NATICK, Mass. -- The Meal Ready to Eat, or MRE, the same individual field ration designed to sustain the health and energy of America's warriors on the battlefield, can also be used to nourish babies suffering dehydration in disaster zones.

That's what the U.S. Army's Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center's Combat Feeding Directorate, where food technologists first developed the MRE in 1982 and have continued to improve it since, recently learned after hearing a remarkable story about a unique application of the Army's most versatile field ration.

During a visit to NSRDEC for the Army birthday in June 2017, one of the invited guests, a captain in the Town of Natick's Fire Department, was sampling CFD's latest ration developments when he casually mentioned seeing emergency medical workers use MRE components to treat dehydrated babies in Haiti during the humanitarian response to a 2010 earthquake.

The captain's story amazed everyone in the room, particularly members of CFD, who were hearing for the first time about the critical role MREs played in saving young lives more than seven years ago.

"It was an interesting story," said Eryn Flynn, CFD's lead outreach coordinator, who facilitated the Army birthday ration samplings for distinguished visitors. "It was surprising to learn about MRE components being used as an emergency rehydration solution for babies in Haiti seven years after it happened."

EMERGENCY MEDICAL DISASTER RESPONSE

When a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the tiny, impoverished island-nation of Haiti in January 2010, causing hundreds of thousands of deaths, injuries and millions of displaced victims, aid workers from around the world faced an epic humanitarian crisis.

Within 72 hours of the catastrophic event, the Massachusetts -- 1 Disaster Medical Assistance Team, or MA-1 DMAT, out of Boston, deployed to the capital city of Port-au-Prince in support of the international disaster relief efforts.

As the MA-1 DMAT lead pharmacist, Dr. Shannon Manzi was one of the first responders on the ground providing desperately needed medical attention to the injured and sick, including moderately and severely dehydrated babies.

"In January of 2010, we saw, like everybody else watching the news, that there was a massive earthquake in Haiti," said Manzi. "When we are on call, if anything happens I have three hours to get to the airport. So my bag is always packed and ready to go."

Manzi, whose full-time job is as director of the Clinical Pharmacogenomics Service and manager for the Emergency Department and Intensive Care Units Pharmacy Services at Boston Children's Hospital, has also been on the MA-1 DMAT disaster team since 2001, deploying to both domestic and international disaster areas to provide emergency medical services to victims of hurricanes, earthquakes and other humanitarian crises such as the unaccompanied minor border crossings in Nogales, Arizona in 2014.

"I've responded to every hurricane named where federal assets were deployed, short of Andrew in 1992 -- because I wasn't on the team yet. Additionally outside of DMAT, I have been on medical missions in Malawi" said Manzi.

When deployed, Manzi and her team are covered under the Uniformed Service Employment and Reemployment Rights Act, or USERRA, a federal law that establishes rights and responsibilities for uniformed service members and their civilian employers, which protects civilian job rights and benefits for veterans and members of the active and Reserve components of the U.S. armed forces.

Most recently, Manzi deployed with MA-1 DMAT to Hurricane Irma disaster zones, and is expecting to go to Puerto Rico in a few weeks.

"We're similar to the public health service in some ways, notably different in that we are intermittent federal employees with civilian full time jobs in our discipline. Our role is also significantly different from global health missions because we go into an area where there generally is a complete lack of infrastructure," said Manzi.

According to Manzi, MA-1 DMAT is one of 54 active disaster response teams right now in the U.S., with an average roster of about 100 healthcare providers from all different disciplines, including physicians, nurses, medics, pharmacists, respiratory therapists and behavioral health practitioners.

After being staged first at the airport and then the U.S. Embassy, Manzi's team finally reached the area that would become their field station.

"There were some NGO [non-government organizations] providers already there, but from an official U.S. government response, we were the first U.S. boots on the ground," said Manzi. "We ended up in a courtyard area within some buildings of an old medical school that the U.S. had built in the [19]60s and then abandoned for a new school that was built, but unfortunately, (it was) heavily damaged during the earthquake.

