FORT MEADE, Md. — The screams of a fellow Soldier trapped inside his armored vehicle pierced through the radio.

Apparently surrounded by the enemy with no more ammunition, the Soldier cried for help saying his crew had all been killed.

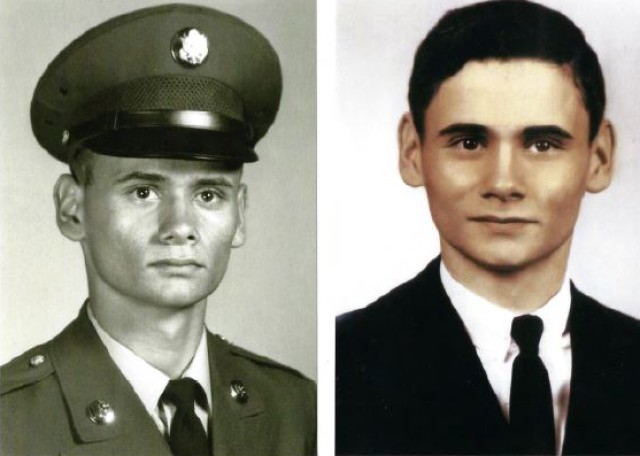

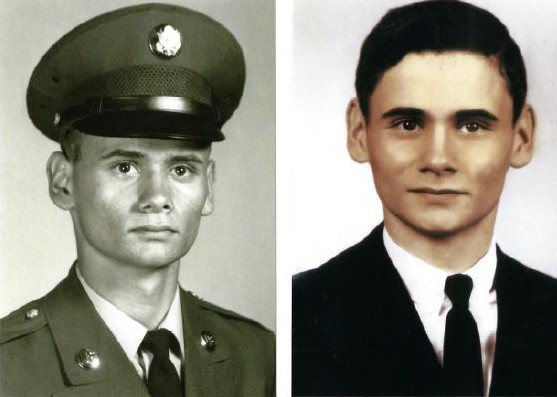

But with his radio keyed open and no one able to talk back to him, then-Spc. 4 Dave Garrod and others in Bravo Troop, 3rd Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, could only listen to the desperate pleas.

"It was a knee knocker," Garrod recalled as his 25th Infantry Division unit raced down to Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which was under siege by enemy forces. "I had no idea what we were driving into."

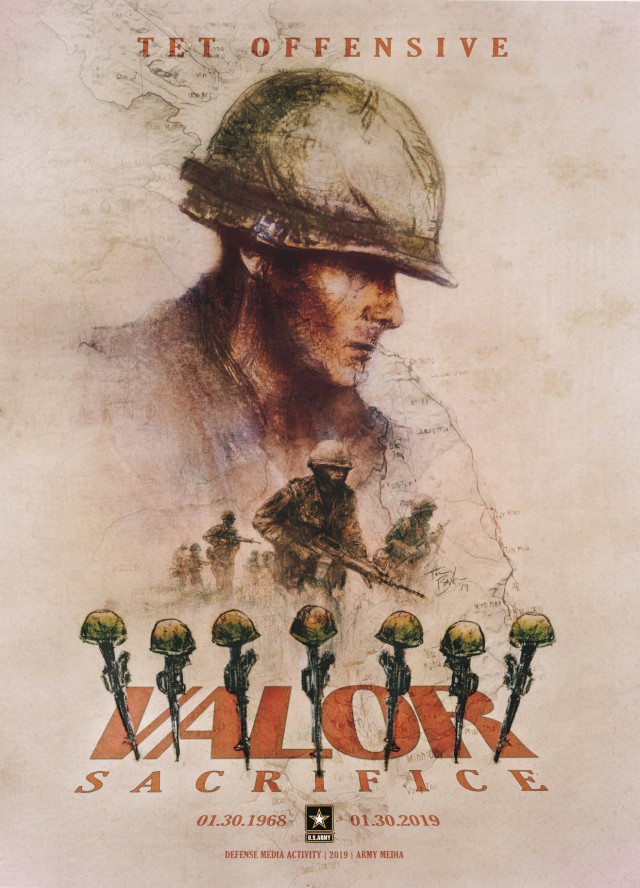

TET OFFENSIVE

On Jan. 30, 1968, the Vietnam War escalated as enemy forces launched surprise attacks during the country's New Year holiday.

About 85,000 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese army fighters rushed across the border to attack over 100 cities and towns in southern Vietnam in an attempt to break a stalemate in the war.

Weeks of intense fighting ensued causing heavy losses on both sides.

Before they could repel many of the attacks, thousands of U.S. and South Vietnamese troops would die. Tens of thousands of enemy fighters were also killed.

While not largely deemed a victory for the enemy forces, which suffered a greater toll, the attacks did trigger many in America to rethink U.S. involvement in the protracted war.

TAN SON NHUT

One of the enemy's main targets was Tan Son Nhut, a key airbase near Saigon where the Military Assistance Command Vietnam and the South Vietnamese air force were headquartered.

After reports of Viet Cong fighters attempting to invade the airbase on Jan. 31, Soldiers with 3rd Squadron's Charlie Troop responded to the call.

