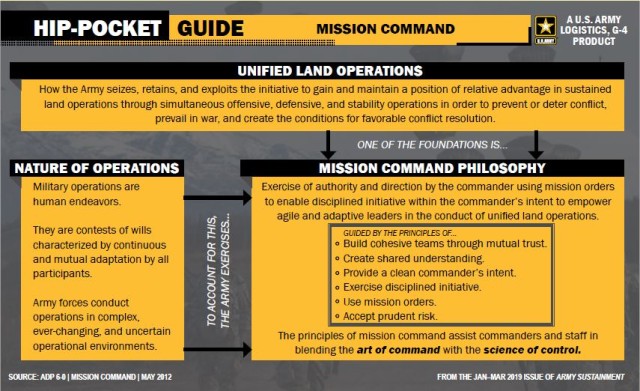

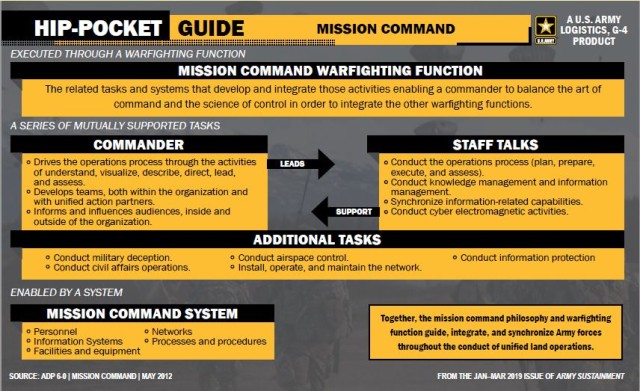

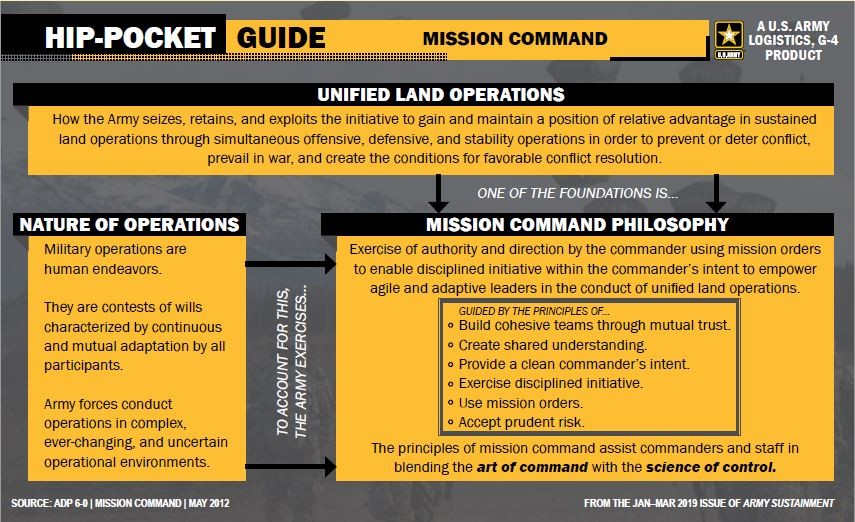

To continue to drive improvements in logistics readiness, commanders need the freedom to exercise greater authority based on mutual understanding and shared trust. This is the philosophy of mission command.

I see mission command growing in importance because it encompasses so much of how the Army is trying to reform--establishing smaller headquarters, pushing decisions and authorities down the chain, reducing bureaucratic Army-level requirements, and modernizing with emerging technologies. We are not trying to run every decision through the Pentagon; we want decisions to be made in the field.

With mission command, once commanders know the direction Army leaders want to take, they have room to act on their own. It is no longer an "I say you shall carry this out" kind of atmosphere. It is a much more inclusive "I'll give you guidance, and we'll accomplish success together" atmosphere. With this culture, once commanders at every echelon know intent, they can put forth initiatives to capitalize on opportunities or react to changes in the environment.

MISSION COMMAND IN PRACTICE

I know firsthand how well mission command can work because for the past two years I have used it every time I have written this column and talked to commanders in the field.

I have been a Johnny-one-note, discussing one topic: how to improve our basic skills in dealing with supplies and maintenance. We were so used to forward operating bases with primarily contracted support in Afghanistan and Iraq that we lost the skills to move and maintain our own equipment. I wanted to put readiness, especially our ability to set a theater, back at the forefront because in future fights we will go as we are.

