"You're not smart enough to be a doctor."

That statement, spoken by Daniel Cash's mother when he was 10, became the mind echo that motivated him to prove her wrong.

Now a doctor and a lieutenant colonel serving as the deputy commander for Clinical Services at Kenner Army Health Clinic, Cash said a childhood accident was the impetus for his desire to practice medicine.

"When I was 10, I crashed a moped into a house when the accelerator got stuck," he said, "and I almost died."

He was rushed to the hospital by ambulance and monitored for 24 hours. In those days - the early '80s - CAT scans weren't readily available at most medical facilities, so Cash said he was fortunate they kept him for monitoring because he had an undiagnosed subarachnoid hemorrhage, where there is bleeding in the space between the brain and its outer tissue.

"I've been told I went a little crazy in the hospital, and they had to do an emergency burr hole in my head to release pressure," he said. "After I recovered, that's when I knew I wanted to be a physician. However, my parents didn't think school was important, and when I told them, that's when they said I wasn't smart enough."

Reflecting on the moment, Cash said he didn't think the comment was meant to hurt him but had more to do with their life situation. Since his parents didn't push education and his family was very poor, advanced schooling was hard to fathom - and a run at a medical degree clearly pie in the sky.

"It was an issue of poverty for sure. The way they saw it, I would never have enough money to pay for school," he mused. "That made education a luxury ... and they didn't care about that. It was all about work.

"I don't think my mom even remembers what she said," Cash continued, "but when you're a child you always remember a putdown. That kind of thing sticks with you."

Painting an even broader picture of his childhood, Cash said his family was continuously in need of an immediate paycheck and at times struggled to keep a roof over their head. When he was 14, the family moved from their home in South Carolina to Homestead, Fla., where his father had a job lined up as a correctional officer. He was fired two months later.

"We relocated to Fort Lauderdale where my father continued to look for work because there were no jobs available in Homestead," he said. "We were homeless for 2-3 weeks, and we sort of lived in a park; then we lived in a shelter for two months before my parents got enough money for a place to live."

Despite his tough childhood, Cash - the fifth of six children - was the first in his family to graduate high school. While he was anxious to begin his medical school journey, the first order of business was to get a job and earn some money. A year later, he applied for financial aid for advanced schooling and was told he had "made too much money" as a landscaper to qualify for the assistance. So, he put his dreams back on hold and returned to the blue collar grind.

"Over the next 9-10 years, I worked at the same job," he said. "In the evenings, I ran orders for places like Pizza Hut and Dominos hours after an already full day of landscaping."