"But the courtyard was available and right next to the multitude of tent cities that were built, so we set up the whole works within that courtyard, with an operating room, patient care area, pharmacy, logistics, and billeting area for the staff."

Once on the ground, Manzi and MA-1 DMAT needed to link up with their command and control unit, called the Incident Response Coordination Team, or IRCT, to establish what their mission was going to be.

The IRCT's job is to find the missions and match them to each emergency medical response team based upon the needs, which were identified as "untreated wounds, ongoing medical care, and a huge concern for infectious disease, especially as conditions became more unsanitary," said Manzi. "As you can imagine, there's a lot of chaos that happens early on, and the goal is to have great communication to know what the needs are, but that's hard when there's no infrastructure to start with.

"Our mission was to establish a field hospital and take care of anyone that came to us. A secondary mission was to offload some of the general hospital because they were damaged, as well. They had patients on the lawn. They were overwhelmed and simply could not take any more patients."

Manzi's team treated a variety of patients and injuries.

"It really depends on the disaster," Manzi said. "We could have something as simple as a laceration, which doesn't require a lot of care, to something as complicated as an amputation, which we've had to do. And of course, all other types of medical patients. With Haiti, it was a lot of crush injuries, some burns, but mostly crush injuries.

"We treated everyone from hours old newborns to adults for wound care, to surgery; other patients had some brief interventions that had been done by someone else on the scene that we checked for infection, cleaned and bandaged back up, fevers, babies and adolescents for tetanus shots.

"You name it, we had it, and so it was a whole medical to surgical contingent.

"And then you get the pregnant women who are going to deliver no matter what; regardless of what Mother Nature does, it's going to happen. Our very first patient was an expecting mother who was about to deliver."

A SOLUTION BECOMES THE SOLUTION

"When you get shipped to Haiti with a whole bunch of insulin, and there's not a diabetic to be found and only six bottles of electrolyte replacement solution, you've got a problem," said Manzi. "As we went on with treating patients, we had a number of dehydrated pediatric patients; in fact, the vast majority of our patients were pediatric -- orthopedic and pediatric -- along with people who just didn't have enough to drink or eat.

"Then you get more diarrhea illnesses as the disaster goes on because you have compromised infrastructure, and their infrastructure was not all that robust to begin with."

According to the World Health Organization, or WHO, diarrheal disease, resulting in dehydration caused by contaminated food and water sources, is a leading cause of child mortality and morbidity in the world.

The WHO reports that during a diarrheal episode, water and electrolytes (sodium, chloride, potassium and bicarbonate) are lost through liquid stools, vomit, sweat, urine and breathing. Dehydration occurs when these losses are not replaced and is a life-threatening risk to infants and young children, especially when they are victims of natural disasters in developing countries.

"So we were really quickly running out of our electrolyte replacement solution that we brought with us," Manzi said. "There is a small amount in our basic load, which includes our pharmacy cache but it was never set up for this type of mission per se, so we ran out.

"Resupply at that point was a challenge. The airport was very severely damaged, and there were tons of flights trying to get in and out from all over the world, bringing supplies and relief workers in, trying to get people out of Haiti, so the airstrip time was extremely limited and getting supplies into the country was very challenging, to say the least. Basically, we knew a resupply wasn't going to happen anytime soon."

So when emergency medical workers ran out of the commercially made electrolyte solution they brought with them, Manzi had to improvise an alternative. She came up with an innovative solution.

"My supervisor asked me our status on rehydration solution, and I told him, 'It's bad; we only have two bottles left.' He asked, 'So what's your plan?'"

