FORT SILL, Okla., Dec. 20, 2018 -- As the first official photographer of the newly-created Fort Sill frontier Army post, William Stinson Soule was uniquely situated to capture a moment in time.

His job required him to do two things: record progress on the buildings going up around the Old Post Quadrangle, and take pictures of the officers and their families.

But what he is best-known for today is something he took it upon himself to do on the side. He captured images of all the Plains Indians who would let him, even as their old way of living was dying out.

Because he took a particular interest in their doings, it is possible to see exactly what people such as Satanta (Set-tain-te), Big Tree, Satank, Stumbling Bear, and Kicking Bird actually looked like.

When archivists mounted a collection of Soule's work for a 2009 show in Beverly Hills, Calif., they had this to say: "His photos of Indians in the area -- Kiowas, Apaches, Cheyenne, Wichitas, Caddos, Arapahoes, and Comanches -- (are) the first known single collection of Indian photographs and one of a very few to record Indians not yet living on reservations. They precede Edward Curtis' photos by 30 years.

"Soule photos were taken at a time when Indian tribes were in a fierce struggle against whites and many had been relocated to Oklahoma. The Sand Creek and Washita Massacres of the plains tribes were recent and some of his subjects were prisoners captured by Gen. George Armstrong Custer. Yet the Indians, who called photographers 'shadow-catchers,' appear to be willing subjects. It was not long after these photos were taken that the Indian life he captured vanished."

CARBINE & LANCE

Most of the iconic photographs of American Indians that grace the pages of "Carbine & Lance: The Story of Old Fort Sill" exist because of him. Soule did not receive proper credit for his photographs when that definitive book was first published in 1937, nor in subsequent editions that appeared in 1942 and 1969.

However, the author, retired Col. Wilbur Sturtevant Nye, decided to correct this oversight when he wrote the prequel to "Carbine & Lance" published by University of Oklahoma Press in 1968.

The second half of "Plains Indian Raiders: The Final Phases of Warfare from the Arkansas to the Red River" consists almost entirely of Soule's photographs and information about them.

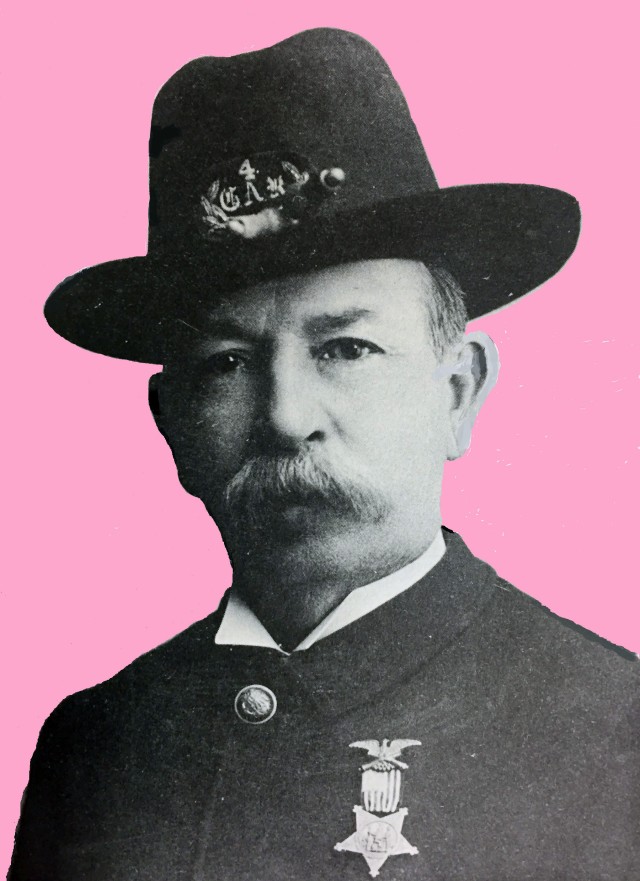

Little is known about Soule's early life, other than that he was born at Turner, Maine, on Aug. 28, 1836, and grew up on a New England farm.

Nye says he must have had good schooling because the photographer of those days had to be versed in chemistry, optics, and art, and Soule gave his occupation as "photographer" when he enlisted in the Army in 1861.

