Ask logisticians if movement control works, and many will say it does not. Ask how it works, and you'll get many different answers.

The Army's support of contingency operations from forward operating bases using contracted assets has altered how we think about movement control. As the Army shifts toward large-scale combat operations (LSCO), it must ensure the force is optimally designed and structured to manage distribution networks to be ready for war. The risk associated with "figuring it out" on the battlefield against peer threats will be high. The Army must optimize this critical capability now.

ORGANIZE DURING PEACE

The Army is manned, trained, and equipped to fight and win our nation's wars. It creates its units with that mentality and designs movement control to support the fight during major combat operations. It helps execute key operations like deployment, reception, staging, onward movement, and integration, replenishment, resupply, redeployment, and other movements.

How the Army organizes in peacetime is of secondary importance, yet it can play a pivotal role in warfighting. Why doesn't the Army organize at home station the way it will fight in LSCO?

This article advocates for a new vision of movement control implemented with the following low-cost organizational solutions designed to enhance readiness and improve effectiveness in support of warfighters:

• Redesign movement control teams (MCTs) to grow leaders and enable movement control organizational changes.

• Reorganize movement control battalions (MCBs) and MCTs to improve warfighter support during LSCO.

REDESIGN MCTs

The first step in improving movement control is to redesign MCTs. This will allow the Army to fix the military occupational specialty (MOS) 88N (transportation management coordinator) grade distribution, grow better leaders, enhance the mobility warrant officer community, and most importantly, enable a task organization change for movement control forces.

MCTs are small detachments of 21 personnel designed to expedite, coordinate, and supervise the various transportation nodes and modes in an assigned area. They are designed to operate as four teams that can execute various mission sets: intermodal, area, movement regulation, documentation, and division support. To put it simply, they help manage the distribution network for whomever they support.

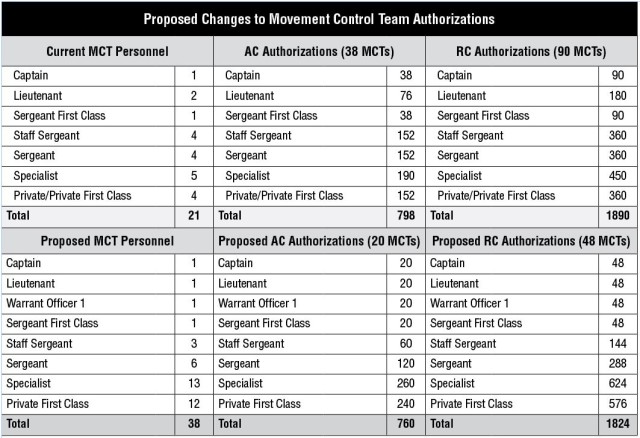

The current MCT design has resulted in some personnel structure challenges. The Army strives to have a ratio of roughly 51 Soldiers to 49 noncommissioned officers (NCOs). In the grade cap distribution matrix in figure 1, the line indicates how many 88Ns are authorized at each grade, and the bars depict the number of authorizations the Army currently has at each grade.

There are a couple negative consequences to the lack of balance in the Army's 88N structure. First, the 88N field lacks a "bench" from which to promote Soldiers. Specialists can make sergeant with little effort because the 88N field structurally needs more sergeants than specialists. Additionally, 88N specialists get little time as leaders because they have one or zero subordinates. This results in junior Soldiers with little experience in their technical field or in leading troops before promotion.

Second, the Army does not require individual MOSs to be balanced, but it does require balancing in the overall 88-series career field. The NCO overages in the 88N population means other 88-series MOSs must have fewer NCOs than they should, resulting in tougher promotion numbers. For example, the average pin-on time to sergeant first class for an MOS 88M (motor transport operator) or MOS 88H (cargo specialist) is 14.3 and 15.4 years respectively; for 88Ns, it is 13.1 years.

In order to grow better leaders, NCOs in the MCTs need time to lead Soldiers and hone their craft. One way is to change the proportion of NCOs to Soldiers. The typical squad leader is a staff sergeant with two team leaders who each have a few Soldiers. This enables NCOs to receive missions, delegate tasks to subordinates, then lead and follow up to ensure completion. Developing leadership qualities requires dealing with both positive and negative behavior from Soldiers and taking time to teach, coach, and mentor.