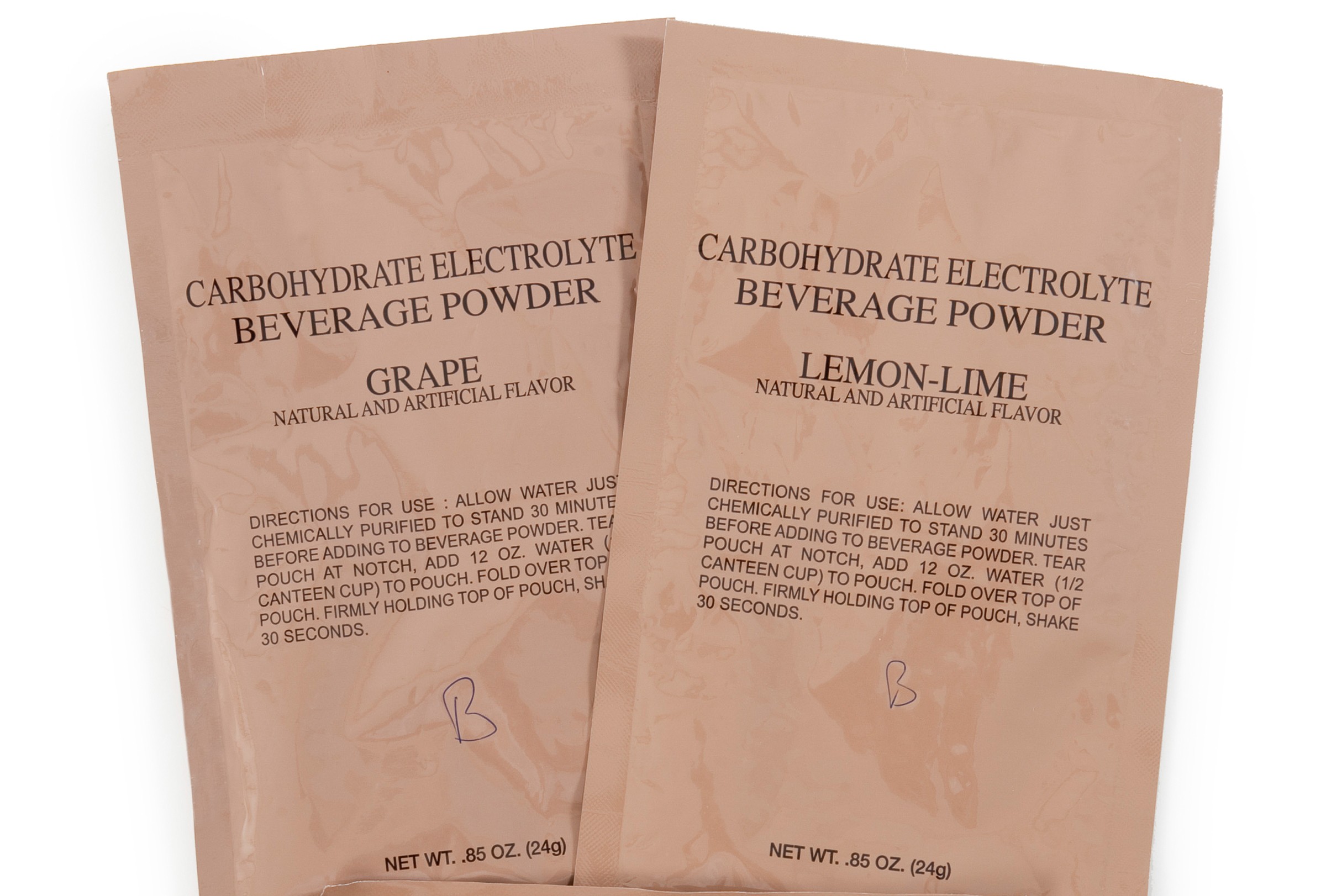

"I said, 'Well, honestly, I can make it. We're going to have to make our own bottles of solution because most of our patients are pediatric patients. I just need everybody to start dropping off their sugar and salt packets, and if they're willing to part with their drink flavorings, like fruit punch, etc., from their MREs for their water bottles."

The staff was more than willing to help out.

"I put a box out that said, 'Please donate to the kids. I need salt, sugar and flavoring packets,' and everyone had to pass the pharmacy to pick up their MREs, anyway, because of our location and where we were in relation to the MREs. And every day I'd have enough needed to make the WHO recipe.

