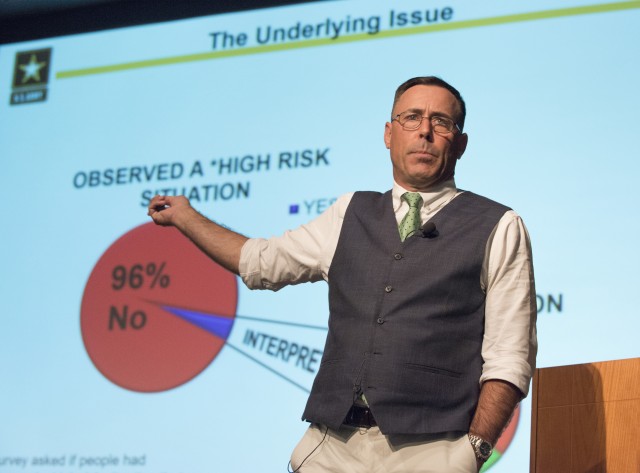

ALEXANDRIA, Va. -- The underlying issue facing the Army's Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention program is not that Soldiers don't intervene when an incident occurs. It's that Soldiers don't always recognize a potential problem to begin with.

Master Sgt. Jeff Fenlason made that point as he introduced SHARP professionals to "Mind's Eye II," a grassroots leadership development program he helped create while at 3rd Infantry Division. The course is currently being considered to be taught at units around the Army.

In fiscal year 2016, Soldiers reported nearly 2,500 incidents of sexual assault. Soldiers have learned what sexual assault is, that the Army doesn't approve of sexual assault, and that they should intervene when they are witnessing the precursors to a sexual assault.

Fenlason said he believes the next step in reducing sexual assaults involves getting Soldiers to interpret high-risk situations that can lead to incidents that may otherwise go unreported.

"We don't have an intervention problem, we have a recognition problem," he said, speaking Thursday at the third annual SHARP Program Improvement Forum. "What we need to do is help Soldiers see."

After senior leaders ordered a stand-down to curb Army sexual assaults in 2012, Fenlason and others at the 3rd Infantry Division's 1st Brigade looked at how to prevent sexual assault within their unit and developed the course.

The interactive, scenario-based Mind's Eye course garnered interest from other units. Fenlason soon traveled to other installations to train Soldiers on the course. His work sparked interest with Army leadership.

"It truly was a unique opportunity to take Big Army concepts and bring them down to a brigade level," he said, "and then put them in the hands of Soldiers who could deliver them capably inside the formation to make that brigade better."

Intended to be a 5 1/2-hour training course that builds trust among unit members, the program -- now called Mind's Eye II -- is slated for a pilot program in January to decide whether it should be pushed out to the entire force.

The course is ideally taught to a group of 15-25 Soldiers by an "influencer" -- a person who unit members tend to gravitate toward. Influencers are selected by their leadership regardless of rank or position, and they are tasked with helping change a unit's culture to one that values respect for each other.

"This is something that we could potentially put in our formations and get folks to think differently," said Monique Ferrell, director of the SHARP program. "I'm really excited about it."

PILOT PLANS

Two U.S. Army Forces Command brigades, which were not identified, are expected to participate in the pilot. While one brigade will actively take part in the course, the other is a control group and will not.

Iterative surveys by Soldiers throughout the pilot will then gauge the effectiveness of the course before any decisions are made to roll it out.

"Too often we put things out into the field [and] we don't know whether they work or not and we never take them out," Ferrell said. "So, we're being very deliberate about this."

In his experience, Fenlason said, the course typically generates meaningful conversations among Soldiers who can share their own opinions and judgments of the world.

"Soldiers enjoy it because they're involved from the very beginning," he said. "It asks you to reflect on your sense of self and your Army identity. It's very much grounded in the adult learning model of stories and recollections and reframing thought processes based on previous experience.

"They're not told the answer. They're allowed to discover the answer."

SELF-REFLECTION

The Army presently has the Not in My Squad initiative, which gives junior leaders more responsibility to rid their ranks of negative behavior. While similar, the Mind's Eye program has a more inward approach in bringing more professionalism to a unit.

"Not in My Squad makes you look outward at your formation," Fenlason said, quoting a Soldier he had met with who had trained on both Mind's Eye and Not in My Squad. "Mind's Eye II forces you to look inward at your [own] leadership. Together, they are a powerful combination."

In Mind's Eye, different scenarios are presented to Soldiers who realize there may be several answers to what might be an ambiguous problem. A Soldier's answer has much to do with who they are as a person and the sense of their place in the unit they serve in.

"So, what does it mean to be a member of this team?" he asked. "In this team, we have expectations that people will intervene, take care of each other, look out for each other.

"Everyone wants to be a member of the team," he added. "All we're asking is who's defining what that membership looks like."

High-risk situations where a sexual assault can take place, he said, can also go unnoticed due to societal norms. "We live in a culture that says mind your own business," he said.

Campaigns against drunken driving, for example, helped change how people thought about it and made them more aware of its negative impact. "First, you have to recognize that it is a mistake," he said.

In the same way, sexual assaults can rely on that failure to speak up.

"All crises orbit around silence," Fenlason said. "You don't have a crisis if we're talking about it. I don't care how bad it is. Silence by a third party equals agreement on the existing condition."

After hearing the presentation for the first time, Meghan McAndrew, lead sexual assault response coordinator for the Joint Munitions Command, agreed and said she has noticed that type of silent behavior across society.

"If you're not looking around and trying to mind your own business, how do you recognize?" she asked. "Training like this would really assist us to open our mind and realize that we do need to change our minds in order to be able to recognize and further eliminate sexual harassment and sexual assault, not just within the military, but everywhere."

Social Sharing