable character" who had come closer than anybody to finding the lost mine.

In 1912 Flipper moved back to El Paso, and in 1913 he began supplying information on conditions in revolutionary Mexico to U.S. Sen. Fall's subcommittee on Mexican internal affairs.

In 1916 Flipper got a lesson in "fake news" when a Washington, D.C., newspaper falsely reported him to be serving with the forces of Pancho Villa in Mexico. Justifiably incensed, Flipper fired off a letter to the editor of the Washington Eagle recounting the actual details of his career. He ended with this denunciation of the reporter: "From the foregoing, it is evident that the writer of the article, which you have printed, is a conscienceless, gratuitous, malicious, unmitigated liar, whose only excuse, if any be admissible, is his superlative ignorance."

It was that same year that Flipper wrote his second memoir, which opens with an uproarious account of his days at Fort Sill, Indian Territory.

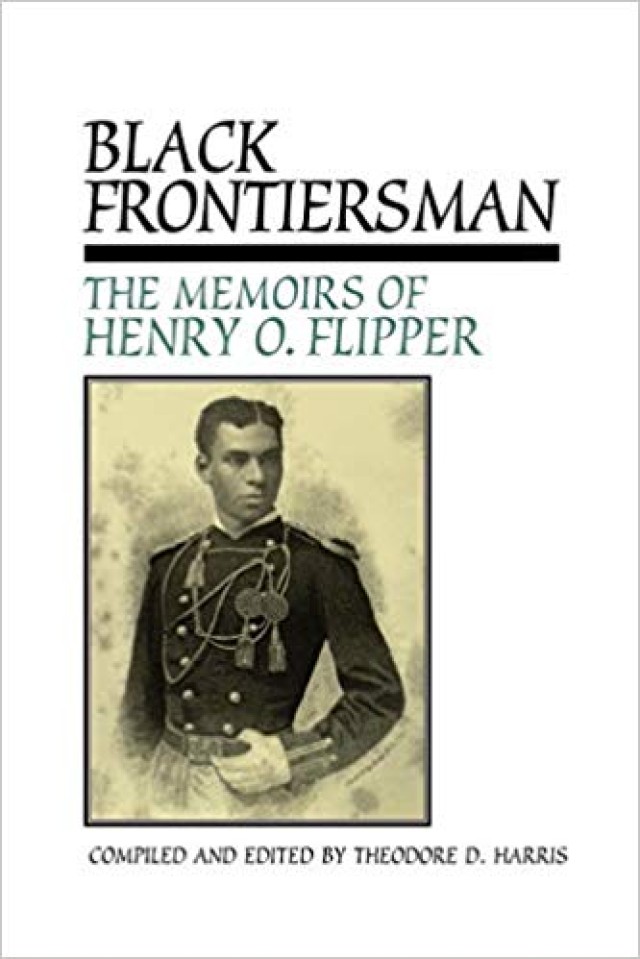

At age 60, he reflects that he has outlived all the white officers who conspired against him at Fort Davis, Texas. Unlike his first memoir, which was published in 1878 while he was stationed at Fort Sill, Indian Territory, this one did not see the light of print until 23 years after Flipper's death.

It was first published in 1963 as "Negro Frontiersman: The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper." The title was modified to "Black Frontiersman" in 1997 when Harris brought out an expanded volume that includes a great deal of additional material.

In 1919 Sen. Fall called Flipper to Washington, D.C., as a translator and interpreter for his subcommittee. Upon his appointment as secretary of the interior in 1921, Fall appointed Flipper assistant to the secretary of the interior. In that position Flipper became involved with the Alaskan Engineering Commission.

He served in the Department of the Interior until 1923, when he went to work as an engineer for William F. Buckley's Pantepec Petroleum Company in Venezuela. In 1925 the Pantepec Petroleum Company published Flipper's translation of "Venezuela's Law on Hydrocarbons and other Combustible Minerals."

Flipper worked in Venezuela until 1930 and retired in 1931. He lived out his life at the Atlanta home of his brother, Joseph Simeon Flipper, a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Henry Flipper died of a heart attack on May 3, 1940. In December 1976, when a bust of him was unveiled at West Point, the Department of the Army granted Flipper an honorable discharge, dated June 30, 1882.

Two years later his remains were removed from Atlanta and reinterred at Thomasville, Ga. President Bill Clinton officially pardoned Flipper on Feb. 19, 1999. An annual West Point award in honor of Flipper is presented to the graduate who best exemplifies "the highest qualities of leadership, self-discipline, and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties while a cadet."

Social Sharing