My communication with commanders was intended to develop a shared understanding and shared trust up and down the chain of command. I wanted them to have a clear vision of the end state we needed, and the Army gave them the resources to make changes.

Today we are doing more home-station training on basic skills. We have increased rotations at the National Training Center, including with our Army Reserve and National Guard units, so that every Soldier can build muscle memory to execute expeditionary sustainment.

Now when I visit units, I see commanders embracing our call to action. Gains that we have made are a testament to their leadership in not only relearning old skills but also adapting today's technologies to improve fundamentals that make us more effective. These leaders have changed our culture.

A while back, I visited a unit where Soldiers were holding command maintenance events in the motor pool, but the top commanders did not attend. If the top commanders were not in the motor pool, was it really a priority? I do not think so. Where the commanders are, and where they put their attention, is where the emphasis will be.

A MISSION COMMAND CULTURE

I will keep using mission command to stress issues that are important. Moreover, as logisticians, we should be asking how we build a better culture of mission command and what we can do to improve command and support relationships. Here are my recommendations.

Understand the strategic environment. I encourage every commander to be familiar with the National Defense Strategy, which lays out the threats and what we need to do to prepare for multi-domain operations.

The strategic environment is changing rapidly. Russia is restructuring its military to be more competitive. China is developing expeditionary military forces. We still must be prepared to fight tonight in Korea, be ever watchful of Iran, and engage violent extremist organizations across Africa, the Middle East, and Afghanistan.

From a logistics perspective, one of the things that we can no longer do in this strategic environment is depend on mountains of steel. Our supply chain must be agile so that when facts change on a battlefield, courses of action can change too.

We have set a goal for brigade combat teams to sustain themselves for seven days without resupply. Goals involving demand reduction are always good. I remember as a lieutenant we talked about energy reduction, and over the years we have done some things to accomplish that. However, a once-a-week resupply will only happen if we have well-informed commanders who know the strategic environment and encourage organizational agility through not just words but also actions.

BUILD TRUST. The first principle of mission command is to create cohesive teams through mutual trust. Trust up and down the chain of command is what makes or breaks mission command. Soldiers know their capabilities and responsibilities. And trust enables appropriate actions without the need for supervision. As you gain trust, junior members of the team take on added responsibility, which builds a bench and helps us to manage and keep good talent.

In building trust, allow Soldiers to make mistakes, so long as they are not unethical, illegal, immoral, or unsafe. From mistakes, Soldiers learn what right looks like. Commanders do not need to hammer Soldiers all the time. Give them responsibilities, let them try to take care of things, and then make sure you know how it all worked out.

FOCUS ON WHAT IS IMPORTANT. Mission command requires focus. You cannot have half of your force going one way and the other half going a different direction and expect to be successful.

The biggest enemy of mission command is a leader who wants to know everything. Information is important, but to what end? It is better to focus on a few items. In an era where information is everywhere, that is not always easy.

YOU DON'T HAVE TO OWN IT TO INFLUENCE IT, BUT YOU MUST BUILD RELATIONSHIPS. Every time I talk about going back to the basics, I try to provide clear intent so I can influence what I see as a need, but I do not own the command authority to achieve it.

Commanders do not need to be in the chain of command to influence sustainment decisions. However, they need to build relationships and partnerships if they are going to be players.

When I was commander of the 21st Theater Sustainment Command in Germany, we did not have Army Reserve or National Guard units train with us. Now they do train with the unit because the strategic environment has changed and the needs have changed. If we are going to be successful in a fight that requires us to rapidly move into a theater, these new relationships that have been built will be key.

Also, you do not need to be in the direct chain of command to help young leaders succeed. It is our responsibility to coach, teach, and train young Soldiers to make sure they are successful.

Following wars, there is a tendency for bureaucracies to grow. This slows decision-making, kills initiatives, and erodes trust. Army leaders want to ensure that does not happen this time. We are not re-fighting yesterday's war; we are modernizing and preparing for our next mission. To win that mission, we need commanders who understand leadership's intent and are empowered to be agile and adaptive in unified land operations.

--------------------

Lt. Gen. Aundre F. Piggee is the Army Deputy Chief of Staff, G-4. He oversees policies and procedures used by all Army logisticians throughout the world.

--------------------

This article was published in the January-March 2019 issue of Army Sustainment.

Related Documents:

Hip-Pocket Guide Jan-March 2019 [PDF]

Social Sharing