The following is an article from the U.S. Army Special Operations Command Historian Office.

FORT BRAGG, N.C. -- November 28, 2018 marks the 75th anniversary of the establishment of one of the most daring U.S. Army Special Operations units of World War II: the Alamo Scouts.

U.S. Army LTG Walter Krueger, commander of the U.S. Sixth Army (also known as the 'Alamo Force'), established the Alamo Scouts in the Southwest Pacific Area in late 1943. With an area of responsibility composed more of water than land, Krueger realized he needed a small unit of skilled men with specialized reconnaissance expertise to provide him with information needed to defeat the Japanese. As a result, on November 28, 1943, he directed that select soldiers be trained in the special skills of amphibious reconnaissance, jungle warfare, and clandestine operations behind enemy lines.(1) They would become known as the Alamo Scouts.(2)

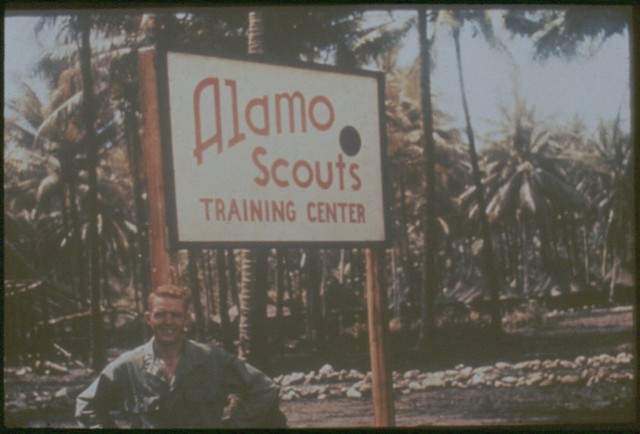

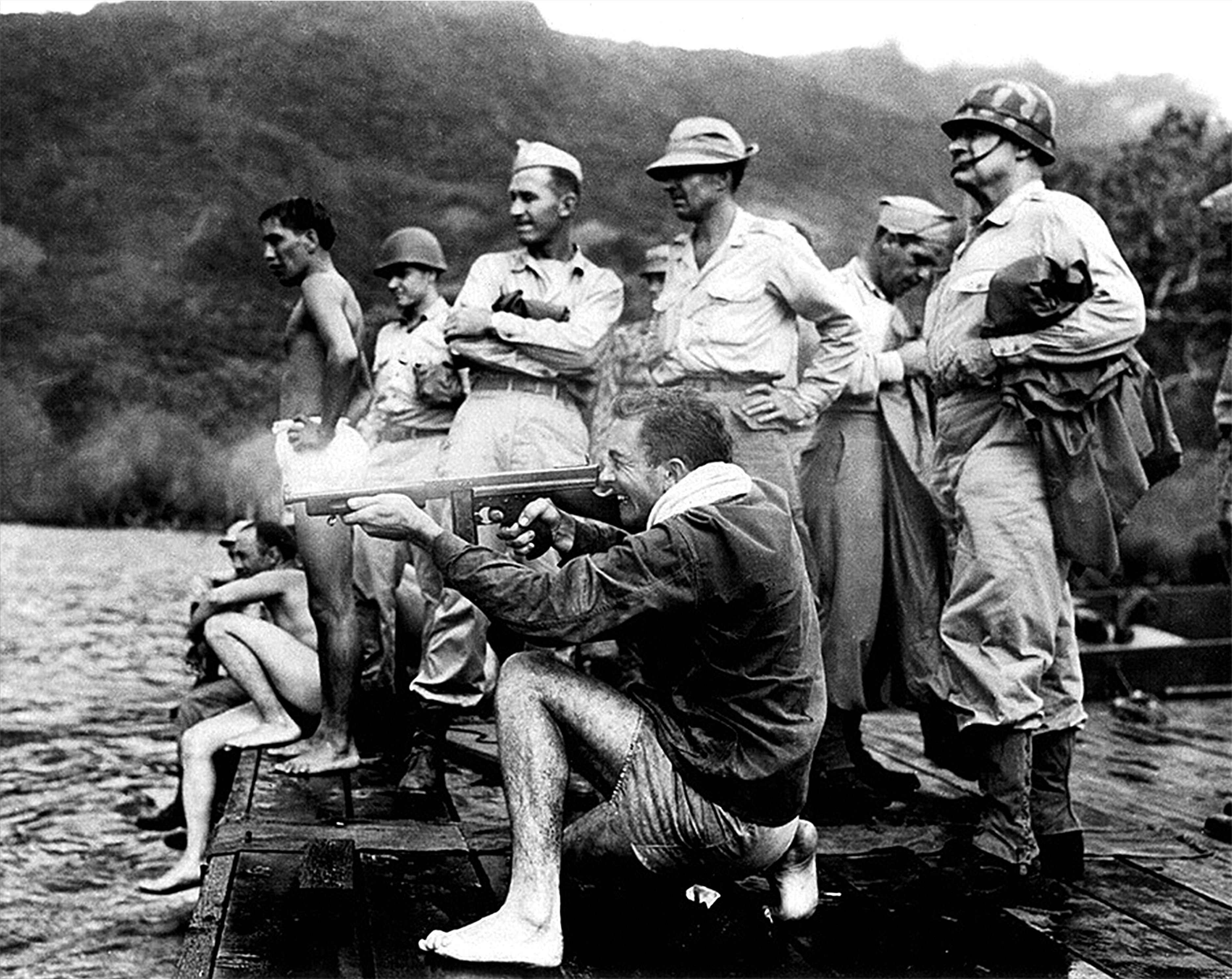

An Alamo Scouts Training Center was established and an innovative assessment and selection process was developed. An evolving program of instruction incorporated both internal and external evaluations throughout the course to ensure only the best soldiers were selected for Alamo Scouts training. Combat veteran volunteers for the course were given intensive training in weapons, communications, intelligence reporting, physical conditioning, amphibious reconnaissance skills, and extended patrolling techniques. Students also learned to infiltrate enemy territory employing a variety of means, ranging from swimming and operating rubber boats to Patrol Torpedo Boats, submarines, and Catalina flying boats. Students trained for six weeks, unaware of their status until they graduated. Of the several hundred students who attended the course, only 138 were selected as Alamo Scouts.

After graduating, Alamo Scouts were organized into ten teams of five-to-ten men and assigned to tasks ranging from special reconnaissance to direct action and prisoner/hostage rescue. Their patrol reports contained valuable information that higher units used in the field, as part of the larger military campaign. By war's end, the Scouts conducted more than 100 missions behind enemy lines, a remarkable feat.