Army materiel developers could learn a lot from the perspicacity and grit of one old man. The adage has it that the doctor who treats himself has a fool for a patient, but there's a long tradition of self-experimentation in science. Perhaps nowhere has it been so successful, if only after decades of effort, as it has been for engineer-turned-doctor Richard K. Bernstein, M.D., a Type 1 diabetic who has arguably broken more ground than anyone in history to help diabetics live normal lives, all because he used himself as a guinea pig.

The evidence could not have been more clear: After years experimenting with his diet and insulin regimen to level out his blood sugar, engineer Richard K. Bernstein saw the answer he was seeking to his ever-more damaging Type 1 diabetes. It included monitoring blood sugar closely, and minimizing fast-acting carbohydrates.

Diabetes had affected his health for so long, since age 11, that Bernstein, at age 35, set out to control the diabetes, which was making life miserable in so many ways. He looked and felt like an old man at what would seem to be the prime of his life, to be enjoyed with his wife, Anne, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, and their children--three at the time, all under the age of 9.

His moods fluctuated dramatically with his blood sugar levels, making him often irritable, prone to lashing out at work and at home. Fatigue was his norm. His kidneys had been damaged by high blood sugar. His vision had deteriorated. And there was the relentless uncertainty that comes with any chronic, life-threatening disorder. "You know, it's very frightening to not know your blood sugar and know you could die of a low blood sugar [episode] any time," he said.

By happenstance, he saw an ad in a medical laboratory trade journal he had been receiving, for a three-pound meter designed for hospital emergency rooms. The device gave ER staff a way to determine, when laboratories were closed at night, whether someone who appeared drunk was in fact having a diabetic crisis. It cost $650, more than $4,400 in today's dollars--a major investment compared with today's finger-stick blood glucose meters for daily use, which generally range from $15 to $30.

The only problem was that the meter was available at the time only to medical professionals. So Bernstein ordered it through his wife and set out to solve the most important problem he'd ever faced. "I said, well, I'm an engineer. If I knew what my blood sugars were, I could do something about them."

That was 1969, and Bernstein was, in effect, his own doctor in his quest to master his diabetes. For the first time, looking at seven or more blood sugar measurements a day, he could see his body at work, and it wasn't a pretty sight. Over the next four years, through experimentation, he developed a way to achieve normal, steady blood sugar levels, and it made all the difference, reversing most of the damage his elevated blood sugars had done.

DEFINING A NEW FRONTIER

His own physician said there was no reason for a diabetic to maintain normal blood sugars. But Bernstein saw, and felt, the results of his experimentation, felt the immensity of the weight lifted from him, and understood the potential power of his results for uncounted other diabetics struggling to survive, much less thrive.

He had no idea how hard it would be to persuade the medical community of this potential, the professionals who supposedly were dedicated to improving diabetics' lives. It would take a medical degree, a 560-page book and many more years beyond those for Bernstein to persuade even a minority of the diabetes specialists in this country that a carefully structured low-carbohydrate diet, in conjunction with multiple carefully timed insulin shots, can normalize blood sugar in Type 1 and many Type 2 diabetics. Perhaps just as important, it would also take thousands of diabetics essentially experimenting on themselves with Bernstein's guidance--and living markedly healthier lives as a result.

Now 84 and a practicing physician in Mamaroneck, New York, Bernstein has surpassed, by 43 years, what the average life expectancy was for a person diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at the time he was diagnosed. He is not disabled. Far from it. He sees patients four days a week, works out three times a week and maintains a passion for opera. "Vecchio e saggio," or "old and wise," was his response in Italian to the less colorful "How are you?" that opened Army AL&T magazine's conversation with him on May 24.

"Vecchio" because Bernstein figured out how to keep diabetes from cutting his life short. "Saggio" because he has learned so much about the modern practice of medicine: its institutional prejudices, professional self-interest and perverse economic incentives, Bernstein said--themes that cross over into the fields of science and engineering, not to mention government. And it's hard to miss the parallels with Army acquisition: bureaucratic intransigence, risk aversion, self-protection.

