FORT RILEY, Kan. -- On today's battlefield, Soldiers can be tens to hundreds of miles from a medical treatment facility. If injured, they rely on the ability of their medics to get them safely to higher-level care.

"The best way that it's been described as is: the self-aid buys you seconds; Combat Life Saver buys you minutes; the medics buy you hours and the doctor can give you days," said Command Sgt. Maj. Uriah Popp, Womack Army Medical Center senior noncommissioned officer, Fort Bragg, North Carolina. "We have to be able to sustain life from the point of entry through evacuation or delayed evacuation to get you to a surgeon to be able to have the patient survive the situation or the wounds to get them surgical intervention."

Popp was present as the Soldiers in the first course of Prolonged Field Care worked their culminating event Oct. 26 at Fort Riley's Medical Simulation Training Center.

The weeklong program enhanced the knowledge already learned from Advanced Individual Training at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, to provide medics with the ability to use equipment found in an aid station like ventilators, suction and whole blood drawing equipment, said Sgt. 1st Class Anthony Denning, noncommissioned officer in charge, Medical Simulation Training Center, U.S. Army Medical Department Activity.

"A lot of the concepts they receive here will help them in any scenario that they are in," Denning said. "A lot of it's based on the type of equipment they will have. But out in the field, they understand the lethal triad and how they need to set up and prepare their casualty to be received by an aid station."

The priority for the medics to learn was controlling patients from entering what they refer to as the "lethal triad."

"(The) lethal triad is a combination of coagulopathy, acidosis and hypothermia," Denning said. "That's going to lead to a quick fatality, which we are trying to prevent."

Popp said there was an Army identified gap for prolonged field care due to a loss of air superiority or evacuation platforms.

"A lot of the work for this course was done through Special Operations Prolonged Field Care working group," Popp said. "So, essentially what we did was take some components of the Special Operation Medic Course combined with the research and recommended protocols, procedures from the Prolonged Field Care working group and then current clinical practice guidelines for prolonged field care through whole blood administration … One of the things that we are working to, [with] the goals of the Military Health System, is to decrease morbidity and mortality on the battlefield."

Popp said of the Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom deaths through 2011, nearly 25 percent were deemed potentially survivable.

"So, it's like 964 patients deaths could have been prevented through proper intervention at either point of entry through the medic level," Popp said.

Since its inception in 2015, the program has been implemented at most of the direct reporting units of I Corps and the 18th Airborne Corps, and it is currently expanding through III Corps, Popp said.

"Prolonged field care, by definition, is holding a patient past the doctrinal timeline of two to four hours for priority patients," Popp said. "What it really gets after is mitigating the lethal triad. That's what's important, that's what's going to kill the patient. If you don't mitigate that, it decreases the prognosis of the patient."

TIP OF THE SPEAR

Fort Riley is one of the first locations within III Corps to receive this training, according to Denning.

"We are one of the facilities, one of the duty stations, who are getting a jump on it," he said. "We are trying to provide the 1st [Infantry Division] Soldiers with the knowledge they need when they get ready to deploy. I'm very proud and happy to be a part of it."

First Infantry Division Artillery physician assistant, Capt. Donnie Hawk, was on hand to witness the culminating event and said he is amazed at the training being offered to the Soldiers of the 1st Infantry Division.

"I just got back from Poland and the geographic spread of forces that we are potentially protecting or maybe even fighting (is great)," Hawk said. "To be able to get these guys up to speed, to be able to hold a casualty even longer definitely increases the warfighting functions and capabilities of the maneuver units. But it also sustains the fighting force a little longer to allow these guys to 1) more and 2) to save some lives."

Hawk said this level of training is usually reserved for senior NCOs or medics. He was pleased to see the lower enlisted getting the opportunity to increase their knowledge base with the training.

"It's great that we can get it to the lowest levels and prepare them for what may or may not happen in the future," he said. "As you can see here, we have three or four E-2s that are doing it, and doing well at it."

For 3rd Battalion, 66th Armor Regiment, 1st Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Infantry Division medic Pvt. Joshua Railsback, this was an opportunity to expand what he learned at AIT.

"I know during AIT we would learn how to take care of a casualty immediately, but afterwards if evacuation was delayed we essentially reevaluated vitals," Railsback said. "This helped elaborate what we needed to do after and kind of give us a baseline of what we need to do."