BALANCE THE FIELD

In today's Army, there are many competing priorities. Achieving the growth of Soldiers in a unit is incredibly difficult. It requires force designers to work within their existing personnel structure for redesigns.

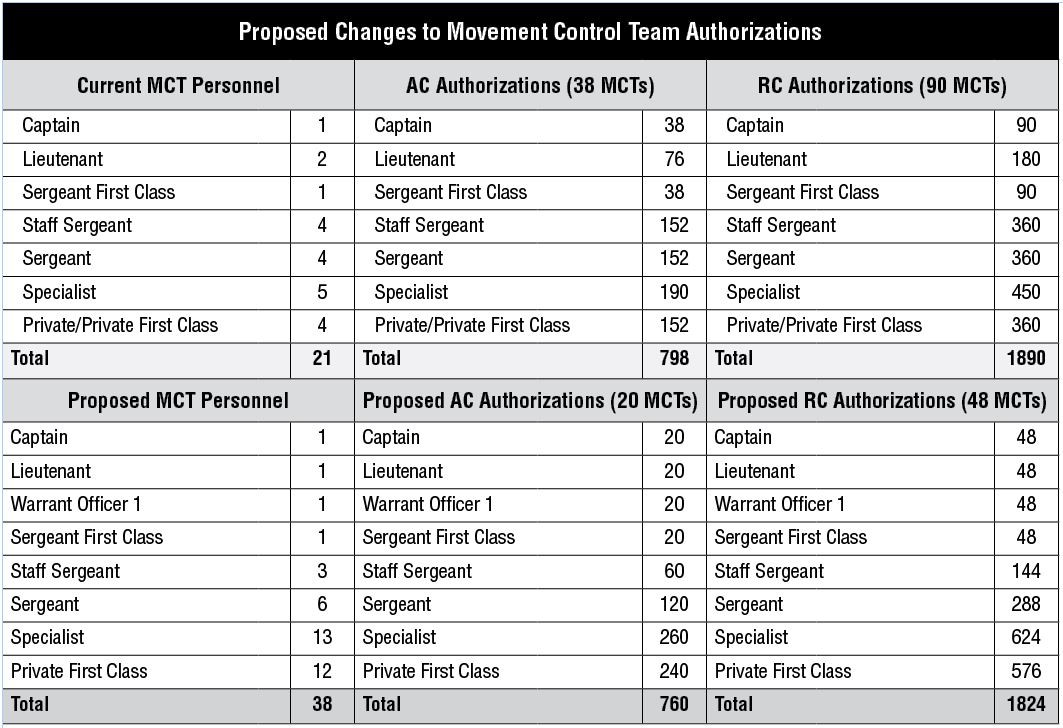

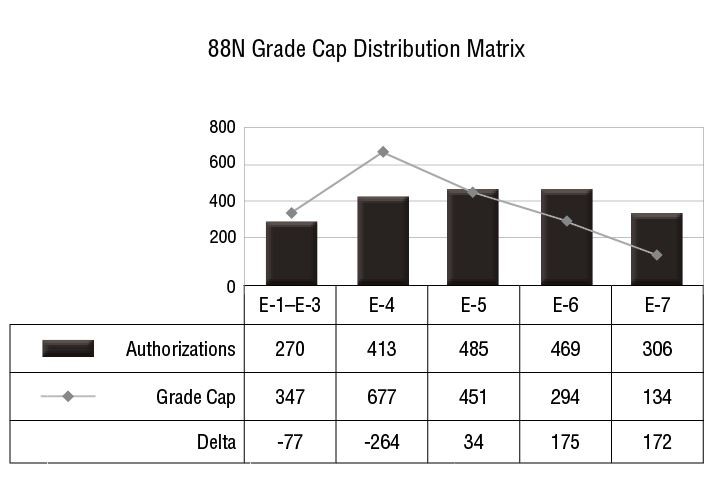

One way to achieve the aforementioned desired effects and improve movement control is proposed in figure 2 on page 52. This design would reduce the number of MCTs from 38 to 20 in the active component and from 90 to 48 in the reserve component. It also allows excess spaces to be re-allocated to growing the MCB's staff, giving it vital capability for managing movements in LSCO.