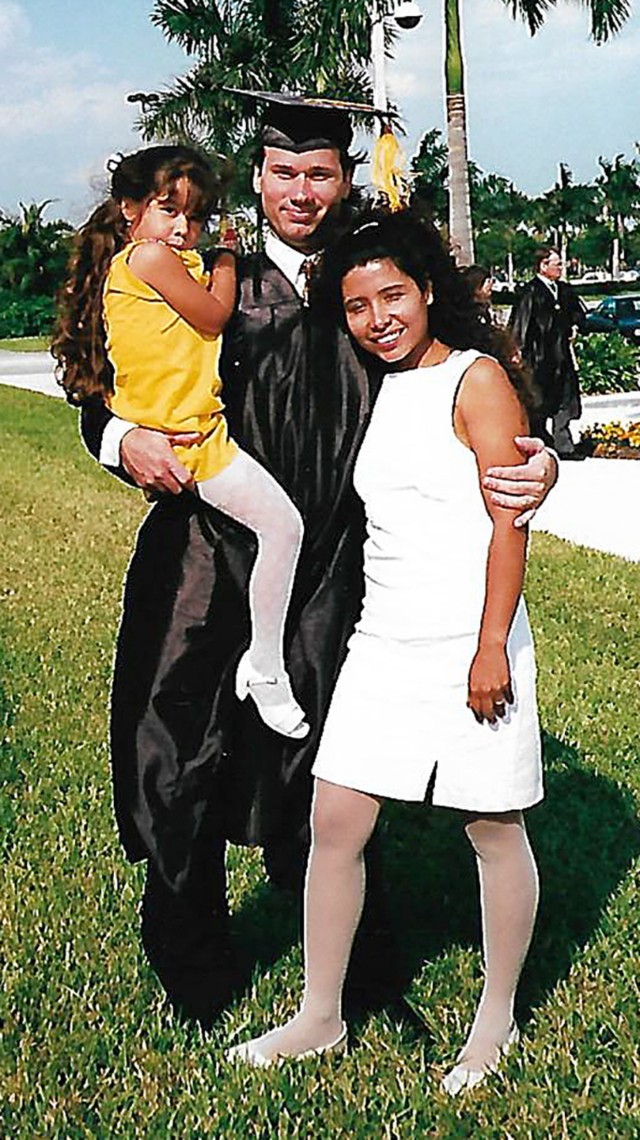

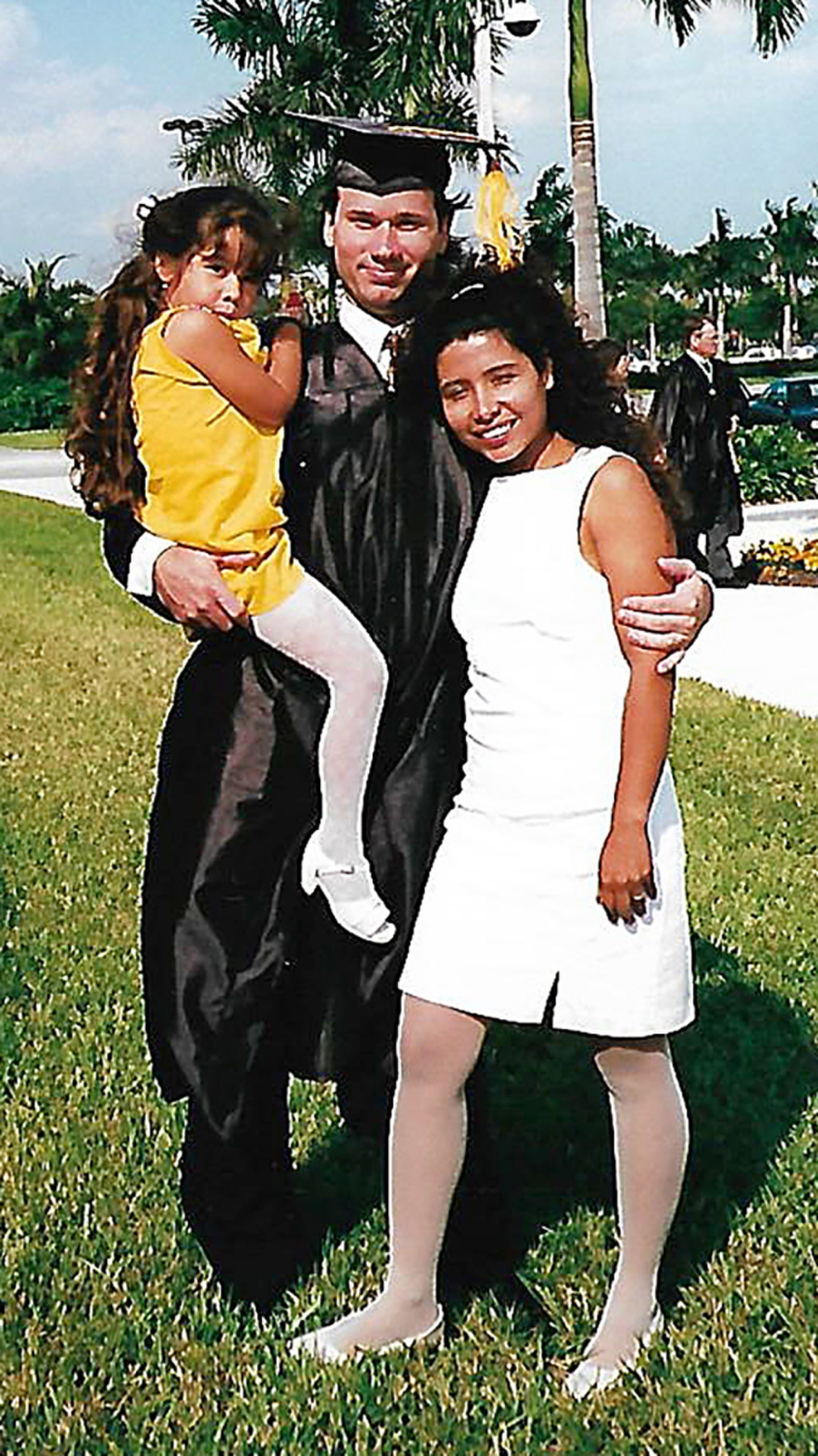

During those years, Cash married Enereida, an immigrant from Panama. When their daughter was born, his college aspirations returned with a fervor. He enrolled at a community college and worked a full-time job while also juggling his undergraduate coursework. He managed to earn a bachelor's degree in 3 years by increasing his credit hours each semester. After he graduated, he was accepted into medical school.

"Throughout this process, my wife was pitching in big time. She was working full time while also taking care of our daughter," Cash said. "She worked as an au pair so it was great because our daughter could go with her and grow up and play with those kids."

Despite earning mostly A's and a few B's and maintaining at least a 3.5 grade point average, Cash said he couldn't shake the nagging suspicion that he wasn't good enough to follow such dreams.

"The thought still lingered in the back of my mind; that I wasn't smart enough to be a doctor," he said. "Going through it, I wondered 'am I really able to do this?' In a lot of ways, I still saw myself as the blue collar worker landscaping under the hot sun and doing back-breaking work. How could I become something totally different?"

A lucky break from the draining effects of constant work and seeking loans to keep his dream alive came in the form of a Health Professional Scholarship Program offered by the Army. It would pay for his medical school on top of a monthly stipend. He signed on, and reaped the reward of the free ride through the remaining three years of medical school, after which there would be a three-year service obligation.

Cash did his residency at Womack Medical Center, Fort Bragg, N.C. Other highlights of his now 13 years of military service include a squadron field surgeon gig while deployed to Iraq; a stint as 108th Air Defense Artillery Brigade surgeon; and several postings as a family practice or primary care physician in Army clinics.

In reflection, Cash realized he had never been in doubt that he had signed up for the long haul.

"I did a lot of stuff (hard labor) over the years and didn't have much to show for it," he said. "I didn't want to do my time in the Army and not have anything to show for it.