Railsback said the training made him feel more confident in his abilities to handle this type of situation. "I know before I felt like I could do it if I had to, but I wasn't the most confident," he said.

Included in the training was giving the medics the ability to transfuse whole blood into a patient, what Denning referred to as "a walking blood bank."

"If they have a casualty for an extended length of time, they can find a match," he said. "A donor that has the same blood type as the casualty ... can do a walking blood bank where they draw the blood and then can provide that to the casualty. Instead of just pushing fluids that may dilute the blood that is already in them, they will have blood to push back into the casualty."

CULMINATING EVENT

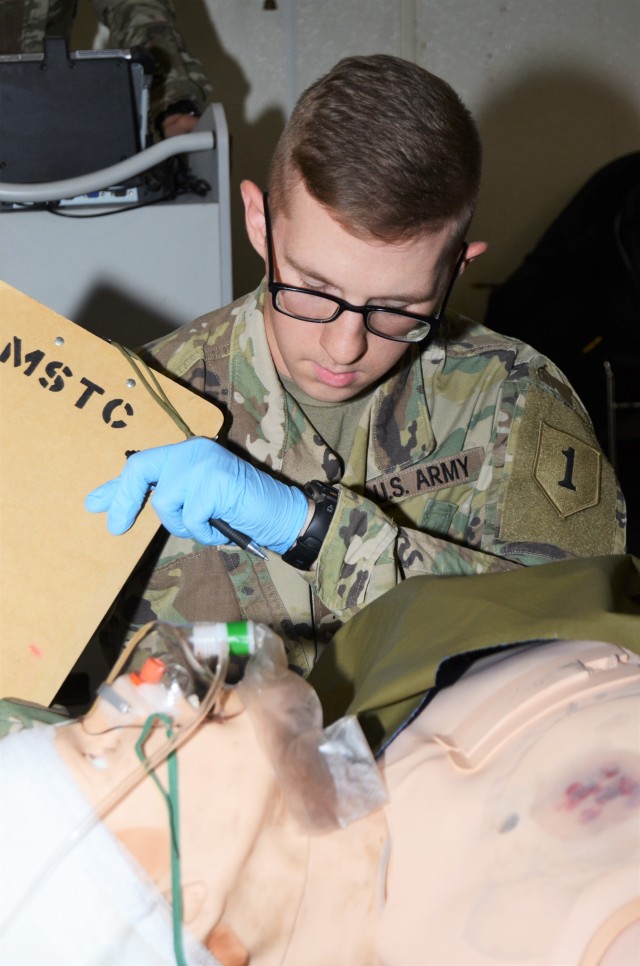

The medics entered the room with a mannequin on a litter as if the patient just arrived to the aid station. From there they re-evaluated the patient's condition and moved forward with treatment.

"It will already have some treatment done -- they are going to have to reassess interventions already done, vital signs and maybe if they are not satisfied with interventions already done, correct the interventions and make sure any life threats are addressed," Denning said. "And then they will start documentation of vital signs to make sure they are tracking trends.

"The difference between this and the normal scenarios we do is that the normal combat scenarios are hard and fast," he added. "We try to stress them. With this, it's more of an extended period of time. It might be hard and fast at the beginning, but they get into a routine, checking vitals and tracking trends."

The mannequin used for training is hooked up to a laptop from which an evaluator can control everything from breathing to making sound effects, as if the patient were coughing or moaning in pain.

As the evaluation went on, the medics were only able to get the vitals of the patient from the evaluator at the computer, as they are unreadable by their equipment.

If treatment procedures were missed or went unchecked for too long, the evaluator was able to simulate different conditions to make the patient worse, like collapsing a lung or having the patient's heart rate start to slow down.

The patient responded positively as treatments were administered, whole blood transferred and medications given.

For Hawk, the training aids were better than what he used when he first entered the Army, a fact that impressed him.

"I've been in for 13 years and in the day we had the 'Rescue Randy's'" he said. "Those were the big dummies that weighed 180 pounds. So you had to ask the instructor, 'do I see equal rise and chest fall, do I hear breath sounds,' those sort of things. To provide that feedback directly to the end user is amazing. The technology is insane."

Hawk, Denning and Popp all said they hoped the medics all left the training with greater confidence in their ability to perform the procedures to extend patients' chances of survival.

Social Sharing