The proposed design puts the sergeant first class in charge of an element that is roughly the same size as the elements their peers in other companies lead. It allows a staff sergeant to lead a squad of 10 Soldiers. It grows junior Soldiers and reduces the number of NCOs, which helps to fix some of the grade distribution issues in the 88N structure. It also leaves some leftover authorizations that can be used to supplement the MCB staff.

This design also introduces mobility warrant officers into the MCTs. It provides a great opportunity for young warrant officers to get their feet wet and have a chief warrant officer 3 or 4 mentor them prior to becoming a brigade mobility officer.

But more importantly, as officers focus on learning all the disciplines of the sustainment warfighting function, the Army's functional expertise will be more frequently provided by the warrant community. Institutional instruction is limited, requiring most new mobility warrant officers to learn through the self-development and experience domains. A logical entry learning point to gain distribution experience is an MCT.

Ask every MCT or MCB commander what person they need most for their units and the unanimous response is a supply specialist. MCTs will undoubtedly support movements across the corps and theater areas of operation, and managing equipment that is spread across multiple locations will become a more challenging endeavor. Now is the opportunity to provide a dedicated supply representative to their formations.

The original MCT was designed to split into four sections to operate at different nodes. The redesign would not change the fundamental operating concept; however, a staff sergeant would lead a 10-person squad with two four-person sections each led by a sergeant.

This increases the total number of teams capable of operating at nodes from four to six per MCT. A sergeant could be in charge of a smaller node (trailer transfer point, main supply route checkpoint, etc.), while a more senior person could operate the larger nodes (airport, seaport, etc.) The team can be broken down further depending on the area of operations and mission set. As the number of MCTs decreases, the area they cover must increase correspondingly. The new unit will be plenty capable to execute the expanded requirements.

REORGANIZE MCBs AND MCTs

The redesign of MCTs gives the Army freedom of action to implement a new task organization for movement control. It allows the Army to prepare for LSCO by posturing forces in peace like they will fight in war. This will increase MCTs' deployment readiness by giving them realistic and focused training repetitions.

The Training and Doctrine Command's draft version of an echelons-above-brigade (EAB) concept states that the Army must prepare to operate dispersed. It says, "To achieve depth, simultaneity of action, and ensure accomplishment of campaign objectives when operating dispersed, EAB headquarters must coordinate shaping and sustaining efforts, conduct intelligence synchronization, optimize task organization and command and control relationships."

The concept also discusses that EAB units must manage terrain and direct movements. "Past efforts to fight dispersed over wide areas (the Pentomic Army of the late '50s and the Cold War Army in Europe) disclosed considerable problems of coordination and manning. Specifically, the Cold War Army found that terrain management, movement control … all required intense command and staff attention."

The Army must reorganize its logistics constructs designed to operate in counterinsurgency environments into the critical enabling capabilities warfighters need to fight and win on future battlefields against peer competitors.