"So, I tell anyone who comes through Kenner and is thinking about getting out to remember things like the great military retirement plan," Cash continued. "You're going to be working most of your life. What makes it easier, in my opinion, is working toward something. To be able to retire after 20 years is worth it, and some can have a full second career after that."

There are moments along the path he has traveled, Cash said, when it felt like a dream.

"I wondered how I was doing it - how I was attending school, making good grades," he said. "But here I am, 13 years later, and I've been working up the chain. I've done ... pretty well."

Now, Cash knows his mother and entire family are proud of what he has made of his life. To this day, his younger sister uses him as an example where she works.

"My sister graduated high school after me, the second one in my family to do so," he said. "She's now a police officer, and when she arrests someone and they try to make excuses about being poor and having to make a living, she tells them about me and how I became a doctor. She doesn't let anyone use being poor as an excuse. She says, 'If (Cash) could do it, anyone could.'"

And it seems as though Cash's daughter, Maria, will be walking in his footprints. She's set to attend his civilian medical school alma mater - Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine - at the end of July. She's also using the same military scholarship program her father did but will contribute her skills to the Air Force.

In her formative years, while he was going through undergraduate coursework, medical school and his residency, Cash said she was always interested in what he was learning about.

"One day while in first grade, Maria came home crying because other kids made fun of the drawing she made for show and tell," he said. "She drew a picture of a brain with all the optic nerves coming out, the circulatory system and a bladder with the kidneys. The kids were laughing because the bladder is where the urine comes out.

"I told her she shouldn't be upset because the children did not understand all the stuff she did," Cash continued.

When Maria told her father she wanted to be a doctor, he recalled saying, "You can be whatever you want to be. You can do anything."

Social Sharing