In May 1864 the War between the States had entered its fourth year. In the Eastern Theater a succession of Union commanders had been unable to achieve decisive results, and the Union Army of the Potomac under Major General George G. Meade was ready to abandon winter quarters around Culpeper, Virginia, to again seek a war-winning victory over a resolute Confederate Army of Northern Virginia led by General Robert E. Lee.

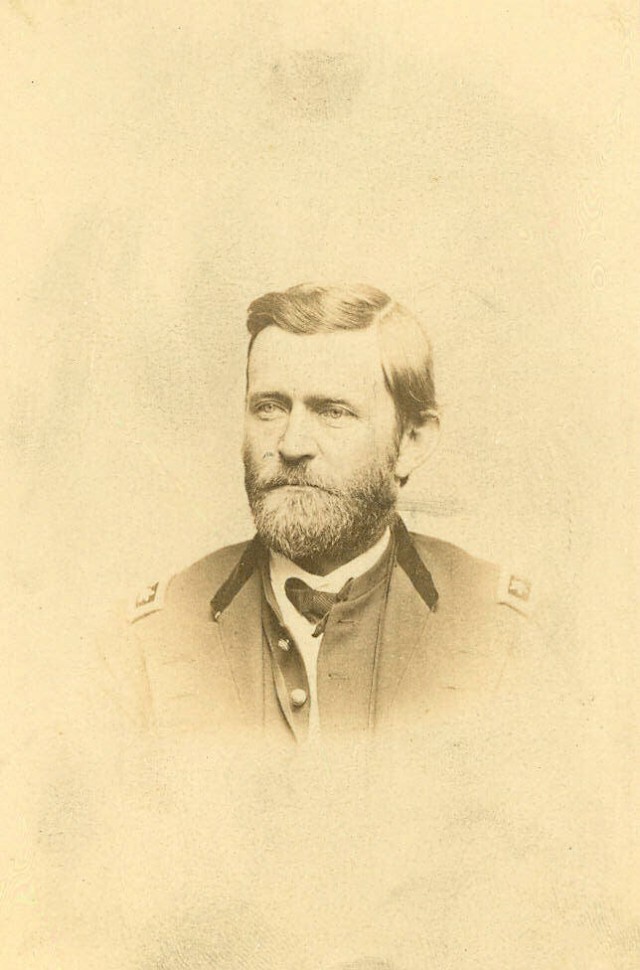

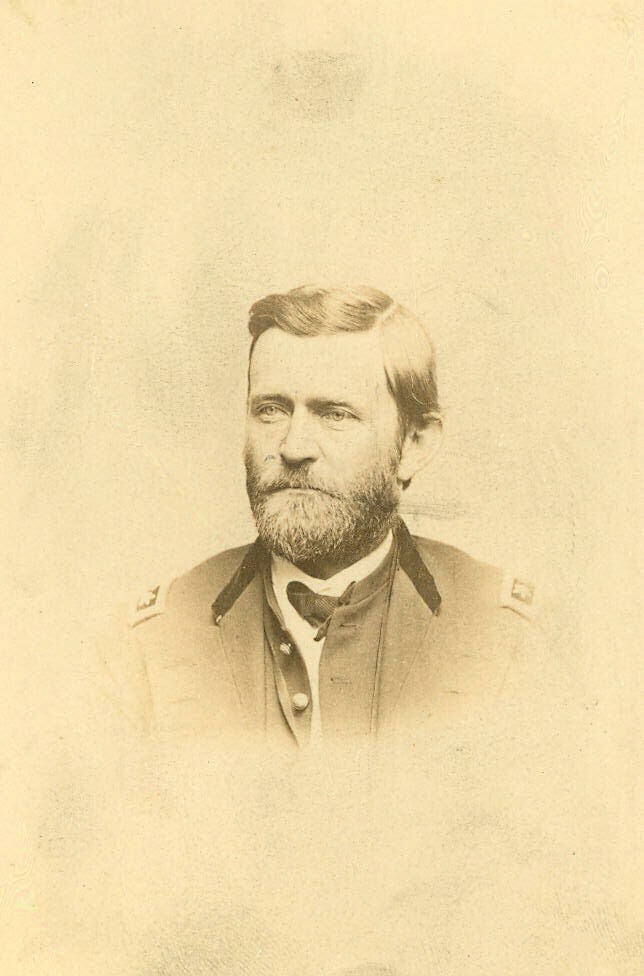

In March of 1864 the most successful serving Union GeneralAca,!"Ulysses S. Grant, hero of Vicksburg and ChattanoogaAca,!"was elevated to Lieutenant General and placed in command of all Union armies.. The only previous officer to hold that grade was George Washington himself, and even he had been raised to Lieutenant General very late in his active public life after his Presidency (during the Naval War of 1798). Winfield Scott, moreover, had been Aca,!A"brevettedAca,!A? [awarded the Aca,!A"honorableAca,!A? right to the rank without an actual promotion] to Lieutenant General only after a long career of Army leadership. Congress was not convinced that the Republic needed a senior general until the winter of 1863-1864, and even then there were some who were unconvinced that Grant was the right man for the job.

U.S. Grant had graduated from the Military Academy at West Point, served with some distinction in the War with Mexico, but resigned his commission in 1854. He was unsuccessful at everything he tried as a civilian, so when war broke out in 1861 he volunteered for service in Illinois, where he was soon made colonel of a Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He rose quickly in the expanding Union Army, gaining prominence by demandingAca,!"and receivingAca,!"the Aca,!A"Unconditional SurrenderAca,!A? of Confederate forces at Fort Donelson in February 1862. Other victories followed, but Grant was rumored to be a drunkard, dressed for comfort rather than show, and had tempestuous relations with military correspondentsAca,!"hardly the formula for becoming an acclaimed savior of the Republic.

In the spring of 1864 Lieutenant General Grant set out to put all of the Union Armies on the offensive simultaneously. As he wrote to MG Meade in early April 1864, Aca,!A"So far as practicable all the armies are to move together, and towards one common center. Banks has been instructed . . . to concentrate all the forces he can, not less than 25,000 men, to move on Mobile. . . . Sherman will move