FORT SILL, Okla. -- Many Americans have had pets at one time or another. In fact, about 40 percent of American households have at least one dog. These companions truly become members of the family. They are cherished, pampered, and spared no expense for their medical treatments. They are also mourned terribly when they pass.

Despite the mutual affection between humans and their pets, animals such as dogs and horses have often been viewed more as beasts of burden than as companions, especially in days before the industrialized age. Wartime was no exception. Many of these furred and feathered friends have given their lives in wartime, with the same bravery and dedication as the Soldiers who fought alongside them.

Militaries around the world have honored and awarded their courage and devotion. Movies have even been made about them. "War Horse," for example, was a recent film about a beloved farm horse sold to the British cavalry in World War I.

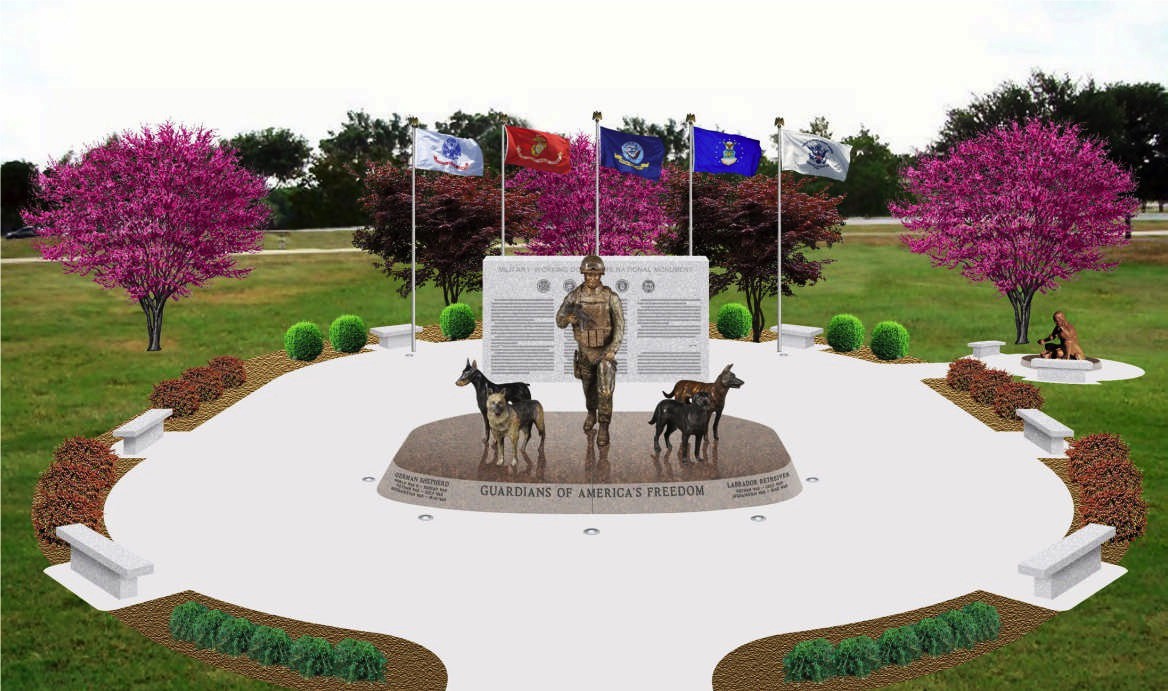

Perhaps the best-known war animals are dogs. More than 30,000 dogs have served in the U.S. military since the K-9 Corps was established by the Army in 1942.

The U.S. military still has around 2,500 active Military Working Dogs (MWDs) today, with 700 or so deployed at any one time. The animals are often tasked with sniffing out explosives and other deadly devices that terrorists might use, and have a 98 percent accuracy.

Tragically, some of these dogs home wounded. Some don't come home at all -- due to death or, previously, to policy.

In fact, it wasn't until recently that K-9s were allowed to return stateside with their Soldier companions.

During the Vietnam War, many MWDs were viewed as surplus equipment, rather than as faithful compatriots who saved lives and boosted the morale of their human counterparts. Following the end of hostilities, these dogs were often euthanized or reluctantly abandoned by the very Soldiers whose lives they saved.

According to a May 2014 article in National Geographic, "This was one of the darkest parts of war dog history." Around 4,000 dogs served in the Vietnam War, and saved around 10,000 lives. The War Dog Association states that only 204 returned home, but not as pets. Many warriors tried unsuccessfully to find out what happened to their canine battle buddies, or to adopt them.

35 years later, a law was passed in 2000 to allow handlers and their families to adopt these faithful soldiers of war.

Problems persisted, however. MWDs that retired overseas were not eligible for military transportation, and so were left behind. In response, the American Humane Society successfully advocated for an additional provision to the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act that ensured military dogs are retired on American soil.

Today, around 90 percent of MWDs are adopted by their former handlers when they retire. Between 2012 and 2014, the Department of Defense adopted out 1,312 dogs to individuals and 252 to law enforcement agencies.

Military dogs have a distinguished record of service throughout U.S. history. They have done everything from carrying messages, laying telegraph wire, detecting mines, digging out bomb victims, and acting as guard or patrol dogs.

Stubby, a bulldog/pitbull/Staffordshire terrier mix, was one such famous MWD. Smuggled to Europe with the American Expeditionary Force during WWI, he became the unofficial mascot of the 102nd Infantry, 26th Yankee Division.

Although he wasn't a trained military dog, he alerted Soldiers to put on their masks when a gas attack occurred. He also captured a German spy dressed as an American Soldier.

Stubby, who was promoted to sergeant, almost died during a gas attack, and he also survived an exploding grenade. After 18 months in war, he returned home. He met three U. S. presidents before he died in 1926.

To honor his service, the government paid for a taxidermy treatment so that Stubby could forever reside in the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Another noteworthy MWD, a Belgian Malinois named Cairo, accompanied the Navy SEAL Team Six when they raided Osama bin Laden's compound.

These elite dogs begin their training at places like the 902nd Military Working Dog Detachment at Fort Sill, Okla. This particular detachment consists of eight dogs trained to sniff for either explosives, or drugs. These MWDs have deployed to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Kuwait; cleared hotel rooms for the secretary of state; and patrolled the convention halls for the 2016 Republican and Democratic National conventions. One team was even specially requested to provide security for the 2017 presidential inauguration in Washington, D.C.

For all of this vital work, the dogs love nothing more than to chew on a kong as a reward, or receive affection and friendship from their human compatriots. When these dogs retire, they are often given a ceremony to honor their service, in addition to a forever home with a loving family.

Social Sharing