THE PHYSICS OF LIFE

Bernstein did not set out to be a doctor, or even an engineer. As a teenager, he wanted to study physics, not diabetes. An insatiable learner, he asked his high school science teacher for some summer reading, plunged into two books--one on quantum physics and the other on relativity--and was hooked right away. It was the "strange things that were involved that hook most people who go into physics," he said. "There were things that seemed to contradict everyday experience. And I wanted to study that."

He was on the right path for a while, a student at Columbia College, admitted two years below the minimum age. He loved physics and the company of physicists. His lab partner at one point was Gerald Feinberg, later the head of Columbia's physics department and the person who introduced the word "tachyon." A tachyon--from "tachys," the Greek word for swift--is a theoretical quasi-particle that moves faster than the speed of light and can travel backward in time.

Such mystery and complexity were precisely what Bernstein thrived on at Columbia--if only he could retain what he was learning from day to day. "I couldn't remember what I was taught in any of my courses. By the time I started the second year in college, I was taking graduate math courses. But again, I couldn't remember things." His thyroid gland, the engine of the human body, was not producing enough thyroid hormone.

Thyroid disorders are second only to diabetes in the United States among conditions affecting the endocrine system, the group of glands from which the body gets hormones that regulate growth, function and nutrient use by cells. An estimated 20 million Americans have a thyroid disorder, although as many as 60 percent of them don't know it, according to the American Thyroid Association. It is common for someone to have both thyroid disease and diabetes.

With classmates like Feinberg, Bernstein thought, "I can't compete with these people. Here I was, sleeping through classes. I was missing exams because I'd sleep until 10 o'clock in the morning. So I switched to engineering, figuring it would be less demanding." Bernstein was in Columbia's "professional option program," whereby he could finish his last year of college while taking his first year of engineering school.

By a stroke of luck, a doctor suspected that his thyroid was at the root of his problem. "So they put me on thyroid replacement, and I suddenly woke up. I got all A-pluses for the rest of my engineering education."

He received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Columbia College and a Bachelor of Science from Columbia Engineering, and set out to make a living.

EARLY GLIMMERS

With his training in math and engineering, Bernstein's first jobs were in what is now known as systems engineering. He worked for a housewares company that had a warehouse in Massachusetts and a showroom in New York City, taking orders mailed to the New York office by salesmen across the country. The New York staff would type up the orders and mail them to Massachusetts, where warehouse personnel would ship the products and then mark on the forms mailed to Massachusetts how much they'd shipped, how much was back-ordered and so on. The completed forms were mailed back to New York.

Photocopiers as we know them today did not exist, so if some of those forms got lost in the mail, they were gone. Bernstein had an idea to modernize this process.

As a computer maker, "IBM was brand new. Punch cards were brand new. Paper-tape teletype was old; that was how they sent telegrams," he said. "What I set up was a system where people in New York would type up punch cards and put them in a machine that converted them to paper tape, [then] run the paper tape through the teleprinter." That would simultaneously transmit the information to Massachusetts and print it in New York on the teleprinter, providing hard copies of the information to both locations.

"Plus, the tape up in Massachusetts could be converted to IBM cards and they could then, when they made a shipment, type into the cards the shipment information, convert them back to tape and send the tape to New York. It was sort of very early automation … the only company in the country that had bidirectional, long-distance information transfer."

The company did not have the progressive management Bernstein was looking for, however, so he looked elsewhere, hoping to get back into science. He took a job in the medical equipment field, where he was responsible for product development, among other areas, and applied his training and expertise to a number of products, some of which are still on the market 60 years later. For example, one was a stain to pick up microscopic abnormalities in urine, another a centrifuge for blood testing in doctors' offices. Bernstein was doing what he enjoyed, and he had a lot to show for it--none of which would keep him from "dying of the complications of diabetes."

