FORT HUACHUCA, Ariz. -- When Ralph Van Deman established the War Department's intelligence organization shortly after the United States entered World War I, he was faced with the daunting task of building his section from nearly nothing.

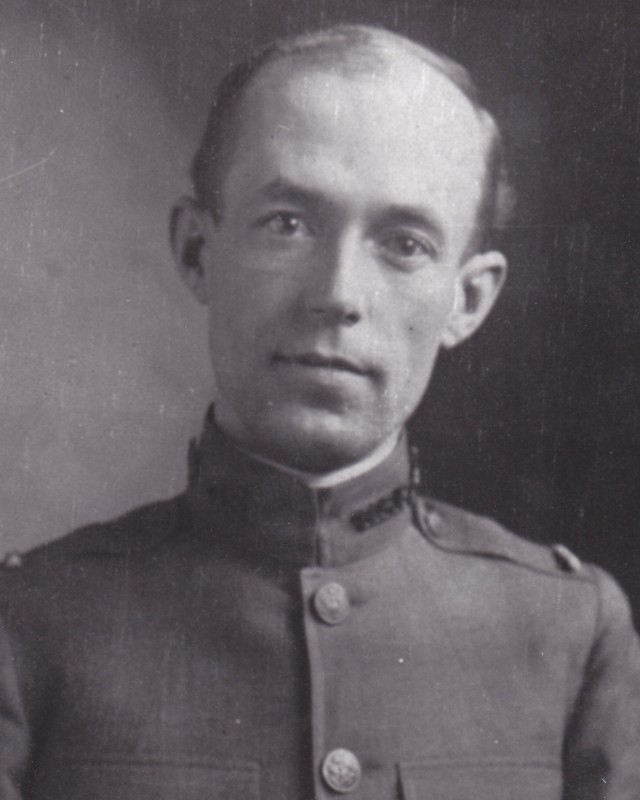

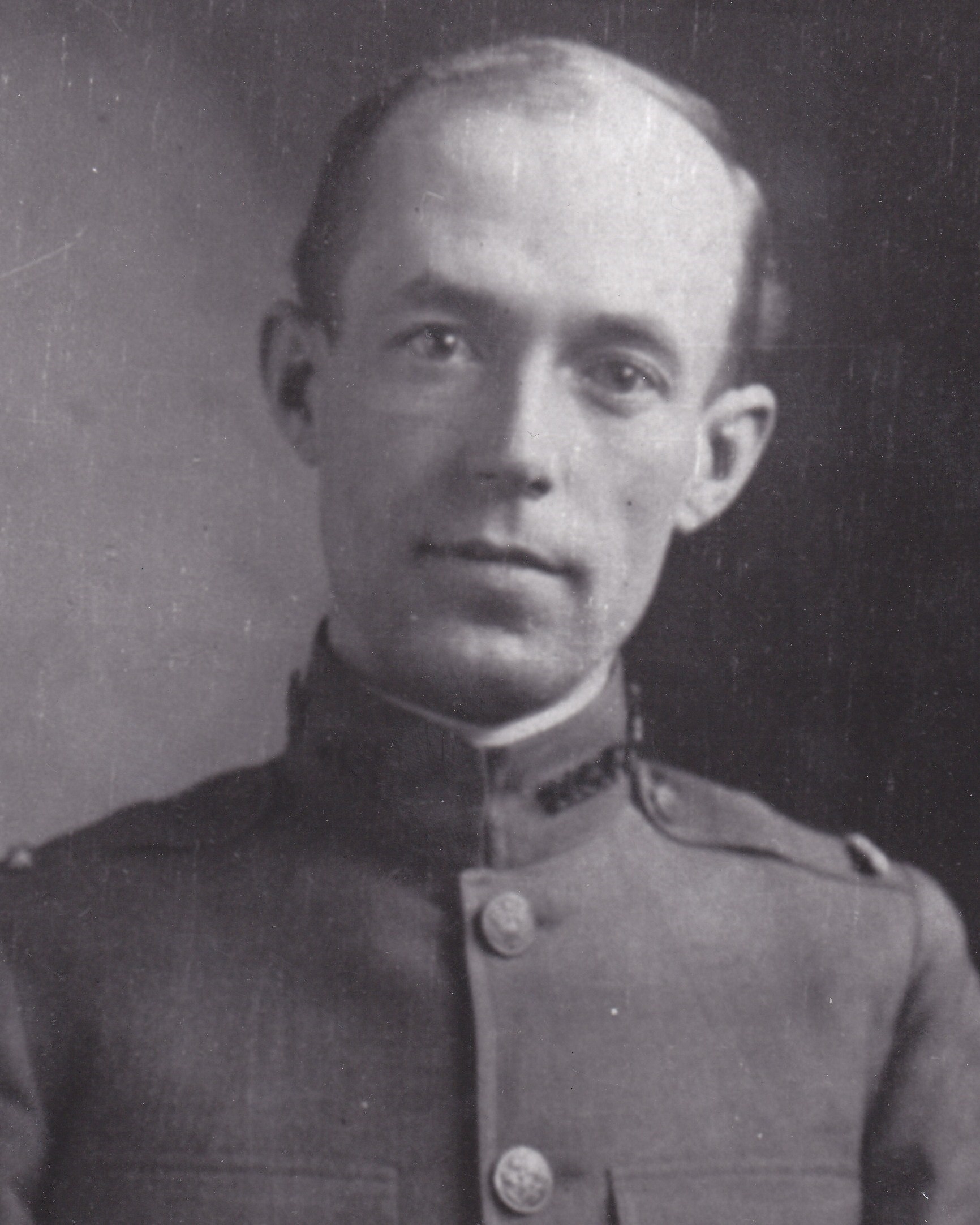

Although his background was more in the field of counterintelligence, he readily recognized the need for an office dedicated to cryptology. He received numerous letters from amateur cryptologists offering their services, but he was intrigued by one person in particular -- a bored State Department telegraph operator named Herbert O. Yardley who had deciphered a communication between President Woodrow Wilson and his aide in two hours.

Putting aside concerns about Yardley's age -- he was only 28 years old -- Van Deman chose him to create the Army's first code and cipher bureau, known originally as the American Cryptographic Bureau but most popularly as MI-8.

Yardley reportedly remarked that "it was immaterial to America whether I or someone else formed such a bureau, but such a bureau must begin to function at once."

Yardley was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Signal Corps on June 29, 1917 and was given two civilian assistants. Over the next year, MI-8 grew rapidly to 165 military and civilian personnel working in five subsections: Code and Cipher Solutions, Code and Cipher Compilation, Secret Inks, Shorthand, and Communications.

Code and Cipher Solutions examined communications from commercial telegraph and cable companies, intercepted radio traffic and seized mail. Every suspicious missive, military or civilian, ended up on the desks of this subsection.

In addition to written communications, the section also analyzed atypical items like postage stamps, musical scores, religious amulets, and even a pigeon's wings. The amount of work was overwhelming, especially after the U.S. Navy stopped its cryptology efforts and let the Army take the lead.

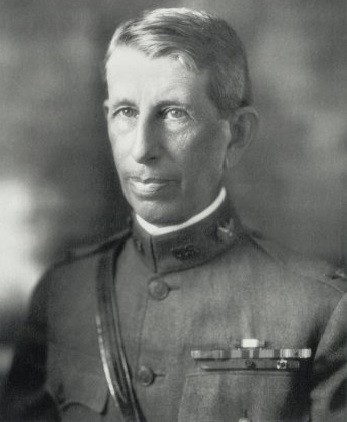

During the course of the war, the subsection read more than 10,000 messages and solved 50 codes and ciphers used by eight foreign nations. This included the celebrated case in which Capt. John Manley deciphered a coded message found on Lothar Witzke (aka Pablo Waberski), a suspected German spy and saboteur. Manley's solution to the code sealed Witzke's conviction for espionage.

The Code and Cipher Compilation Subsection established secure communications for 40-plus military attachés and hundreds of intelligence officers in the American Expeditionary Forces. Its services were critical for several reasons.