As they drove toward the airbase in the early morning hours, then-Spc. 5 Dwight Birdwell remembers seeing no civilians along the highway -- typically a bad omen.

Birdwell had seen attacks before during his tour, he said, but they were mainly mines or other small arms weapons fired by a hidden enemy. This day would be different.

When they arrived just outside the airbase, his unit's column of tanks and armored personnel carriers suddenly stopped.

As if on cue, thousands of tracer rounds began to pepper the vehicles in front of his tank from both sides of the highway. Enemy fighters then jumped onto the vehicles, shooting inside of them.

"All hell broke loose," Birdwell recalled.

A bullet then struck Birdwell's tank commander right through the head and he collapsed inside the tank. Birdwell pulled him out, he said, and passed him over the side for medical treatment, which kept him alive.

Birdwell took command of the tank. By that time, all the vehicles ahead of him had been wiped out or were unable to return gunfire. Enemy fighters also set some ablaze after they failed to drive off with them.

"There was a lot of confusion and pandemonium," he said.

His tank fired its 90 mm cannon toward the enemy while he shot off rounds from the .50-caliber machine gun to hold the enemy back.

Birdwell's unit was stuck in the middle of an enemy invasion as hundreds of fighters had already crossed the highway and penetrated the airbase to his left. On his right side, even more fighters -- some just 50 feet away -- prepared to join the assault.

"They were getting close," he recalled. "I could see their faces quite well."

Around the same time he ran out of ammunition, a U.S. helicopter was hit and made an emergency landing behind his tank.

"I thought that this is unreal," Birdwell said. "Somebody is filming a movie."

He jumped down from the tank and ran toward the helicopter. Once there, he grabbed one of the helicopter's M-60 machine guns the door gunners had been using and returned to his position.

After a few minutes of firing rounds at the enemy, something hit the machine gun -- likely an enemy bullet. The impact, he said, sprayed shrapnel up into his face and chest.

With the M-60 now destroyed, Birdwell said he took cover in a nearby ditch. He and a few Soldiers then grabbed some M-16 rifles and grenades and moved to a closer position behind a large tree.

There, they exchanged gunfire and tossed grenades over the road until the enemy started to fire a machine gun at them.

As the barrage of bullets cut into the tree, it sounded like a chainsaw chewing it down.

"We were in a very desperate situation," he said.

REINFORCEMENTS

Around that time, Garrod's Bravo Troop began to roll into the area.

Soldiers in a different platoon within Charlie Troop also arrived to suppress the attack from inside the base.

"After pulling on line we started laying down fire," Garrod recalled, "and trying to keep it as low as possible so as not to fire on Charlie Troop on the road."

Garrod and other Soldiers were then pulled away to help wounded crewmen near a textile factory from which the enemy had been commanding its attack.

Once there, he ran over to a tank that had been hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. Inside, he could see the tank's loader who could not move due to his legs being seriously wounded.

"Being a small, skinny guy, I jumped down in the hatch and without thinking put him on my shoulders and stuck him up through the hatch," he said.

Later that day, the intensity of the battle hit home for Garrod as he rested in the shade of his vehicle.

He lifted his canteen up to take a drink when an awful smell overcame him.

"When I looked down on my flak jacket, there was a hunk of flesh from that loader," he recalled. "It's something that's etched into your mind forever."

Almost 20 Soldiers from the squadron were killed and many more wounded as they defended the airbase that day. About two dozen South Vietnamese troops were also killed along with hundreds of enemy fighters.

Garrod earned an Army Commendation Medal with valor device for his actions and a Purple Heart in another mission a few days later. Birdwell earned a Silver Star and a Purple Heart.

The squadron was also awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

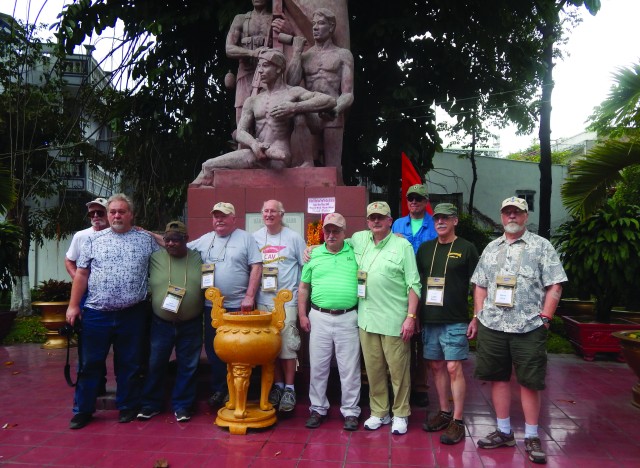

Thirty years later, Garrod and other veterans traveled back to the site on the anniversary of the offensive as a way to find closure for what they saw that day.

They also visited a statue in a nearby park that honors those who were lost or suffered as a result of the battle.

Because of the devastation the war had caused, Garrod expected to see animosity on the faces of the Vietnamese people.

"Instead we found gracious, friendly people," he said. "Even the veterans from the north whom we met … greeted us with hugs. It was very surprising. They had definitely moved on."

Social Sharing