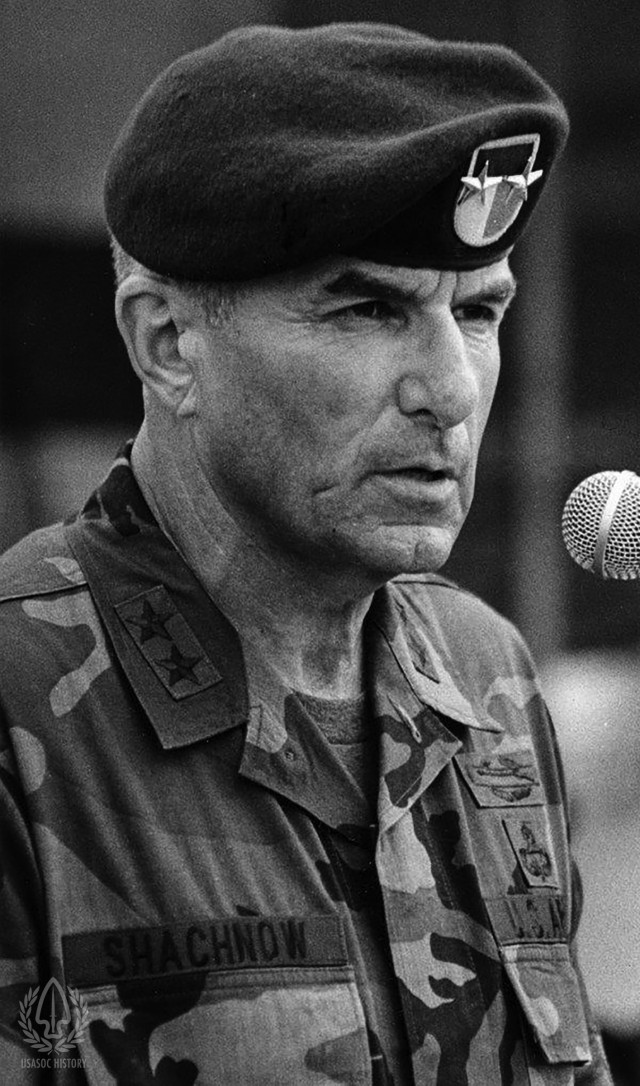

FORT BRAGG, N.C., - Maj. Gen. Sidney Shachnow survived imprisonment, the Nazi Holocaust, and the Second World War to become one of the most influential Army Special Forces officers of the post-Vietnam era. A lieutenant who volunteered for SF in 1963, he commanded at all levels, from detachment to a two-star Army command. During the post-Vietnam era, Shachnow worked with others to establish SF as a branch, building units and commands that are fully engaged today in the campaign against transnational terrorism.

Shachnow was born Schaja Shachnowski in 1934 in Kaunas, Lithuania. Born Jewish, young Schaja lived the horrors of the Second World War first-hand.(1) A year after the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 divided Eastern Europe between the two dictatorships, the Soviet Union invaded the Baltic states, which included Lithuania. Stalinist repression followed, with rigged elections, secret police, political prisoners, torture, and deportations of suspect groups to Siberia. The brutal communist occupation of Lithuania lasted until the Germans invaded in June 1941, making life in Kaunas even harsher for Jewish families.(2)

Schaja, his family, and the entire Jewish population of Kaunas were confined to a ghetto, which was designated Concentration Camp # 4, Kovno. Deprived of food, medical care, and essentials, life in the concentration camp was a daily struggle for survival. Shachnow stole food to help his family. After almost three years in the camp, he was smuggled out to live with a local farming family. His parents and younger brother also escaped; however, of the original 40,000 Jews confined in Kovno, only about 2,000 survived. In August 1944, the Soviet Army reoccupied Lithuania when Nazi forces retreated into Germany.(3)

Shachnow and his family escaped Lithuania shortly after the end of the war. Like millions in Europe, they became displaced persons traveling west toward Germany and the American Zone. In Nuremberg, the thirteen-year-old Schaja worked on the black market. Befriended by an American Army sergeant, Shachnow admired the U.S. Soldiers occupying Germany. In 1950 the Shachnow family immigrated to the United States.

