WASHINGTON -- According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, there are still about 82,540 U.S. service members considered missing in action since World War II began. But that agency doesn't account for the more than 4,400 still missing from World War I.

Thanks to the efforts of several volunteers, the records of these missing WWI men are slowly being unearthed, and more men are identified.

Historian Robert Laplander, known for his research and writings on the "Lost Battalion" of the Great War, started to search for World War I Army Pvt. Eugene Michael McGrath after someone found battle remnants in 2005 at the site of the Lost Battalion's last stand.

"Among the stuff was a dog tag. It was to one of the guys in the Lost Battalion who was missing in action," Laplander said, referring to McGrath. "We decided to see if we could figure out what happened to him."

And thus began the Doughboy MIA Project. Laplander recruited several volunteer researchers, archivists and historians to help search for McGrath's files. Over the years, word got out of their efforts, and they began to look for other fallen World War I service members.

"We have technology today that they didn't have back then: deep-penetration metal detectors, ground penetrating radar, spatial imaging -- all that kind of stuff," Laplander said.

In 2015, Laplander was contacted by someone at the WWI Centennial Commission and asked to highlight their efforts on the centennial's website. Their page, ww1cc.org/MIA, has since grown by leaps and bounds.

THE PROCESS

"Between 1919 and 1932, when searchers went out after the war, the Army made every effort to try to find these men and identify the remains they had recovered that were unknown," Laplander said. "But they had a small team, a lot to do -- the Graves Registration Service handled 80,000 burials after the war -- and they did the whole thing with paper forms and shoeboxes full of index cards."

Since many of those files have disappeared or are located all over the world, it's a long and tedious process.

"It's [often] sitting at a desk looking through boxes. During one case, we went through 200 boxes of burial cards … in four days. We looked at every single card," Laplander said.

Their searches always begin by checking the official list of missing service members to see if they can chronicle their last moves. For those who aren't missing or lost at sea, they first check through 2,300 burial case files, found at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis.

"They can take you in all kinds of directions," Laplander said. "For McGrath, I pulled his [burial] file, and then we decided to pull the file of the guys buried next to him, one on each side, and there was more information in those."

The search for McGrath's final resting place continues (learn more about that journey here at http://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/current-active-cases.html), but the team recently had success in honoring Navy sailor Herbert H. Renshaw.

A TRIBUTE A CENTURY IN THE MAKING

Renshaw joined the Navy in 1914, just after his 17th birthday. The U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, and he was unfortunately a quick casualty. Renshaw was on the USS Ozark, a sub-tender, on its first out-of-harbor mission on May 22, 1917, when he lost his life.

"They hit heavy weather that afternoon. The sea was very rough. He was on the deck of the ship signaling back to another ship, and he was washed overboard," Laplander said.

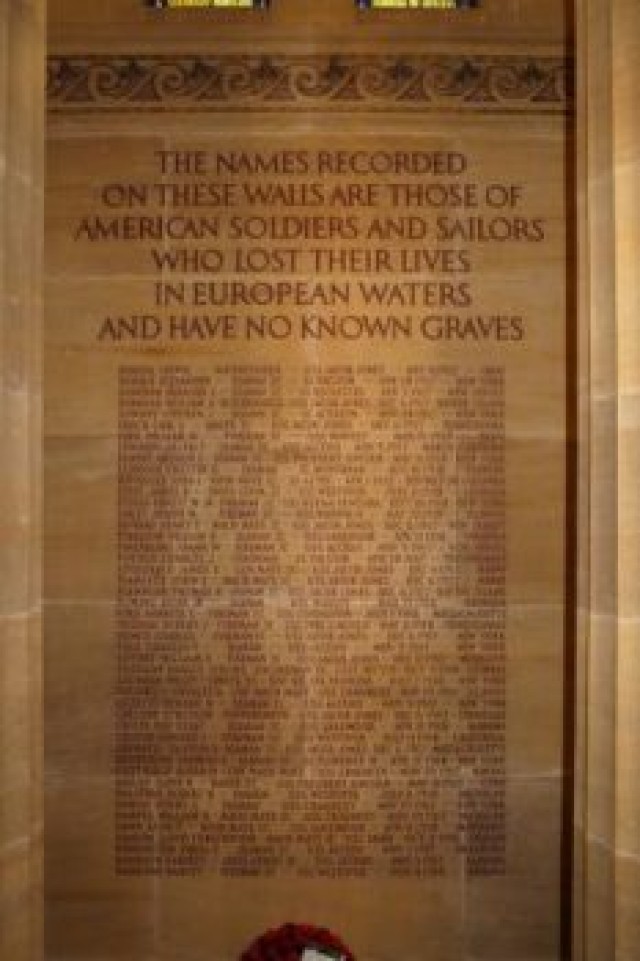

After the war, U.S. lawmakers decided to create American cemeteries overseas, since so many men had died on foreign turf. The names of anyone who was lost at sea, missing or buried in an unmarked grave were carved into walls or tablets at each cemetery.

Renshaw's name should have been added to one of those walls -- but it wasn't, and it took nearly 100 years before anyone noticed. The person who did was Salisbury University professor Dr. Stephen Gehnrich, who was researching Maryland citizens killed in the war. He came across Renshaw's name on a Navy burial file and learned details of his death through old newspaper articles. But Gehnrich noticed Renshaw wasn't on the official list given to the American Battle Monuments Commission, which is in charge of U.S. military cemeteries and memorials. So he contacted Laplander.

Together, the pair did more research and discovered that Renshaw's name had, for whatever reason, been left off the lists provided to the AMBC by the Naval and War Departments.

"In the naval register of sailors and Marines that were lost during WWI, his name is listed. But … his name wasn't engraved at any of our cemeteries," said Tim Nosal, the ABMC's chief of external affairs.

So, the Doughboys petitioned in April to get his named added. Three days later, the ABMC agreed. Renshaw's name would be added at Brookwood American Cemetery in England, where the majority of naval casualties are listed.

"After 100 years, he'll be remembered," Laplander said.

'A MAN IS MISSING ONLY IF HE'S FORGOTTEN'

One question that Laplander always gets: One hundred years later, why do this?

"The answer is the same always -- why not? The first World War was the very first time we sent a major expeditionary force overseas to fight on foreign shores -- not for land, not for wealth, but for an ideal," Laplander said. "If we stand the chance of giving somebody a grave, why wouldn't we?"

His team is working on identifying a few other missing men, including a soldier who had been buried by a chaplain. In a file, they found a description the chaplain gave of the burial area, as well as a set of coordinates he had given officials in 1926.

"Our ground team overseas managed to find the area, and I believe we've found the trench where this guy was buried," Laplander said.

To his team, their tagline, "A man is only missing if he's forgotten," is crucial to their cause.

"Even if we don't recover any more remains or identify anybody else, we've got people thinking about these guys," Laplander said.

Social Sharing