FORT LEONARD WOOD, Mo. -- "Fire in the hole! Fire in the hole! Fire in the hole!"

Under the blanket of darkness, a small fire team of young lieutenants detonated their last breaching charge, sending wooden-door shards in multiple directions. The explosion radiated through the small simulated city hidden in the wooded areas of Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

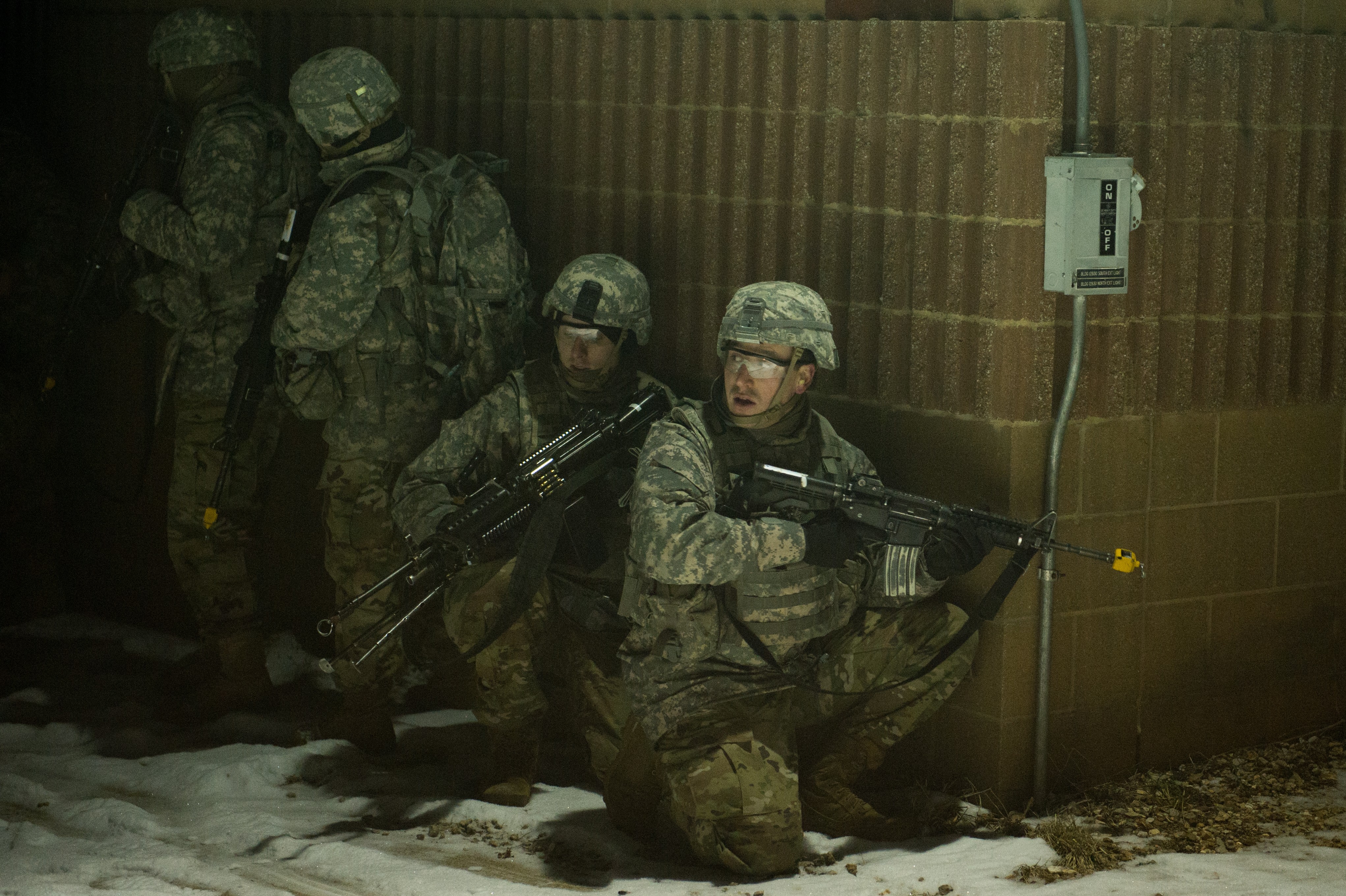

As teams move into the buildings, all hell breaks loose. Both friendly and opposing forces start to open fire, sending groups of young lieutenants in multiple directions. In between the sound of blanks firing, squad leaders bark orders to their unit to try to take control of the situation.