(3) The Alamo Scouts were to provide amphibious reconnaissance on Kyushu Island for the invasion of mainland Japan when the dropping of two atomic bombs forced Japanese surrender. After a short time as security for key officers during the occupation of Japan, the unit was disbanded in Kyoto in November 1945.(4)

Several members of the Alamo Scouts found their way into the ranks of Army Special Forces later in their careers. Aspects of Alamo Scout training, including their use of peer evaluations during training, were incorporated into the Special Forces Qualification Course and continue impacting Army Special Operations Forces to this day.(5) Moreover, the Alamo Scouts clearly demonstrated they are "value-added" and how Special Operations Forces can provide unique skills to conventional forces in major theaters of operation.

-----

Author:

The Deputy U.S. Army Special Operations Command Historian, Dr. Michael E. Krivdo, earned his PhD in Military and Diplomatic History from Texas A&M University. He is a former Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance Officer with varied special operations research interests.

-----

Note: This modified article originally appeared in Veritas: Journal of Special Operations History 14:2 (2018): 48. Veritas is a publication of the United States Army Special Operations Command History Office, Fort Bragg, NC.

_______________________

(1) Larry Alexander, Shadows in the Jungle: The Alamo Scouts Behind Japanese Lines in World War II (New York, NY: NAL Caliber, 2009), 44.

(2) Lance Q. Zedric, Silent Warriors of World War II: The Alamo Scouts Behind Japanese Lines (Ventura, CA: Pathfinder Publishing, 1995), 40-41, 43-46; Alexander, Shadows in the Jungle, 51-66.

(3) Alexander, Shadows in the Jungle, 5.

(4) Zedric, Silent Warriors of World War II, 241-49.

(5) Kenneth Finlayson, "Alamo Scouts Diary," Veritas: Journal of Army Special Operations History 4:3 (2008): 17; Michael E. Krivdo, Text of Class on "History of Army Special Forces," Document, Class outline for Special Forces Qualification Course, 30 November 2016, copy in the USASOC History Office History Support Center, Fort Bragg, NC.

Social Sharing