A HANGRY MAN

His main problem was frequent dips in blood sugar, "causing me to get into all kinds of trouble because your behavior gets distorted. You get easily frustrated. You can get angry at people. You could lose your temper. It's like being drunk. So, if my blood sugar were low and if my boss was wrong about something, I'd yell at him. If my blood sugar were normal or high, I'd tolerate his mistakes."

Bernstein's wife and children suffered the same volatility. "The problem was terrifying my family at home," he said. So in 1969, when he saw that ad in the trade journal for laboratory equipment for a three-pound meter designed for hospitals to distinguish the intoxicated from the diabetics, he went for it. The blood-testing process was far from elegant--"you had to rinse off the blood after a minute and then blot the [test] strip, so I had to carry a little squeeze bottle of water with me, but it was easy enough to get accurate results."

Over the next three years, Bernstein took careful notes on how his blood sugars varied with exercise and insulin intake, on a cheap, pocket-sized notebook with perforated pages. He increased his daily insulin shots from one to two. The sharp highs and lows smoothed out somewhat, but his health was no better, although his physician saw nothing remarkable and said he was doing well.

Over the next year of his experimentation, measuring his blood sugar five to eight times a day, he changed one aspect of his routine every few days--what he ate, when he took insulin shots, his dosages--and maintained the changes that resulted in normal blood sugar, discarding those that didn't. He found, for example, that one gram of carbohydrate raised his blood sugar by 8 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), and that one-half unit of the beef-pork insulin he was taking lowered it by 15 mg/dL. He was on his way to the breakthrough he was looking for.

"It was about two years after I got my blood sugar straightened out and started to see my complications getting better. I was actually sitting on the toilet, and was thinking that I felt like I had escaped from a concentration camp and that there were millions of people still prisoners, whose lives were on the line every day. That's the case with Type 1 and many Type 2 diabetics, because they could drop dead of very low blood sugar or even go very high" and develop life-threatening diabetic ketoacidosis.

"So I had to get doctors interested in this better mousetrap. I decided that I was going to try to convince the physicians who attended the [medical] conventions that they should have their patients measuring their blood sugars and do the other things that I had worked out."

As convinced as Bernstein was of the benefits of self-monitoring, he was astonished to find not a single physician who wanted to be convinced. Having patients check their own blood sugar was an unwelcome concept to the established experts in endocrinology, as his very low-carbohydrate dietary solution would later prove to be.

His first target of persuasion was his own doctor, who was president of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Founded in 1940 by 26 physicians as a professional medical organization, the ADA had only recently, in 1970, opened its membership to the general public. Now the organization describes itself as "a network of more than one million volunteers, a membership of more than 500,000 people with diabetes, their families and caregivers, a professional society of nearly 14,000 health care professionals, as well as more than 800 staff members." Its stated mission is to "lead the fight against the deadly consequences of diabetes and fight for those affected by diabetes," by funding research, delivering services, providing "objective and credible information" and being a voice for "those denied their rights because of diabetes."

Bernstein tried to get across three points. "One, I was taking a shot before every meal and also a shot of long-acting insulin twice a day, five shots a day," to which he said his doctor responded, "It's enough trouble to try to get a patient to take one shot a day. No way am I going to waste my time trying to get someone to take five shots a day."

Point No. 2: "I said, 'Well, you know, the literature on animals shows that you reverse the diabetic complications if you normalize their blood sugars.' He says, 'Yeah, but you're not an animal.' And I remember saying to him that Einstein said that the laws of nature remain throughout the universe."

Point 3 was the urgent need for patients to measure their own blood sugars. His doctor's objection, Bernstein said, was purely one of self-interest. "He said, 'I certainly am not going to let them measure their own blood sugars because they come to see me once a month to get a blood sugar. If they can do it themselves, I'd never see a patient.' " Not until 1980 would finger-stick glucose meters be available to the general public for accurate self-testing of blood sugar.

