NASHVILLE, Tenn. -- Innovation is about finding new and sometimes unexpected solutions to complex problems. Soldiers from the 3rd Brigade Combat Team "Rakkasans," 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) have informally teamed up with Vanderbilt University to leverage emerging technologies in innovative ways.

The 3rd Brigade Combat Team fosters a culture of innovation from the highest-ranking officer to the lowest enlisted Soldier. Col. John P. Cogbill, commander of the Rakkasans -- a Japanese word meaning "falling umbrella men," given to Soldiers from the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team during post-WWII occupation -- encourages Soldiers and leaders in the brigade to think critically, collaborate and find creative solutions to complex problems.

Seizing an opportunity to do just that, the Soldiers of Company B "Breacher," 21st Brigade Engineer Battalion, a company in the Rakkasan Brigade, recently worked with the Wond'ry Makerspace at Vanderbilt University to employ 3D printing to fix problems that were historically addressed with little more than 550 parachute cord and 100 mph tape -- also known as duct tape -- common items found in every Army unit and widely on the internet.

INNOVATION IN ACTION

Among the challenges that the Rakkasan Soldiers face is how to sustain operations and maintain readiness in remote and austere environments. During quarterly brainstorming sessions and brigade innovation forums they realized that 3D printing technology could offer materiel solutions to some of these challenges.

They invited Dr. Kevin Galloway, director of making and a research assistant professor in the Vanderbilt University Mechanical Engineering Department, to an innovation event sponsored by the Rakkasans to explore these ideas. In this open setting dedicated to sharing and exploring ideas, Galloway and Rakkasan leaders discussed how to turn ideas into action.

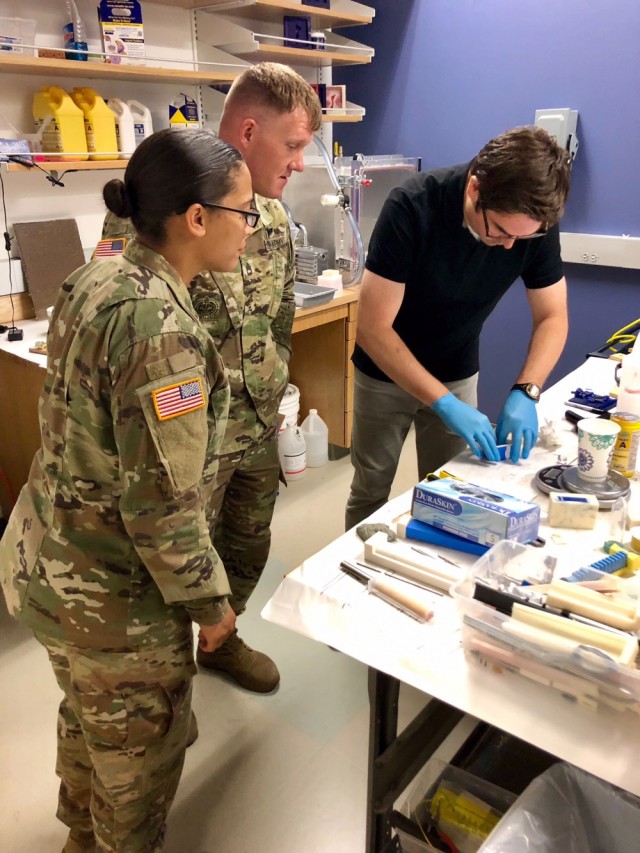

Soldiers from Breacher Company visited Galloway's Wond'ry Makerspace, a state-of-the-art prototyping laboratory with 3D printers, fiber arts, mold-making and casting materials. Breacher Company leaders and Galloway's team had an opportunity to work together to bring concepts to life. "The rapid fabrication tools available today have significantly lowered the barriers to advance innovative ideas," Galloway said in an interview. "With a little technical training, anyone can quickly learn how to harness the power of these tools to validate early stage ideas before more resources are invested."

The Soldiers presented the difficulty of developing easy-to-fabricate and easy-to-use visual marking systems to Galloway's team. Soldiers employ a variety of marking systems as visual signals across the battlefield. These signals help direct traffic, maintain unity and spacing between Soldiers, and, perhaps most importantly, designate safe zones and lanes for weapon systems. The problem the company faced was that its current systems were bulky and not standardized within the unit. For a marking system to be effective, it must be easy to carry and use, and universally recognizable to Soldiers across the entire unit. With Galloway's help, the Soldiers explored ways to develop a standardized marking system.

THE LINKS THAT BIND

Marking systems are more complex than a single VS-17 panel, a cloth marker commonly used to allow pilots to identify friendly units from the air during the day, or a single luminous chemical light during the night. During a recent .50-caliber machine gun training, Sgt. 1st Class Jesse Frederick, a platoon sergeant in the company, was inspired by the links that hold the .50-caliber ammunition in place. He had seen these links used to hold chemical lights together, but realized that they could be welded together to hold multiple chemical lights (of different colors) in a standardized system. Frederick created a prototype of the marking tool he envisioned.

Initially, he molded a rudimentary holder in the shape of two links to house two chemical lights and a grommet to hold a strip of VS-17 panel. There were some initial design flaws in the prototype; the holes were too small and did not push to the middle of the chemical light, and the material was flimsy and would likely break if carried over long distances in a pocket or a backpack. However, with Galloway's help and a little bit of computer-aided design work, a 3D printer was producing a more precise and durable marking system within 30 minutes.

Once the initial product was complete, Breacher Company progressed to the casting and molding room. There they learned how to create silicone molds that could be filled with resin to batch- fabricate holders without the use of a 3D printer. After all, there may not be a 3D printer and a dedicated laboratory in the remote and austere environments where the company may have to operate.

Now, several weeks after that initial visit, Breacher Company has produced hundreds of these systems and can offer the Rakkasan Brigade a standardized and effective marking system for both day and night operations.

CONCLUSION

The marking system is just one of the latest collaborations between the Rakkasans and Vanderbilt University, and more projects are ongoing. "This partnership from the beginning has been very rewarding," Galloway said. "Soldiers have lots of ideas and challenges to share. Creating this opportunity for them to see how the latest technology could be used to advance their idea while creating real-world challenges for students to advance their skills, it's a win-win situation."

The collaboration between the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) and Vanderbilt could serve as a model for the rest of the Army. "This type of symbiotic relationship between tactical units and partner universities could, if scaled, greatly accelerate the velocity of innovation efforts, providing the Army with a more ready and lethal force," Cogbill said. "Formalizing these relationships is exactly the kind of initiative that the Army Applications Lab at the Army Futures Command is looking to facilitate."

Social Sharing