WASHINGTON -- It is 100 years to the day, June 26, 1918, since an obscure wood 50 miles from Paris, the Bois de Belleau, was captured by U.S. forces in a protracted battle of WW1. During those weeks the wood had become a focal point of American military hopes, an early and vital display of the American Expeditionary Force's capability on the battlefield. The bloody encounter occupies a special place in the annals of U.S. military history. Patrick Gregory looks at what happened there and asks why the battle still stands out.

In late April 2018, a photo opportunity featuring the presidents of the United States and France and their wives planting a tree was beamed across the world. What seemed to attract as much publicity at the time was the fact that the young tree in question was removed soon after the ceremony, taken into temporary quarantine. What achieved less attention was where the sapling had come from or why -- Belleau Wood.

As with most such scenes of slaughter of the First World War, the Bois de Belleau is as quiet now as it doubtless was before the fighting which erupted there in June 1918. And that fighting was brutal. What happened there was an important moment in the contribution of the United States in the First World War. It was also an important moment in the development of the U.S. Marine Corps.

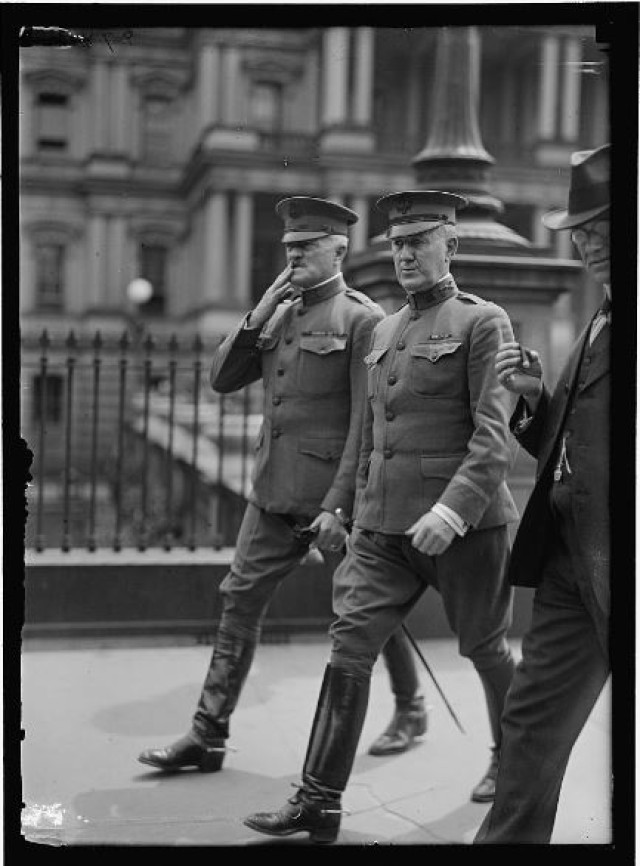

By May 1918 the U.S. had been a combatant in Europe for over a year; yet American troops, still arriving in France, had to date only played a supporting role. That was all going to change. American Expeditionary Force commander John Pershing had stubbornly resisted Allied efforts to co-opt his men -- a regiment here, a regiment there -- to add to their own ranks, remaining determined to train and assemble a fully-fledged army of his own.

The moment of truth now arrived to test those men in battle: 28 May 1918, the first full U.S.-led offensive of the war. Led by Pershing's trusted First Division, the 'Big Red One' under Robert Bullard attacked at Cantigny in northern France, 20 miles from Amiens. Of limited strategic value, perhaps, but the three-day battle was a success, demonstrating that the Americans could fight. It was a shot in the arm for the AEF, a much needed psychological boost after all the months' waiting.

However, of more immediate concern to the Allies was a new and deadly enemy offensive which had been unleashed during this time 50 miles south-east: one cutting easily through Allied lines and driving further south towards the river Marne, leaving German forces within striking distance of Paris.

On May 30 two separate American divisions, the 2nd & 3rd, were ordered into the Marne area, arriving from different directions east and west. A machine gun battalion of the latter secured the south bank of the river at the key bridgehead of Château-Thierry, as other of their number began to take up position.

But the main action of the weeks ahead would lie north-west of the town, involving men of the 2nd Division; in particular, two of their regiments, a brigade of Marines led by Pershing's old chief of staff James Harbord. It would be their efforts to secure a woodland there that would capture headlines, helped in part by the purple prose of journalist Floyd Gibbons.