Bernstein knew that he'd have to communicate with the medical establishment the way they communicated with one another, by getting published. "I didn't know how to write a medical article, but the people who made the blood sugar meter had a medical writer on their staff, and he guided me. We put together an article that was about 20 pages long and was scientific-looking. It used medical terminology and so on." As this was before computers made it easy to type something and print it in multiple copies, Bernstein paid $1,000 to have it typeset by hand for reproduction.

He still has the rejection letters. "I submitted it to a number of journals, a couple of journals published by the American Diabetes Association and also the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Journal of Medicine."

"I wrote this really as a step-by-step to what patients should do. I didn't put it together, as 'Here's the evidence,' but it was my assumption that doctors would jump to normalize blood sugars."

THE RIGHT TO BE NORMAL

A central principle of Bernstein's solution for diabetics is that they have "the right to normal blood sugars like a nondiabetic," such that even when they eat, their blood sugar remains constant at a healthy level.

Professional self-interest is the only reason that Bernstein can see for major medical organizations like the ADA to set a standard for blood sugar in diabetics that is higher than what the same organizations know is normal. The ADA's desirable blood sugar level for diabetics is 70 to 130 mg/dL before meals, and less than 180 mg/dL after meals, versus Bernstein's target constant blood sugar of 83 mg/dL for adults, in the 70s for children before puberty and 65 for pregnant women.

The likely reason for the ADA standards is that doctors want to hedge their bets and avoid the risk that a diabetic patient could die from hypoglycemia, or too-low blood sugar, Bernstein said. "If they go too low, the doctor is afraid of getting sued, so he doesn't want any part of it." Whereas, he said, if the patient suffers diabetic complications with blood sugars in the ADA's target ranges, there are long-term expected consequences of their disease that would never justify a lawsuit. If a patient with chronically high blood sugar gets a foot amputated because of a nonhealing ulcer, insurance will pay for it and the doctor won't get sued. If, however, in trying to keep a patient's blood sugar normal, a diabetic dies from a prolonged very low blood sugar level, the doctor can be sued.

The issue of carbohydrate reduction as a means to prevent wild blood sugar swings is equally important to Bernstein, and one on which he continues to assail the much larger forces of the ADA and the food industry.

Whereas Bernstein, based on his experimentation, has arrived at maximum limits on carbohydrates that diabetics should observe in order to maintain normal blood sugar, the ADA is nonspecific in its dietary guidance. Rather, it offers a generic statement on the many choices diabetics face in deciding what to eat and defers to the diabetic to make the right choices in consultation with their health care providers.

"Carb counting may give you more choices and flexibility when planning meals," the association states on its website. "It involves counting the number of carbohydrate grams in a meal and matching that to your dose of insulin. With the right balance of physical activity and insulin, carb counting can help you manage your blood glucose. It sounds complex, but with time you and your diabetes care team can figure out the right balance for you," the website states.

The ADA's bottom-line position on the right diet for diabetics? "There isn't one. At least not one exact diet that will meet the nutrition needs of everyone living with diabetes. Which, in some ways, is unfortunate. Just think how simple it would be to plan meals if there were a one-size-fits-all plan that worked for everyone living with diabetes, prediabetes, or at risk for diabetes. Boring, yes, but simple!

"As we all know, it's much harder than that. In the long run, an eating plan that you can follow and sustain and that meets your own diabetes goals will be the best one for you."

ONE BRIGHT LIGHT IN THE DARK

By 1975, the only encouragement Bernstein had received for his efforts to promote normalizing blood sugar was from Charles Suther, in charge of marketing diabetes products for Ames Division of Miles Laboratories, the company that made the blood glucose meter he had bought. Suther also hand-distributed Bernstein's rejected article to diabetes researchers and physicians around the United States.

Suther arranged for free testing supplies to support the first of two university-sponsored studies in this country, which demonstrated that normalizing blood sugar levels could reverse early complications in diabetic patients. Those studies led, in turn, to the universities sponsoring the world's first two symposia on blood glucose self-monitoring. Bernstein was becoming better-known and received invitations to speak at international conferences on diabetes, though not in the United States. The ADA nevertheless continued to block blood sugar self-monitoring.