First, the Army's 1915 telegraph code book had been stolen during the Punitive Expedition and had yet to be updated. Additionally, British cryptologists informed the War Department that German telegraph operators on U-boats were able to copy U.S. messages sent to the AEF and its allies via the transatlantic cables.

Because breaches in U.S. communications would ultimately compromise the whole Allied effort, the subsection revised the entire War Department code and cipher system. In conjunction, the Communications Subsection operated around the clock, averaging the secure transmission of more than 100 sensitive and classified messages per day.

The Secret Ink Subsection established two laboratories specifically for MI-8 use. Chemists succeeded in developing an iodine vapor reagent for all types of secret inks. As a result, the MI-8 uncovered communications directing sabotage, which allowed the War Industries Board to implement tighter security measures.

At its peak, the subsection was reviewing more than 2,000 items weekly. As more sophisticated methods to conceal messages were developed, the subsection continually worked on new reagents.

The Shorthand Subsection was an impromptu addition to the organization. Military censors provided MI-8 with a number of messages believed to be in code but were found instead to be written in shorthand. The subsection cultivated a community of experts in more than 30 shorthand systems used worldwide.

MI-8's work was at times exciting and often fruitless, but personnel persevered. In a series of post-war articles, Manley stated, "It is the business of a Cipher Bureau never to allow its interests or energies to flag, for although a thousand suspicious documents may turn out…to be entirely innocent or insignificant, the very next one might be of the greatest importance."

Manley also stressed that while the organization successfully uncovered cases of nefarious activities, it also cleared the name of several innocent civilians wrongly accused of spying for Germany.

Although employing relatively simple deciphering methods using little more than pen and paper, MI-8 constituted a significant development for military intelligence during World War I.

Brig. Gen. Marlborough Churchill, the Army's Director of Military Intelligence, predicted in 1919, "Code attack is indeed still in its infancy. It is capable of rapid and incalculable development."

Consequently, both the State and War Departments continued MI-8's efforts as the Black Chamber in the post-war period. Soon thereafter, cryptology evolved into more sophisticated codes and ciphers requiring the invention of mechanical devices that would dominate both Allied and Axis code operations during World War II.

Social Sharing