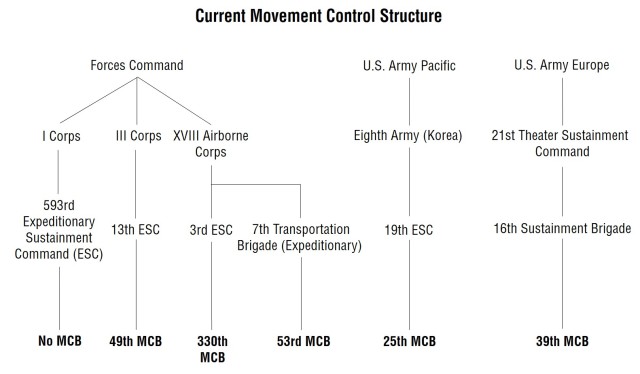

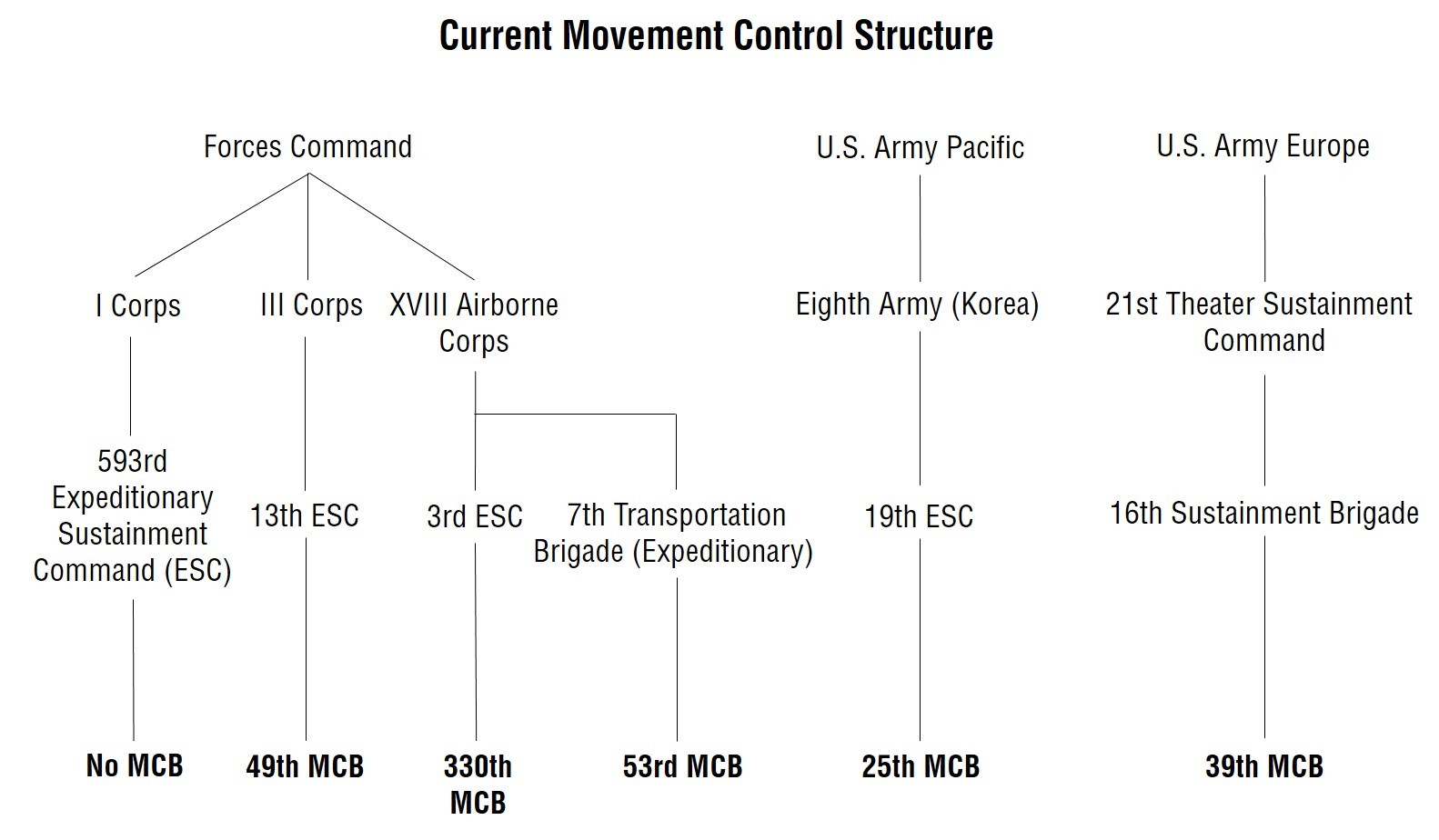

To prepare for war, the Army must realign its movement control structure. (See figure 3 on page 53.) Numerous I Corps after action reviews indicate that the struggle to manage movements during exercises and deployments could be remedied by moving one of the two MCBs currently under the XVIII Airborne Corps. The 53rd MCB could be moved under a command implementation plan and relocated to Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM), Washington. This action is already underway at the Forces Command and should be approved as soon as possible to provide crucial support to the I Corps mission.