Frustrated that self-monitoring was still not accepted and that he could not get published, Bernstein reluctantly pursued another path. He hoped that an M.D. degree would enable him to publish. So, in 1977, he quit his job, took premed college courses, got high grades on the Medical College Admission Test and entered medical school.

Six years later, he opened his practice in Mamaroneck, a suburb of New York City, determined to do things differently. Instead of spending an hour or less with a new patient, Bernstein's initial evaluation and training spans three days. Nowadays, he makes himself available to patients not only at his office, but through free monthly teleseminars and videos in which he answers questions sent to him from around the world.

Spending those three days with new patients enable Bernstein to address other issues that may affect their blood sugars. "They may have eating disorders. They may have a neuropathy of the digestive system, which is very common in diabetics, called gastroparesis. They could have other things that screw up the diabetes, like infections or the need for steroids and so on. Almost every patient presents with new variations, new problems. I'm trying to keep their blood sugars in a very narrow, normal range."

Now the author of nine books, Bernstein is best-known for the 560-page "Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Solution: The Complete Guide to Achieving Normal Blood Sugars," originally published in 1997 and updated in 2011. His book has become a lightning rod for patients and families who are desperate, as he once was, to not be at the mercy of diabetes. As the title indicates, it goes into great detail on how diabetes affects the body; how diet, exercise and insulin of various types, for example fast-acting versus slow-acting, affect blood sugar; and the optimal times to measure blood sugar and take insulin (a minimum of five shots a day for Type 1 diabetics; for Type 2, anywhere from none to five a day depending on the severity of their diabetes).

The book also goes into candid detail about the many medications for treating Type 2 diabetes, describing the appropriate circumstances for their use as well as their values and shortcomings and modes of use.

Bernstein's strict emphasis on maintaining a very low-carbohydrate diet--an average of 30 grams a day for a 140-pound person--is central to keeping blood sugar at normal levels. He has found, from his own experience and that of his patients, that higher amounts of carbohydrates rapidly raise blood sugar above what is normal and healthy.

That means, for example, avoiding all foods with added sugar or honey; all foods made from grains and grain flours such as breads, cereals, pasta and rice; all starchy and high-carbohydrate vegetables such as potatoes, corn, carrots, peas, tomatoes and most beans (as opposed to zucchini, cucumbers, broccoli, cauliflower and other vegetables that contain mostly complex carbohydrate that's harder for the body to break down); and, with very few exceptions, all fresh or preserved fruits and fruit juices. It also means avoiding dairy products except for butter, cream, cheeses and full-fat yogurt; the higher the fat content of dairy products, the lower the carbohydrate content.

THE LAWS OF SMALL NUMBERS

Key to Bernstein's approach to managing blood sugar, and a reflection of his systems engineering perspective, is what he calls "the laws of small numbers," which basically look at the management of blood sugar as an imperfect system because there are variables in it such as what you eat and how much insulin you inject or produce. The laws of small numbers can be seen as a corollary of the "fail early" principle in Army experiments with warfighting technologies.

The point is, Bernstein said, "If inputs are imprecise, the outputs will be imprecise, and the errors in the outputs will be greater for large inputs." In other words, he said, "Big inputs, big mistakes. Small inputs, small mistakes. I'm sure it applies to any system where there's any degree of uncertainty of your inputs, where you can't be precisely on the nose."

Say, for example, that a diabetic who takes insulin is trying to estimate the amounts of carbohydrates to eat. The diabetic is having 100 grams of carbohydrate, each gram of which will raise blood sugar by 10 mg/dL. One unit of insulin will lower blood sugar by, say, 50 mg/dL. Thus, if the diabetic is going to eat 100 grams of carbohydrates, that will raise blood sugar by 1,000 mg/dL, requiring 20 units of insulin.

