In honor of those who served their fellow injured or ill soldiers with compassion and courage while providing medical care, Army Medicine is remembering physicians, nurses and medics to ensure their stories are not forgotten.

Once such individual is Capt. Alvin Vincent Blount Jr.

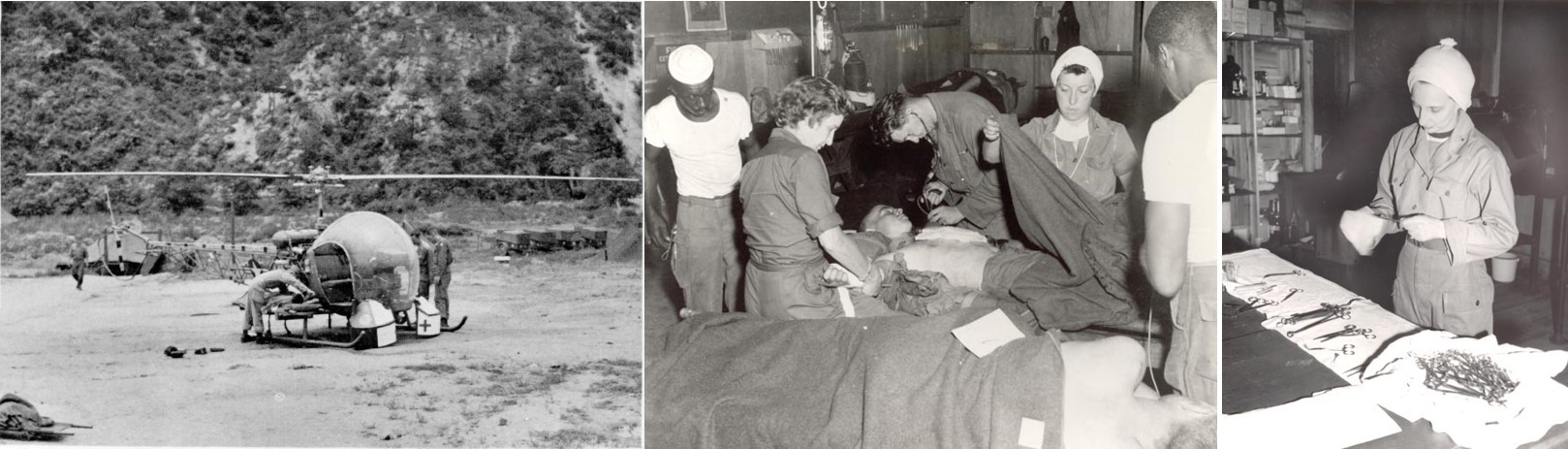

Blount is credited with being the first black physician to serve in a MASH unit or Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. The MASH unit is familiar to most Americans because it was popularized by the M*A*S*H television series.

Blount was the first black to become chief of surgery in a MASH. Two historical factors led to the opportunity for Blount to be a surgeon in a mobile hospital.

One factor was the establishment of the MASH. The MASH concept was developed during World War II. In short, it was a mobile hospital that could be loaded--equipment and personnel--onto trucks. Setup was intended to be fast, even though a MASH unit could have several dozen canvas enclosures, and patients could be accepted within hours of setup.

The second was the integration of the US armed forces followed the signing of Executive Order 9981 by President Harry S. Truman in 1948. In 1951, Gen. Matthew Ridgway, commander of the Far East Command, believed that desegregation was good for morale and began to integrate training. Ridgway was farsighted; his proactive policy helped to create equality of opportunity in the military. Opportunity in the military often preceded that of the private sector in the 1950s.

Blount attended medical school at Howard University during the 1940s in Washington, DC, where he studied under Charles Drew. Drew at the time was a leading medical researcher and also African-American. Drew is famous for his work in the storage and processing of blood for transfusions. He developed large-scale blood banking and managed two large blood banks during World War II.

Blount deployed with the 8225th MASH from Fort Bragg in 1952. The 8225 supported the 1st Cavalry Division from Fort Hood, the 2nd Infantry Division, which was the most decorated division from the Korean War, the 24th Infantry Division from Fort Riley, and the 25th Infantry Division from Hawaii. Blount would earn the Korean War Service Medal for his service as a surgeon.

The 8225 set up about 10 miles from the 38th Parallel. MASH units were usually positioned as close as possible to the front to provide quick access for the wounded to surgical care but beyond the reach of enemy artillery. The 8225 had up to four surgical tables in operation simultaneously, and in a typical week might see about 90 surgical cases. Medical staff of the 8225 deserve great credit for their success rate; during one documented period of 1,936 admissions, only 11 deaths were reported, which is a survival rate of almost 99.5 percent.

During Blount's tour, the chief of surgery became ill and was unable to perform his duties. The MASH commander named Blount chief of surgery during the illness.

After Korea, Blount returned home to set up practice in North Carolina and faced civilian segregation. Most state and local medical societies did not provide memberships to African-American physicians. They had few privileges at hospitals and, especially in the South, could not see white patients. Blount primarily performed surgery at L. Richardson Memorial Hospital. Moses Cone Hospital in Greensboro, which had much superior surgical services, required membership in the county medical society, and from that Blount was excluded.

In the 1960s, Blount became a plaintiff in a historical lawsuit (Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital) that challenged the use of federal funds in a discriminatory manner. The outcome was an agreement with the federal government that changed how public funds were being used in segregated hospitals. Blount eventually became the first African American surgeon to operate at Cone Hospital in 1964.

We remember Capt. Alvin Vincent Blount Jr. for his life-saving contributions to his fellow Soldiers and for his commitment to the Nation by providing medical and surgical care to his community at home. He died at age 94 in January 2017.

-----

Source: Wilson, KL, et al. The Forgotten MASH Surgeon: The Story of Alvin Vincent Blount Jr. MD. Journal of the National Medical Association. 104: 221-223, 2012.

Social Sharing