FORT SILL, Okla. (Jan. 24, 2019) -- The man behind "Flipper's Ditch" is the stuff of legend around Fort Sill.

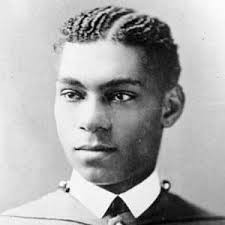

Lt. Henry Ossian Flipper entered the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, N.Y., in 1873 and became its first African American graduate four years later. As the first black commissioned officer in the regular Army, he was assigned to Fort Sill as one of the "Buffalo Soldiers" in the 10th U.S. Cavalry, one of only two all-black cavalry units in the Army.

While stationed here from July 1877 to February 1879, Flipper designed a ditch to drain pools of water that served as breeding-grounds for mosquitoes. Thus ended a malaria outbreak that had killed many Fort Sill Soldiers. Portions of Flipper's ditch, lined with native limestone, can still be seen today on the Fort Sill Golf Course.

His other accomplishments included surveying and supervising construction of a road from Fort Sill to Gainesville, Texas, and building an intricate telegraph line from Fort Supply, Indian Territory, to Fort Elliott, Texas. He also served as part of the military escort that removed Quanah Parker and his band of Comanches to the reservation at Fort Sill.

His military career took a sad turn while he was assigned to Fort Davis, Texas, in 1880. There, Flipper was court-martialed and received a dishonorable discharge from the Army under circumstances that historians of today deem unjust. In 1976, the Department of the Army granted Flipper an honorable discharge, and on Feb. 19, 1999, President Clinton officially pardoned him.

Flipper lived to the age of 84 and carved out a distinguished career as a surveyor, mining engineer, land claims expert, writer, and oilman despite the stain on his record. Today his name is hallowed wherever people gather to remember the "Buffalo Soldier" heritage.

What made him what he was? As luck would have it, we have the answer to that question in Flipper's own words.

He became a published author in his first year at Fort Sill. In 1878 the New York firm of Homer Lee & Co. published a memoir by him covering his four years as "The Colored Cadet at West Point."

A digitized copy can be found online at https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/flipper/flipper.html , and Flipper penned the book's preface at "Fort Sill, Indian Territory, 1878."

Flipper was born into slavery on March 21, 1856, in Thomasville, Ga. Both he and his mother, Isabella, were "the property" (sic) of the Rev. Reuben H. Lucky, a Methodist minister. His father, Festus Flipper, was by trade a shoemaker and carriage-trimmer, he was owned by Ephraim G. Ponder, a slave-dealer. When Ponder moved to Atlanta to establish a number of "manufactories," Henry Flipper's parents faced the prospect of a forced separation. They pleaded with both owners to keep them together. Neither was willing to buy the other's slaves, but Lucky did consent to part with Flipper and his mother if a buyer could be found. Festus Flipper finally entered into an agreement to pay for his own wife and child out of his own pocket, with Ponder to return the sum to him whenever convenient.

As described in the book, conditions in the Ponder household were such that the slaves managed to live a fairly unencumbered existence. Disaffection between Mr. and Mrs. Ponder led to their separation, and under their marital contract neither could sell what they jointly owned without permission from the other. Mrs. Ponder might threaten to sell them and send them to the Red River, but the slaves knew these were but empty threats.

The Ponders' slaves were, with the exception of the ordinary household servants, trained mechanics who were permitted to handle their own business dealings. They could hire out their services and get paid for it. They could thus accumulate wealth. In addition, one mechanic obtained Mrs. Ponder's permission to use their woodshop at night as a place to teach their children the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

During the final stretch of the Civil War, Mrs. Ponder fled with all the slaves to West Macon, Ga., to escape the wrath of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's "March Through Georgia." After the burning of Atlanta, the Flipper family returned there to assist in the rebuilding. By then, they had become prosperous enough to pay the wife of an ex-Rebel captain to tutor their two sons, Henry and Joseph. As better schools became available, thanks to the American Missionary Association, the boys transferred to these.

By 1869 the association had opened Atlanta University, and Henry Flipper was a member of its freshman class at the collegiate level. In the spring of 1873, Georgia's Fifth District Congressman, J.C. Freeman, nominated Flipper for West Point, after Flipper assured him he would not let the congressman down. Many whites tried to discourage him from making the attempt. Some of them falsely led him to believe that a black cadet from South Carolina, James Webster Smith, had just been dismissed.

At the 11 a.m. mail call on his second day on campus, Flipper reports being surprised to receive a letter from Smith himself. The letter had gone missing by the time Flipper began preparing his book for publication, but he could still remember Smith's cryptic words of advice: Do not fear blows or insults, but avoid forward conduct if you wish to avoid certain consequences, "which, I have learned from sad experience," would be otherwise inevitable. Richard Reid, in an article published by The Times and Democrat of Orangeburg on June 10, 2012, provides a litany of the "consequences" that Smith and his first black roommate, Michael Howard of Mississippi, were forced to endure.

After reading the letter, Flipper asked to meet Smith, and was escorted to Smith's room at 4 p.m. that same day. The meeting was necessarily brief, as Smith was getting ready for drill, but Flipper writes that Smith did give him some valuable advice. The two became bunkmates for the rest of that year.

Flipper was anything but forward in his conduct while at West Point, yet it didn't seem to make any difference. He reports that for the first few days there were white cadets who ventured to speak to him in a friendly way. True, he was subjected to dressing-downs from superior officers for not adhering to correct procedure, but they did this to all the "plebes," and other first-year students drew much worse criticism than did Flipper.

Nevertheless, his white classmates quickly closed ranks against him. Flipper was led to suppose that those who had spoken with him were warned not to do so any more, or they would themselves be ostracized.

Sadly, Smith failed his examination in Natural and Experimental Philosophy and was dismissed at the end of Flipper's first year. Smith was the fourth African American to wash out at West Point, the others being Napier of Tennessee, Howard of Mississippi, and Gibbs of Florida.

Smith returned to his home state, where he became commandant of cadets and professor of mathematics and military tactics at the State Agricultural College & Mechanics Institute at Orangeburg (now South Carolina State University). He served in this capacity until his death from tuberculosis on Nov. 30, 1876.

Immediately after Smith's dismissal, a rumor went around West Point that Flipper intended to resign.

"I learned of the rumor from various sources, only one of which I need mention," Flipper writes. "I was on guard that day, and while off duty an officer high in rank came to me and invited me to visit him at his quarters next day. I did so, of course. His first words, after greeting, etc., were to question the truth of the rumor, and before hearing my reply, to beg me to relinquish any such intention. He was kind enough to give me much excellent advice, which I have followed most religiously. He assured me that prejudice, if it did exist among my instructors, would not prevent them from treating me justly and impartially. I am proud to testify now to the truth of his assurance. He further assured me that the officers of the Academy and of the Army, and especially the older ones, desired to have me graduate, and that they would do all within the legitimate exercise of their authority to promote that end. This assurance has been made me by officers of nearly every grade in the Army, from the general down, and has ever been carried out by them whenever a fit occasion presented itself."

In spite of all those who predicted he would be "slaughtered" during his senior year, Flipper beat the odds to become West Point's first African American graduate. He ranked 50th in a class of 76 in 1877.

Social Sharing