As officers from the Engineer Basic Officer Leaders Course moved into the center of the city, squads of lieutenants collapsed down onto a building with known enemy activity. The young officers moved through the building, clearing room after room, but taking many casualties along the way. It took several squads to clear the objective, but eventually, all the enemy forces were killed or apprehended.

As the sun began to rise, cresting over the tree line, an "end exercise" was announced. EBOLC students flooded into a small holding area to complete their after-action reports and provide accountability. During that time, training cadre went through the entire exercise, filling in the gaps with information provided from each squad leader.

Near the end, the cadre reinforced the importance of excellent communication and decisive leadership.

"These exercises prepare the officers to execute mobility operations, by eliminating obstacles and taking out enemy forces," said Capt. David Glisson, an EBOLC cadre with the 554th Engineer Battalion. "This is something that is very realistic that they're going to practice as a platoon leader with their platoons."

ENGINEER BASIC OFFICER LEADERS COURSE

An engineer is a person who applies mobility, counter-mobility, survivability, geospatial, and general engineering skills on a battlefield so that all can accomplish the mission, said Col. Martin D. Snider, commander of the 1st Engineer Brigade.

Engineering officers, or 12As, are responsible for providing a wide range of engineering support to the Army. To qualify as a 12A, each officer must complete the 20-week Engineer Basic Officer Leaders Course at Fort Leonard Wood.

The foundation of EBOLC is built on leadership fundamentals, which includes instruction on Army doctrine and values, and the warrior ethos. During the course, officers also cultivate their core Army tasks of shoot, move, and communicate.

"Everything we do as a class builds on our leadership. It builds on our problem solving," said 2nd Lt. Shannon Kendrick, an EBOLC trainee. "A lot of people are going to be relying on my expertise as an engineer officer. It definitely helps me to think I need to be at the top of my game. I need to learn all that I can and just continue to better myself so that I can help others and save lives."

As training continues, officers move into a block of classroom instruction focused on the various capabilities of Army engineering.

"Officers learn a gamut of different engineer tasks that the engineer branch will go out and complete. This includes plumbing, running water lines or sewer lines, electrical, carpentry, horizontal and vertical construction, and project management, to name a few," said Capt. Jeremiah Paterson, an EBOLC platoon trainer with the 554th Engineer Battalion.

During the last weeks of training, engineering officers move into the field for a series of exercises, which include an urban assault field training exercise, or FTX. Eventually, engineering officers must complete a lengthy overnight march through the backwoods of Fort Leonard Wood -- often referred to as the Sapper Stakes FTX. Upon completion, officers will receive their Army Engineer Regimental Corps crest, solidifying their position as an Army engineer.

"Oh man, when we finally finish Sapper Stakes and cross that finish line and finally get to pin the regimental crest, I'll be very, very proud of everything we've been able to accomplish here," said 2nd Lt. Tory Zollinger, an EBOLC student.

At that time, Zollinger was just days away from finishing his training as an Army engineer.

"A lot of people go through this training every year, but that doesn't take away from the special feeling that you get when you're finally finished," he said. "We finally prove ourselves as branch-qualified engineers, and we're able to go forward to our units and say that we now have a basic understanding of what engineers do. From our units, we'll be able to get a more thorough understanding of what we need to do in order to serve our Soldiers best."

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ARMY ENGINEERING

Army engineers can trace their lineage back to June 16, 1775. Throughout the Revolutionary War, Army engineers -- with ranks filled mostly by Frenchmen -- played a vital role by erecting fortifications from Boston, Massachusetts, to Charleston, North Carolina.

Moreover, Army engineers enabled military movement by mapping terrain, clearing paths and building encampments.

Understanding the potential impact of engineering on the battlefield, Gen. George Washington started up the first engineering school in West Point, New York, in 1778. However, at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, the school was dissolved, and many engineers were forced out of service.