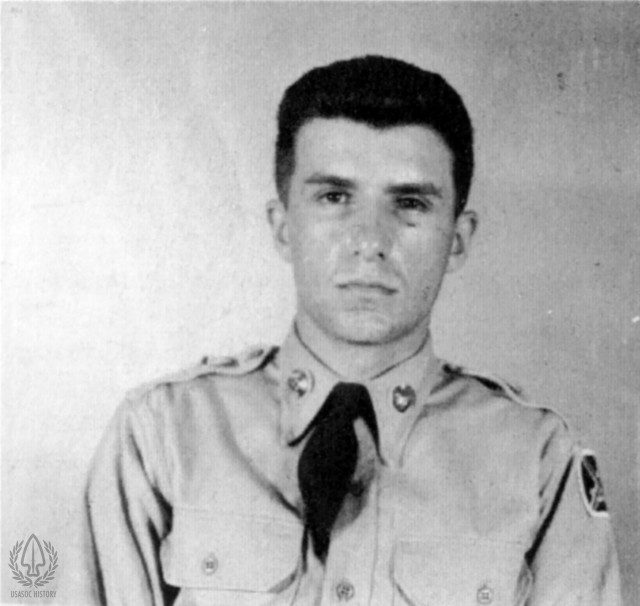

Settling in Salem, Massachusetts, he learned English while working to help support his parents, and attending school regularly for the first time. After graduation from high school in 1955 he enlisted in the Army as an infantryman, with basic and service with the 87th Infantry, 10th Infantry Division, Fort Riley, Kansas, and in West Germany. In 1958 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen, with a formal name change to Sidney Shachnow. He rose through the enlisted ranks to sergeant first class. After completing Ranger School, he graduated from Infantry Officer Candidate School, Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1960, as a distinguished graduate.(4)

Then, it was back to Germany as an infantry platoon leader and company commander in the 4th Armored Division. 1st. Lt. Shachnow finished the Special Forces Qualification Course in 1963, and was assigned to 5th Special Forces Group, Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He deployed to South Vietnam in 1964 as the commander of Operational Detachment Alpha A-12, to organize and train a Civilian Irregular Defense Group near the Cambodian border. During the 1960s, he served in a variety of SF and infantry assignments, and returned to Vietnam to serve with the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile).(5)

Major Shachnow returned to West Germany to command SF Detachment-A in West Berlin. After commanding a mechanized infantry battalion with the 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Hood, Texas, he returned to Fort Benning. There, he was deputy commander for the 197th Separate Infantry Brigade and commander of the Infantry Training Group, a brigade command responsible for all Infantry one Station Unit Training. From 1983 to 1988, he served as the operations, chief of staff, and deputy commanding general for 1st Special Operations Command, Fort Bragg, North Carolina. This five-year period was a critical time, as SF became a Combat Arms Branch, training improved, and the Army established USASOC as a major command. Brigadier General Shachnow helped modernize Army Special Operations before his Pentagon tour as director of United States Special Operations Command, Washington Office. In December 1989 he was selected to be the commanding general for the Berlin Brigade, as Germany reunified.(6)

Promoted to major general in 1991, he returned to Fort Bragg, to command the U.S. Army Special Forces Command, leading the five active duty, two National Guard, and two Army Reserve SF Groups in the aftermath of Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm. The following year Shachnow assumed command of the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg. As commanding general, he reoriented the 'schoolhouse' to produce SF Soldiers with regional orientation, foreign languages, and interpersonal skills. Maj. Gen. Shachnow wanted them fully capable of working 'by, with and through' indigenous forces. Shachnow retired from active duty, October 1994 with almost 40 years of distinguished service.(7)

After retirement from the Army, Shachnow was a senior mentor, guest speaker, and board member for various charities. In 2004 he wrote his autobiography with Jann Robbins entitled Hope and Honor. Shachnow was honored in 2007, as a Distinguished Member of the Special Forces Regiment, and in 2010 was elected as the Honorary Colonel of the Special Forces Regiment. In interviews, he often credited flexibility, tenacity, and assertiveness as keys to his survival of the Holocaust.(8) Shachnow passed away, September 27, 2018, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D. C.(9)

(1) Major General Sid Shachnow (U.S. Army Ret.) and Jann Robbins, Hope and Honor, (New York, NY: Forge Books, 2004), 13-14, and MG Sidney Shachnow Department of the Army (DA) Officer Record Brief (ORB), copy in Classified Files, USASOC History Office, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter, Shachnow ORB.

(2) R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the present, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1986), 1036-1037; Stephane Courtois, Nicolas Werth, Jean-Louis Panne, Andrzej Paczkowski, Karel Bartosek, and Jean-Louis Margolin, The Black Book of Communism, Crimes, Terror, Repression, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 207-212, 236.

(3) Shachnow and Robbins, Hope and Honor, 30-33; Dupuy and Dupuy, The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the present, 1116.

(4) Shachnow and Robbins, Hope and Honor, 123-281; MG Sidney Shachnow DA General Officer Resume of Service Career, copy in Classified Files, USASOC History Office, hereafter, Shachnow Resume.

(5) Shachnow and Robbins, Hope and Honor, 285-308; Shachnow Resume and ORB.

(6) Shachnow and Robbins, Hope and Honor, 351-373; Shachnow Resume.

(7) Stanley Sandler, "To Free From Oppression; A Concise History of U.S. Army Special Forces, Civil Affairs, Psychological Operations, and the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School," U.S. Army Special Operations Command, 1994, 92-96; Shachnow and Robbins, Hope and Honor, 384-390.

(8) "Sidney Shachnow, 83, Is Dead; Holocaust Escapee and U.S. General," The New York Times, October 12, 2018.

(9) SF Distinguished Member and Honorary Colonel of the Regiment listing, U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (USAJFKSWCS) portal, https://usasoc.sof.socom.mil/sites/swcs-swc/sf/SFDMOR/Lists/SFDMOR/AllItems.aspx, accessed February 5, 2019, and "MG Sidney Shachnow, Special Forces legend, Holocaust survivor, has died," The Fayetteville Observer, October 2, 2018.

Social Sharing