But the carbohydrate estimate could be way off from the actual amount, Bernstein said. "Let's say that you take a medium-sized apple. Depending upon how old it is, how long it's been sitting on the counter, what brand, what kind of apple it is, what form, what the weather conditions were for its growth, you can probably be off by, let's say, 40 percent on the amount of carbohydrate in that apple. And you're looking at other things that you're eating in that meal to get that 100 grams."

If the estimate is off by 40 percent, that translates to 400 mg/dL on the blood sugar measurement. "But you're treating it with insulin as if it were 1,000. It could be 1,400, and it could be 600. So, what you're going to do is possibly be 400 mg/dL off on your blood sugar after that meal."

In addition to which, the insulin introduces its own variability, he said. "If you're using ultra-rapid insulin, which is what the doctors like nowadays, you have a very sharp peak of insulin activity. If you're using rapid-acting carbohydrate … you get a sharp peak in blood sugar rise, and you're trying to match in time the sharp peak from the insulin with the sharp peak from the rise.

"Whereas if you're using small amounts of slow-acting carbohydrate and small amounts of slower-acting insulin, you end up with a shallow peak and a shallow peak, and you have to match those. And they're not peaks, they're just shallow bumps. It's much easier to match two shallow bumps in time than two sharp peaks."

The laws of small numbers apply to any number of situations involving the day-to-day, hour-to-hour management of blood sugar, Bernstein said, and should guide the diabetic patient's calculations of "if x, then y."

This is yet another area in which Bernstein's approach to diabetes differs sharply from the established advice, he noted. "What do you do if your blood sugar gets too low? The medical profession may tell people, eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, which will have an unpredictable effect on blood sugar, [the ingredients] being both rapid and slow acting. It'll start maybe in 10 minutes, 15 minutes, but it'll keep working for hours." Bernstein advocates the use of measured amounts of pure glucose--liquid glucose, if possible--to rapidly raise blood sugar by a predictable amount if it's too low.

EXPANDING THE DATA

The letters following "M.D." after Bernstein's name--F.A.C.N. (Fellow, American College of Nutrition), F.A.C.E. (Fellow, American College of Endocrinology) and FCCWS (Fellow, College of Certified Wound Specialists)--attest to his advanced work.

"I've experimented on myself, but I've learned all kinds of new tricks from working with patients," he said. "I'd look at their blood sugars for one or more weeks, look at their insulin doses and when they took it, how much they took, when they ate, etc. I ask the patient to eat the same meal every day while I'm experimenting with them so that I can get consistent results."