Belleau Wood was barely more than a mile long and half a mile wide, yet it would cost many lives to capture and would be reported across the world. "It was perhaps a small battle in terms of World War I," says Professor Andrew Wiest of the University of Southern Mississippi, "but it was outsized in historic importance. It was the battle that meant that the U.S. had arrived."

Yet as operations go -- as brave and resolute as the troops were throughout -- it was poorly planned and badly commanded, certainly in its opening phases. After adjacent areas were captured on the morning of June 6, the decision was taken to advance on the wood that afternoon from two directions, west and south. The former was led by a battalion of 5th Marines under Benjamin Berry; the southern attack undertaken by Berton Sibley's battalion of 6th Marines, supported on their right by 23rd Infantry from the division's other regular army brigade.

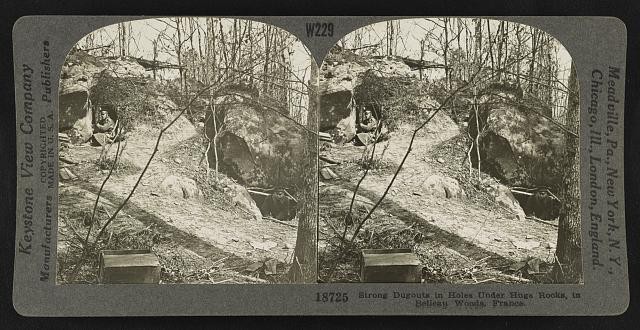

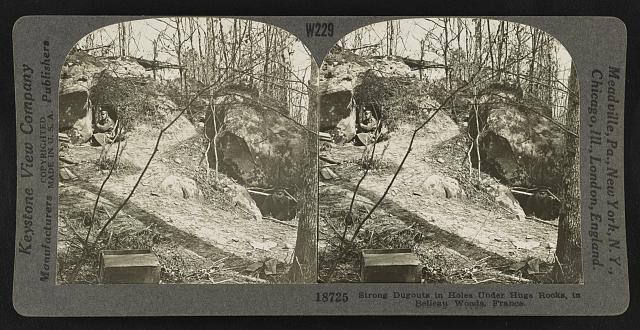

But little reconnaissance had been carried out in advance as to what to expect when they got there and only scant artillery fire was laid down beforehand. Inside, German machine gunners had taken up positions in defensive holes, behind rocky outcrops and shielded by dense undergrowth. Worse, the Marines now advanced towards them in rank formation over the exposed ground outside, with Berry's western advance particularly exposed. They were slaughtered. By nightfall 222 were dead and over 850 wounded.

Bloodied but remaining focused on the task, the men went again the next day. And the one after that. Yet little headway was made. An intense 24-hour artillery barrage was belatedly ordered, followed by yet another assault. Headway was finally made but casualties continued to mount as the German troops clung on in the farthermost reaches of the wood. The 7th Infantry from the neighboring 3rd Division was called in for some days to help lighten the load.

The fighting labored on for three weeks and in its final stages, foot by foot, hand to hand, it intensified in savagery. Artillery shells and guns now gave way to bayonets and "toad-stickers," 8-inch triangular blades set on knuckle-handles, as the Marines slashed their way through the last of their enemy. But finally word came through on the morning of June 26 from Major Maurice Shearer: "Belleau Wood now US Marine Corps entirely."

As the story goes, German officers, in their battle reports, referred to the Marines as Teufelshunde "Devil Dogs"; and journalist Floyd Gibbons also helped, singling out one gunnery sergeant in dispatches as "Devil Dog Dan." Either way, the name and image stuck and went on to become a celebrated symbol of the Marines.

"It was the day the U.S. Marines went from being a small force few people knew about to personifying elite status in the US. military," says Andrew Wiest. The corps had roots dating back to the American War of Independence, but from Belleau developed much of the corps' modern lore and myth.

More significantly, and of strategic importance, their intervention at Belleau and that of their 2nd and 3rd Division colleagues in the surrounding area on the Marne put paid to the German advance, at what was a dangerous moment in the war for the Allies.

The commander of the U.S. First Division Robert Lee Bullard subsequently declared: "The Marines didn't win the war here. But they saved the Allies from defeat. Had they arrived a few hours later I think that would have been the beginning of the end. France could not have stood the loss of Paris."

Editor's Note: Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18 (The History Press), American on the Western Front, & on Twitter @AmericanOnTheWF. Inclusion of links does not signify Army or DOD endorsement.

Social Sharing