at the same time you do, or two or three days in advance, JohnstonAca,!a,,cs army being his objective point, and the heart of Georgia his ultimate aim. . . . Sigel cannot spare troops from his army to reinforce either of the great armies, but he can aid them by moving directly to his front [up the Shenandoah Valley]. . . .Butler can reduce his garrison so as to take 23,000 men into the field to his front. . . . Butler will seize City Point and operate against Richmond from the south side of the [James] river. His movement will be simultaneous with yours. LeeAca,!a,,cs army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.Aca,!A?

The operations were not perfectly synchronized, but the major elements assumed the offensive in early May. The Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River on May 4 and advanced into the Wilderness before General Lee could block them.. But LeeAca,!a,,cs reaction was sharp and carried bloody consequences for both armies. Two Confederate corps marched quickly to stop Union advances before they could clear the confines of the Wilderness (where Union superiority in artillery and manpower was largely neutralized). Heavy fighting raged throughout May 5-6, with LeeAca,!a,,cs third corps arriving on the morning of May 6 to offset potential Union advantages. Lee fought Meade to a stalemate.

In earlier campaigns Union forces had retreated across the river at that stage, but Grant ordered the pontoon bridges taken up and notified Meade to prepare for a march deeper into Virginia. Even though the Army of the Potomac had sustained about 18,000 casualties (killed, wounded, and missing) in two horrible days in the Wilderness, Union Soldiers cheered Grant when they discovered that they would continue to march south. They finally had a general who would continue to push until they achieved final victory.

Major General William T. ShermanAca,!a,,cs armies set off on their famous fighting march for Atlanta at virtually the same time that Meade fought in the Wilderness. The other armies were not as successful as Grant had hoped, but Confederate commanders were deprived of flexibility as they faced offensives on multiple fronts. Much hard fighting remained, but the offensives Lieutenant General Grant launched in early May 1864 were the first steps toward the ultimate Union victory in April 1865.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the: Army Heritage and Education Center (AHEC), 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021.

Social Sharing