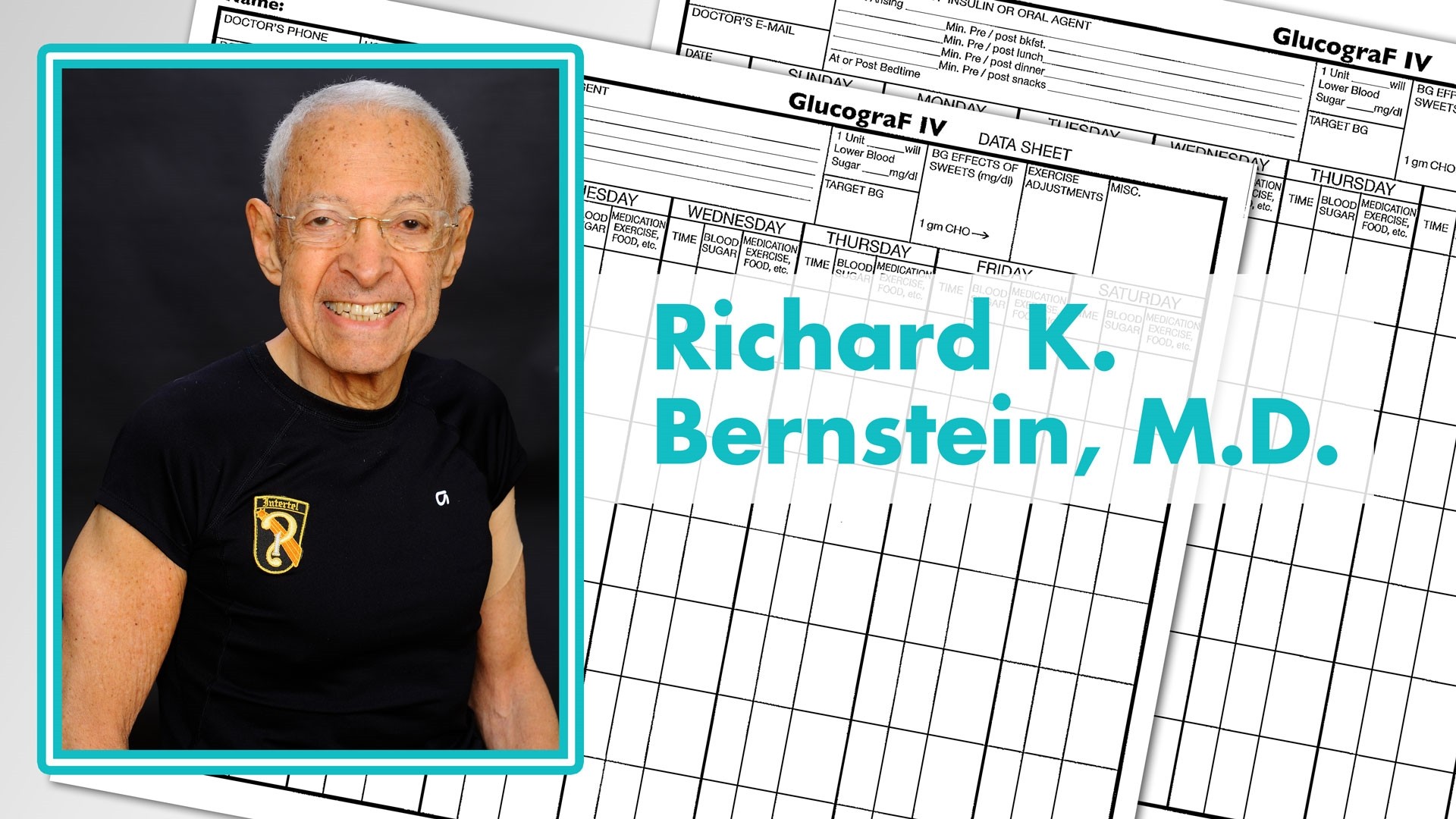

Disposable pocket notebooks wouldn't work for this level of data collection and comparison, so, ever the engineer, Bernstein designed a chart he calls the Glucograf for patients to enter data that he could readily interpret. The chart records time, blood sugar, food, medication and exercise for each day of the week. "I needed a format that would enable me to rapidly figure out what's happening to a patient." He uses it for himself, too.

The data from patients has taken on a life of its own with the formation a few years ago of TypeOneGrit, a Facebook group of about 3,000 Type 1 diabetics, or parents of Type 1s, who have read "Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Solution" and are currently following his very low-carbohydrate protocol to normalize blood sugars. The discussion and advocacy group formed around a shared conviction that the protocol works, and the impassioned belief that it can work for other diabetics to relieve the havoc and dismay that uncontrolled blood sugar can wreak in their lives.

"We believe that type 1 children (as well as adults) are entitled to the same normal blood sugars as non-diabetics," TypeOneGrit's Facebook page states.

Most of the diabetics represented in TypeOneGrit use continuous glucose monitors, which employ fine sensor fibers placed in the skin to measure blood sugar. The data can go to a cellphone and be uploaded to a computer.

The data that TypeOneGrit members have generated are now national news. Nearly 50 years after Bernstein began experimenting on his own blood sugars, the journal Pediatrics on May 7 released an article, "Management of Type 1 Diabetes With a Very Low-Carbohydrate Diet."