It wasn't until 1801 when the War Department revived the school and put Maj. Jonathan Williams in charge of the "Corps of Artillerists and Engineers."

The following year, President Thomas Jefferson signed legislation that created the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and re-established what is known today as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

During that time, Williams served as the first superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy and as the chief of engineers. He is the only person to hold both titles in the school's history, Snider said.

For the next 64 years, the Corps supervised the Academy's daily operations. Although the curriculum was heavily laced with engineering subjects, the Academy still worked to commission officers into all branches of service. Supervision of the Academy was passed to the War Department following the Civil War in 1866.

As the role of the Academy evolved, separating itself from its engineering roots, leaders still identified a need for an independent engineering school.

From 1868 to 1885, an informal "School of Application" was established in Willets Point, New York -- now known as Fort Totten. In 1885, the school was formally recognized by the War Department. By 1890, it had changed into the United States Engineer School.

Moving into the 20th century, the engineering school underwent a lot of changes. In 1901, the school moved from Willets Point to Washington Barracks in Washington D.C. During World War I, instructors and students at the school were needed to man an expanding engineer force, which forced a closure of the school.

In 1920, the school resumed instruction, but was moved to Fort Belvoir, Virginia. For the next 68 years, Belvoir served as the premier training location for thousands of officer and enlisted engineers. Many of them saw action during World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam. In 1988, the Engineer School moved to Fort Leonard Wood, where it has remained to this day.

As an engineer in training, Zollinger said he was surprised to learn of the history of his branch.

"I found it fascinating that the engineers have existed as long as the Army has existed," Zollinger said. "It's an older branch than all the other branches. Minus maybe infantry and field artillery. I just found it so fascinating the role that engineers have played and how most people don't know much about the engineers."

For the past 243 years, Army engineers have played a vital role in the development and shaping of the nation and other parts of the world, said Brig. Gen. Robert Whittle, Engineer School commandant.

"There are just countless examples of what we're able to do," Whittle said. "The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for everything -- from making sure our waterways are navigable, to environmental cleanups across the country. Additionally, combat engineers come up with their solutions. They can build bridges to help maneuver forces, cross rivers, or if we're needed on the defense, they can destroy bridges to help protect friendly forces."

TWO PATHS, ONE MISSION

Upon graduation, officers support either the general or combat engineering disciplines.

General engineering is the largest percentage of engineer support that is provided to an operation. It occurs throughout the areas of operation, at all levels of war, and during every type of military operation.

Some of those responsibilities for general engineering include supporting the construction of structures and base camps, repairing and restoring military and civilian infrastructure, and developing civil works programs.

"Our general engineering capability is one in the future that we will use the most," Whittle said. "We have plumbers, carpenters, and electricians, all kinds of different military occupational specialties."

A portion of the nation's general engineering support comes from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. USACE has approximately 37,000 dedicated civilians and Soldiers delivering engineering services to customers in more than 130 countries worldwide. The Corps bolsters the nation's security by building and maintaining America's infrastructure and providing military facilities so that service members can live, train, and work.

COMBAT ENGINEERING OFFICERS

In contrast to general engineering, combat engineers, also known as "Sappers," learn how to place demolitions, conduct reconnaissance and support maneuver units. Tasks include such things as building bridges and roads, laying or clearing minefields, conducting demolitions, and constructing or repairing airfields.

"[Combat engineers] bring the leadership, guidance, direction, and motivation to complete our mission and the commander's intent," Paterson said. "Overall, 12Bs bring mobility and counter-mobility assets to the maneuver force. We make it so they can move forward or so that the enemy can't move forward on us by clearing ways or blocking roads."

What all engineers do, officer and enlisted, combat and general, is solve problems. And that's appealing to those who choose to serve the Army as engineers.

"My favorite part of engineering, bar none, is the solving of hard problems. Problem-solving requires mental flexibility," Snider said. "Who has the skill sets and the equipment and the training to solve a problem? Engineer's do."

(Editor's note: In support of Army Engineer Week, this is the first of a four-part series about Army engineers and their profession.)

Related Links:

Engineers serve as diverse enablers in Army

Social Sharing