One of the remarkable achievements Ulysses S. Grant is known for even today, are his extraordinary accounts of his life published 1885 after his death, The Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, in two volumes. They are an amazing literary accomplishment but even more so, his candor, honesty and simplicity are breathtaking at times. As a young lieutenant, he formed an opinion about the Mexico-U.S. War 1846-48 that remained with him until his death and echoes down the hall as generations have come and gone.

"For myself," Grant wrote later about the United States war against Mexico, "I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation."

The political, cultural and social era of the 1830s birthed a mission transcribed as Manifest Destiny, America's expansion westward into the lands occupied by native tribes and the Republic of Mexico. This national attitude was a major cause of the war with Mexico and had tragic results for many. Grant, though against the war personally, served to the best of his ability as a matter of duty.

Lieutenant Grant stationed with the 4th U.S. Infantry at Jefferson Barracks, just south of St. Louis in 1843 after graduation, witnessed this national drama of the westward push of a new nation. As events unfolded, America political figures and many citizens envisioned a nation coast to coast, but diplomacy eventually failed and soon war was the result.

For young Ulysses, war and politics was not as important to him as gaining the hand of Julia Dent before he shipped out to Texas in May 1844. Though secretly engaged to Julia, he would not see her for nearly four years. Posted in Texas, he served for one of the great American generals of all time, a leader he would replicate as a role model, Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor, later president of the United States.

The old general seldom wore a uniform and not at all formal, and for West Point graduates accustomed to regulations, parade-ground dress standards and rigid discipline, to see Taylor wearing civilian attire with a large planation hat was indeed strange, but as for Grant, "There was no man living who I admired and respected more highly."

By the spring of 1846, most of the federal Regular Army was in camp at Corpus Christi when orders came to march 130 miles south the Rio Grande. This meant war for the Republic of Mexico. For President James K. Polk, war was justified after all the diplomatic offers and inducements failed because American soldiers were ambushed and killed in the new state of Texas.

For Lt. Grant, this conflict provided a great deal of combat experience, because he fought in every major battle except Buena Vista in February 1847. Assigned as the regimental quartermaster officer of the 4th U.S. Infantry, Grant was responsible for the logistics and transportation needs of a regiment of nearly 1,000 men. He served through the two early battles of May 8-9, 1846, Palo Alto and Resaca del la Palma near the mouth of the Rio Grande. This was Grant's first taste of bloody combat.

By September 1846, Taylor's American army was encircling Monterrey, Mexico. Here, Grant exhibited an amazing feat of courage, amid this hellish urban combat among the narrow streets of Monterrey.

Locked in fierce street by street fighting, Grant was forward with several companies when ammunition was nearly gone. He mounted a horse, kicked a leg over the saddle and hung low on the horse's neck and flank, then raced the animal to the rear. Then after gaining help and ammunition, he returned under intense fire again, being fired at street by street, and amazingly arrived to resupply his regiment unharmed.

He fought in more battles in central Mexico under another American general, Winfield Scott, "Old Fuss and Feathers," who was all spit and polish, ostentatious in dress and manner, and exactly the opposite of Gen. Taylor. Scott and his army made an amphibious assault on the Mexican coast of some 12,000 soldiers in one day with no casualties. Grant was involved in the key victories from Vera Cruz on the coast, Puebla and Cerro Gordo on the advance to the interior, and then the battles in the Valley of Mexico. Resistance stiffened against the American forces as they approached Mexico City, the capital.

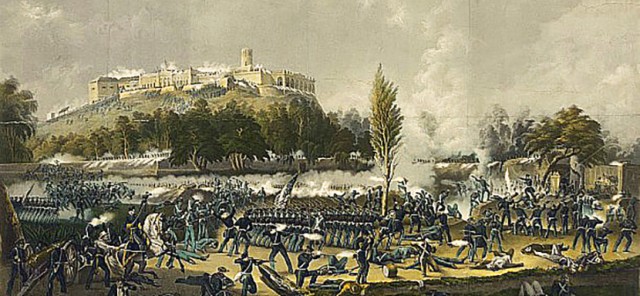

These battles, great and small, surrounding the city with water ways, causeways and canals were like spokes of wheel. During the final assault on Sept. 12, near Chapultepec Castle, Grant was up forward as quartermaster but soon assumed control a dozen soldiers of his regiment.

They were engaged in deadly firefights against Mexican snipers among the arches of an aqueduct. Here, he saw at the San Cosme Gate a nearby church with a tactical advantage. He ordered his men to disassemble a field howitzer and carry it in parts to the top of the steeple, reassembled it, and then engaged the enemy, clearing the gate for an assault and entrance onto a causeway.

Grant received two brevet, honorary, promotions for gallantry from second lieutenant to captain. He would always use both Gens. Scott and Taylor as role models for leadership, though they were totally opposite in manner and style.

(Editor's note: This is the second in a series on Ulysses Grant until his statue dedication at West Point on April 25.) there was ever a more wicked war...I thought so at the time...only I had not moral courage enough to resign."

Social Sharing