He may possibly have been associated with his older brother John in a photography studio in the Boston suburb of Melrose, Mass., prior to the outbreak of the Civil War.

ENLISTMENT

Soule enlisted in Company A, 13th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. This unit served in major campaigns in Virginia during the first year of the war, but its most severe test came at the Battle of Antietam. Soule's regiment alone lost 600 men, nearly its entire strength, in less than 20 minutes.

Soule was struck in the hip by a Minié ball and evacuated to a field hospital at Keedysville. From there he was moved via the old Cumberland Valley Railroad to a base hospital at Harrisburg, Pa.

His recovery was slow and incomplete. When his regiment was mustered out in September 1864, by expiration of term of service, Soule re-enlisted in the Invalid Corps, which consisted of men incapacitated for field service, but used for administrative work.

In 1865 Soule set up a photographic studio in Chambersburg, Pa. No one except professionals owned cameras in those days, yet there was a great demand from Soldiers and veterans for small portraits, called cartes de visite, to be given to their relatives or sweethearts. Soule had a thriving business in such photographs.

In 1866 or early 1867 an accidental fire damaged his studio.

Although Soule's wound still bothered him and his muscles remained weak from his long hospital stay, he decided to follow the advice of newspaper editor Horace Greeley and "go west."

HEADING WEST

He sold his photographic business and used the proceeds to buy a new camera and darkroom supplies.

He then took the "steam cars" to St. Louis and made his way from there to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., where his former commander at the Invalid Corps was now head of the Department of the Missouri, which at that time had nominal oversight of Army operations for this region of the country.

Soule heard of a job vacancy at Fort Dodge, Kan., a new post on the Arkansas River route (the old Santa Fe Trail).

John Tappan needed a chief clerk for his sutler's store there. (A sutler was a civilian who followed the Army and sold provisions to the Soldiers.) Soule applied for the job and got it.

He went by rail to Salina, Kan., and the next day hopped a stagecoach bound for Fort Dodge. Soule used his off-duty time at Fort Dodge to resume his photographic work.

He also took up horseback riding, and that, coupled with the more congenial climate, quickly restored his health.

In late 1868 or early 1869 Tappan and Soule went as traders to Camp Supply, Oklahoma Territory. Tappan had lost his franchise at Fort Dodge, and he never secured a formal permit to trade at Camp Supply, although he remained there several months.

ARRIVAL HERE

It is not clear when Soule first went to Fort Sill. He may have accompanied Col. Benjamin Grierson on his reconnaissance in December 1868, as there are several Soule photos of Grierson and his staff at Medicine Bluff.

It is certain that in 1869 Soule obtained a job with the Engineer Corps as Fort Sill's first official post photographer.

He was hired to take pictures of the successive steps in the construction of the post.

When Neal and John Evans built the first post trader's store where McBride and Cureton avenues meet up today, Soule obtained a concession for a photographic studio in their main building. He maintained this studio for six years.

According to Nye, Grierson, the first commander of Fort Sill, invited Soule to dinner on Christmas Day 1874, and wrote to his wife, Alice, that he tried to dissuade Soule from his intention of returning to the East.

However, Soule did go to Washington, D.C., with a delegation of Indians on a visit to meet the president. While there, Soule met and fell in love with Ella Augusta Blackman.

They made plans for an early marriage, and Soule hurried back to Fort Sill to wind up his affairs and bring his photographic equipment and other assets back to Washington.

"To his dismay he found that a business associate, or partner, whose name is not known to me, had gone to California with everything except, perhaps, one of the albums and the negatives of the Indian collection," Nye wrote.

Sixty-nine negatives eventually turned up in the Los Angeles County Museum, some 80 or 90 years later.

Soule, however, had to begin married life on a shoestring, taking a job in Philadelphia and later moving to Vermont before he was able to restart his career in photography.

After retiring, Soule lived out his days in Brookline, Mass., active in veterans' and philanthropic works.

He did that by going into business with his brother as The Soule Art Company in Boston.

Eventually he bought out his brother and continued to operate the firm until his retirement in either 1900 or 1902, depending on the source.

From then until his death in 1908, Soule lived with his family in Brookline, Mass. He was active in veterans' and philanthropic work in his later years.

Social Sharing