The finding was "Exceptional glycemic control of type 1 diabetes without high rates of acute complications may be achievable among children and adults with a very low-carbohydrate diet," according to an online patient survey. The researchers, led by Belinda Lennerz, M.D., Ph.D., and David Ludwig, M.D., Ph.D., of Boston Children's Hospital, reviewed data provided by the physicians of 316 TypeOneGrit diabetics, 42 percent of them children. All of the survey respondents had followed Bernstein's diet for at least 90 days, consuming an average 36 grams of carbohydrates per day (ranging from 30 to 50 grams), or less than 5 percent of total calories.

Carbohydrate intake was the only predictor of their A1C blood sugar levels. The survey group had an average blood sugar of 103 mg/dL and an average A1C (a longer-term measure of blood sugar) of 5.67 percent. Nearly all, 97 percent, bettered the ADA's targets for blood sugar. Significantly, the very low intake of carbohydrates had no adverse effects on the children's growth, as measured by normal height for their ages.

"It's hard for me as a single person, unfunded, to do a study," Bernstein said. "If it weren't for this group that materialized on Facebook--a mother finding my book and a father who's a physicist used it to treat their newly diagnosed son, who had previously been put into big trouble because of conventional medical treatment; he turned around and started growing and having normal blood sugars--if they weren't so excited about this and organized this group, this paper wouldn't have come out."

VINDICATION? NOT YET.

The researchers who conducted the study are now calling for controlled clinical trials of the very low-carbohydrate protocol to normalize blood sugar levels, which would seem to vindicate Bernstein's hard-fought convictions. The study is unquestionably a big boost to his work, but hardly the last word.

This one published article does not mean, Bernstein said, that it's time to sit back and say he's done what he set out to do. "I say it'll be vindication when the doctors start changing. I know of a number of Type 1 diabetic doctors who are using my book to treat themselves, but not to treat their patients because they don't have the time to spend with the patients.

"I'm waiting to see what happens as a result of this article. We might get more attention. I'm anxious to find a large medical practice that has a lot of patients, where paramedical people can be used to teach them and train them, because doctors can't afford to do this."

The U.S. may not be the best test bed for broader experimentation of Bernstein's approach, he said. "Here it's very hard--[there's] a lot of prejudice against doing anything significant. The doctors are so interested in protecting themselves that it might be smart to look to another country, like China, where there's a huge epidemic of diabetes due to overeating. They don't know how to treat it, but their health care system is well-funded."

Nor is Bernstein inclined to retire and write the autobiography of a determined insurgent who challenged long-established institutional health care practices on behalf of some 30 million Americans--422 million worldwide--living with a potentially fatal disease.

Diabetes is the field he knows the best. "I would much rather be a physicist, and I'm 84 years old. I'd rather not be working so hard. I like sailing; I'd rather be sailing. But I'm stuck. I have to continue. I have an obligation to the patients who didn't know what I know."

He has "absolutely not a doubt" in the science of what he's doing "because I see the results. I see it every day. Patients are getting better."

MS. MARGARET C. ROTH is an editor of Army AL&T magazine. She has more than a decade of experience in writing about the Army and more than three decades' experience in journalism and public relations. Roth is a MG Keith L. Ware Public Affairs Award winner and a co-author of the book "Operation Just Cause: The Storming of Panama." She holds a B.A. in Russian language and linguistics from the University of Virginia.

Related Links:

Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Solution

Healthline.com interview with Dr. Richard Bernstein

Management of Type 1 Diabetes With a Very Low--Carbohydrate Diet

How a Low-Carb Diet Might Aid People With Type 1 Diabetes

Study Investigates Very Low-Carb Diets for Type 1 Diabetes

Why This Former Army Captain With Type 1 Diabetes Eats Low-Carb

This article will be published in the July - September 2018 issue of Army AL&T magazine.

Sigma Nutrition Podcast: SNR #186: Dr. Jake Kushner, MD -- Nutrition for Type 1 Diabetes

Related Links:

Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Solution

Study Investigates Very Low-Carb Diets for Type 1 Diabetes

Why This Former Army Captain With Type 1 Diabetes Eats Low-Carb

Social Sharing