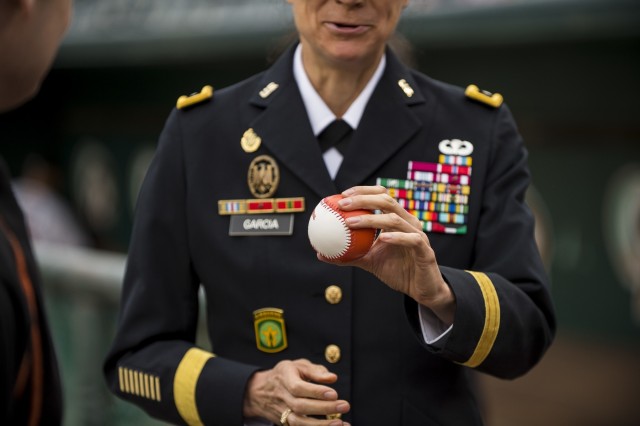

FORT MEADE, Md. - When she pinned on her second star, Maj. Gen. Marion Garcia made no fanfare about it. She kept the ceremony small and private, held at the Pentagon.

"I've been told that I don't act like a general officer. I don't even know what that means. I want to act like the rest of my Soldiers. If not, then how are any of you going to follow me?" she said.

Just the day before pinning her second star at the Pentagon, she was outside in the parking lot of her headquarters training on an Army radio. A small group of Soldiers was training on warrior tasks in preparation for the Best Warrior Competition, and she decided to join them. She laughed when she saw her staff looking out the window at her, bewildered.

Why was their commanding general in the parking lot training on a Single Channel Ground and Airborne Radio System (SINCGARS)?

"We all got to be doing this stuff. I think it's more important for Soldiers to see me work a SINCGARS than watch me get promoted, because holding a parade somewhere isn't going to save my life, nor anyone else's," she said.

Becoming a two-star general is a huge accomplishment in the Army, and yet, for Garcia, rank was never a motivating factor.

"I came off of active duty as a company commander. And it never entered my consciousness that someday I would get promoted to become a general officer. It didn't hit me. It wasn't like I want to be promoted to that rank, or promoted to that rank. It was always: I want to command that! And as it happens, as you command units, you get promoted," said Garcia.

She said this so matter-of-factly, as though earning two stars on her chest made her no different than someone wearing mosquito wings on theirs. When officers first make the rank of general, they receive their own flag, a pistol, a belt and they literally change the pants they wear in their dress uniform. Commanding generals receive a personal aide to manage their schedule, a driver to take them places, and a large staff of officers and sergeants major to crunch huge quantities of information to help them make tough decisions.

Now Garcia has not only one star, but two. She's the commanding general of the 200th Military Police Command, within the U.S. Army Reserve, located at Fort Meade, Maryland. In her role, she's responsible for 14,000 Soldiers - most of which are military police - spread among four brigades, three criminal investigation battalions, with units located across 36 states. Their missions focus on detainee operations, combat support, criminal investigation and overseas law enforcement.

All of this, and she never expected anyone to buy her a cake for her promotion.

Her staff surprised her with a cake anyway, but they joked they might get fired for "making too much of a big deal about her."

When she travels the country to visit Soldiers, if a photographer shows up, she waves him away and tells him to go photograph someone more important: her Soldiers.

During one of these visits to her troops, she was being escorted around when at one point she needed to use the latrine. Her escort tried to stop her.

"No, no, Ma'am," he said. "The VIP latrines are over here."

In her mind, that idea was ridiculous.

"VIP Latrine? Are you somehow telling me that these latrines are inferior? You just gave me a reason to go look at them," she thought.

"You have to keep in mind that I'm a Desert Storm Veteran. Sometimes we didn't even have latrines. I'm a Soldier, and I think I should act like a Soldier," she said.

But in spite of her humility about rank, nobody would ever accuse Garcia of being soft. When she first took over the command, she sent out an email to all her staff and brigade commanders expecting them to read "A Message to Garcia," an essay written by Elbert Hubbard in 1889. Coincidentally, the Garcia in the essay is also a general, but one who fought during the Spanish-American War. If the essay could be summarized into a single message it would be this: "Act with initiative, get the mission done, and don't complain or make excuses."

She expects her staff and her brigade commanders to know their stuff, and to think critically about every problem they face and every solution they offer.

In her civilian career, Garcia is a veterinarian doctor who specializes in animal food manufacturing. She approaches problem solving with the analytical mindset of a scientist.

"I often tell people that I'm a scientist, and I say that, one, because it helps them know how to communicate with me. I make decisions objectively, supported by facts. And I need my commanders to know how to talk to me. But I also tell them that because I don't want everyone around me being a bean counter. I used to have this lieutenant colonel on my staff who had the soul of an artist. I tell you, he was an artist. I would not hold a meeting without him present, and sometimes the rest of the staff would hate it. He would always be the one to say something crazy that nobody else was thinking of. I want that. I'm a scientist, but I need others to balance it out," she said.

Garcia expects much of her Soldiers, especially in a time when conflict and war could erupt anywhere in the world. When that time comes, combatant commanders will be calling up Garcia to deploy her MPs. Taking charge of this command drives her, knowing well there will be high expectations and pressure. It was never the rank, but each opportunity to command that has motivated Garcia in her thirty-plus-year career.

"It's certainly not because others can't do it. A lot of people can do what I do. There's a lot of great commanders and generals out there. I'm not better than them. So my drive to command is not because I can do it better than anyone else. I think it's because I'm one of those people who sees a 17-year-old kid with a sharp haircut, acne all over his face, needs to shave only once a week, and I say to myself, 'I want to work with him. I want to help him achieve excellence.' He may not always love how I lead him, but I'm okay with that. So long as we are striving toward that same goal together," she said.

Social Sharing