This would also have a secondary effect of the 53d MCB supporting the only major power projection platform on the West Coast when not deployed or on deployment cycle. Both Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Fort Hood, Texas, each have MCBs providing support when available to the eastern and central power projection platforms, while JBLM continues to go without.

JBLM is the most likely installation to deploy large-scale forces on short notice to counter threats in the Indo-Pacific Command area of responsibility. It is also one of seven primary mobilization force generation installations, which serve as reserve component mobilization sites. I Corps will continue to be hindered in coordinating the preplanned or rapid deployment of forces to support geographic combatant commander needs until it is resourced an MCB.

To make this new task organization of MCBs combat effective, the Army must relook how it assigns MCTs. There is no discernible logic to the Army's current emplacement of MCTs and how they will help manage our transportation networks if we were to mobilize for war.

Forward-stationed MCTs are asked to manage large areas while many continental U.S. MCTs remain underutilized. Some installations have four MCTs, some have two, and others have one. The XVIII Airborne Corps has 15 MCTs in its organizational hierarchy, but I Corps has one. How can we best standardize and align units to optimally train and support the Army?

The Army must align these newly designed MCTs to units where their support can be best employed: divisions and forward-deployed geographic combatant commands that support contingency operations, exercises, and extended or heavily used lines of communication. These areas are considered the most likely to host conflict.

ATTACH MCTs TO MCBs

To truly train as we fight, MCTs should no longer be attached to special troops battalions or combat sustainment support battalions under sustainment brigades. They must be attached to MCBs.

The dispersion of Soldiers across many states adds challenges, but sustainment forces already operate this way across numerous commands. It can and should be done. Additionally, MCBs should not be assigned to sustainment brigades but rather to ESCs or TSCs. This is how it will look in war, and this is how it should look in peace.

MCBs know best how to employ MCTs. They speak the technical language, know the mission, and know the challenges associated with managing MCTs. They provide the best opportunity for MCTs to get great training. As a direct plug into the ESC, the MCB understands the major movements and missions in its area of responsibility and can employ its MCTs to assist. The MCTs gain valuable experience by performing real-world support missions.

Movement control is inherently dispersed and promotes decentralized execution much like the EAB concept dictates. Let MCBs manage MCTs in different states to become proficient in what will certainly be a real-world scenario.

With this alignment, MCTs would habitually support their designated divisions or Army service component command MCB, and MCBs would support their designated corps or higher command. It would enable a clear and consistent movement control hierarchy that is customer friendly.

What we must prevent is MCBs getting turned into generic sustainment battalions. This distracts from their core mission of providing in-transit visibility, coordinating transportation assets, and providing command and control of MCTs. The MCB staff simply is not built to support a large number of troops.

It is too easy to think of an MCB as another combat sustainment support battalion and use it as such. This changes its mission from controlling movement to executing sustainment missions. At best, this splits the MCB's focus so that it does neither mission as well as it could.

Field Manual 3-0, Operations, describes a clear shift back to LSCO in the Army's warfighting strategy. The Army's distribution network is vast and complicated, and experts in its use will be a valuable commodity on the future battlefield. Movement control will be key in supporting LSCO, and the time is now to optimize the Army's organizational structure to better execute it.

Movement control requirements have been captured and are repeatedly emphasized in the new Field Manual 3-0. The requirements are heaviest within the support areas and their command posts. Now, more than ever, it is critical to get movement control right. The Army must redesign and reorganize to best execute movement control.

Movement control is critical in both peace and war. It is long overdue for a comprehensive reorganization. The Army does not design units and task organization to improve garrison operations, but it does make changes to improve warfighting capability for LSCO.

This proposal provides the opportunity to do both. It will strengthen training, relationships with supported units, and the Army's ability to execute the core tasks of movement control in the next fight.

--------------------

Capt. Alex Brubaker is the proponency officer for the Transportation Corps. He received his commission from the University of Michigan and is a graduate of the Transportation Basic Officer Leader Course, Combined Logistics Captains Career Course, Support Operations Course, and Theater Sustainment Planners Course.

--------------------

This article was published in the January-March 2019 issue of Army Sustainment.

Social Sharing