"We had the 82nd Airborne Division there as our force protection, and even they were donating those components from their MREs. So it was more of a morale booster than anything else.

"It became more about buoying the feeling of people who were there helping. People would say to me, 'Hey, I'm going to go without sugar in my coffee today and give it to you for the babies.'

"So that's what we did. I had previously downloaded the recipe from the WHO website and was ready to go."

WHO's preferred low osmolarity oral rehydration solution calls for:

Full strength (to be used by those who can drink and are not clinically dehydrated):

75 mEq/L sodium

70 mmol/L glucose*

*glucose is preferred over sucrose, but home recipes allow for use of sucrose

Half strength for oral or NG rehydration:

25 grams glucose (equivalent to 10 level teaspoons)

37.5 mEq sodium (equivalent to ~1/3 tsp table salt)

40 mmol potassium (equivalent to 40 mEq potassium)

1 liter clean water

Final concentrations: 37.5 mEq/L sodium, 40 mmol/L potassium, 25 grams/L glucose

"We were able to use some of our intravenous potassium, which we weren't using otherwise at that time, unless they were going into the surgical suite," Manzi said. "So I was able to use the salt out of the MREs, the sugar out of the MREs, and the flavoring packet out of the MREs, and the potassium out of the intravenous solution, and make the WHO preferred oral rehydration solution, both full strength and half strength.

"I would mix the sucrose (sugar) with the sodium chloride (salt), take a look at it, then add the potassium I had available and obviously clean drinking water, bottle it up, label it. Sometimes I had flavoring to add to it, and sometimes I didn't. When I had the flavoring, it was definitely more appealing to the children.

"And for some kids, this was secondary for what they came in for. If they had an infection but were also severely dehydrated, we'd also treat them for that.

"We had some oral syringes with us for the very tiny babies and little ones. The big kids just drank it out of cups or whatever we had available. And for the kids that were too sick to drink it, we had to drop an NG [nasal gastric] tube, which you don't want to do if you can get the patient to drink it.

"It's a more appropriate rehydration solution to rebalance the electrolytes, especially when there's vomiting, diarrhea or just the inability to find clean drinking water. Over time, your electrolytes become completely unbalanced so there were some derangements that we had to fix, and those can be so severe that it causes seizures, muscles spasms and pain.

"I just kept making it because we didn't get resupplied during our deployment -- at least five or six batches of that myself, and then taught the other pharmacist how to make it. I did the day shifts, and she did the night shifts.

"I ended up handing it over to the next team, who relieved us after a few weeks."

MRE BOXES BECOME INFANT INCUBATORS

Emergency medical workers also found novel ways to use different parts of the MRE packaging and cases they come in, something familiar to Soldiers.

"We also used the MRE boxes as cribs," Manzi said. "MRE boxes were a very coveted item because you can use them for anything. We had one on top of a stretcher and had to make basically an incubator for the newborn babies whom we needed to keep warm. So we put the space blanket in it and the other blankets inside that. Then we'd put a sign on it that said, 'Baby in a Box, Don't Throw Away.'"

Manzi's husband, also a member of MA-1 DMAT whom she met during Hurricane Katrina, uses the MRE bags' outer packaging for their waterproof properties.

"He attached Velcro to them to make his own waterproof packs," Manzi said. "When I deploy, I bring a lot of references with me, and when you're in the field, you have to be innovative when you're in an austere environment."

"We've known for quite some time that the MRE and its packaging has utility beyond just food," said CFD's deputy director Jeremy Whitsitt. "Soldiers and Marines are very innovative in finding creative uses for almost everything in the ration, but the way in which it was used in Haiti, as described by Dr. Manzi, is truly amazing."

"We're happy to have played a role in helping so many wounded, hurting, and displaced people."

---

The U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center is part of the U.S. Army Research, Development and Engineering Command, which has the mission to provide innovative research, development and engineering to produce capabilities for decisive overmatch to the Army against the complexities of the current and future operating environments in support of the Joint Warfighter and the Nation. RDECOM is a major subordinate command of the U.S. Army Materiel Command.

Social Sharing