FORT BRAGG, N.C. -- It's 3 a.m. and a physician assistant (PA) deployed to a remote location in Africa is sound asleep. All is quiet until an urgent radio call from a Special Forces medic out in the field breaks the silence. A Special Forces Soldier was wounded while conducting clearing operations in a nearby village, and a few of his comrades are transporting him to the PA's location.

The gunshot wound is near the groin and has damaged the femoral artery. It's an injury that can be deadly if care isn't rendered quickly. The unit's medic was able to slow the bleeding by applying a junctional tourniquet, but the measure wasn't able to completely stop the bleeding and now surgical intervention is required.

The physician assistant quickly informs his team that they have a wounded Soldier inbound. As the team prepares the room for the procedure, the PA grabs a pair of augmented reality glasses and starts reviewing the procedure he is about to perform. He then contacts the on-call trauma surgeon, who is stateside and more than 3,000 miles away. Though they are physically separated, the surgeon will be able to monitor and communicate with the PA through the communications link created by the glasses.

After the PA briefs the surgeon on the situation, he asks if the surgeon agrees with the assessment and then begins the procedure.

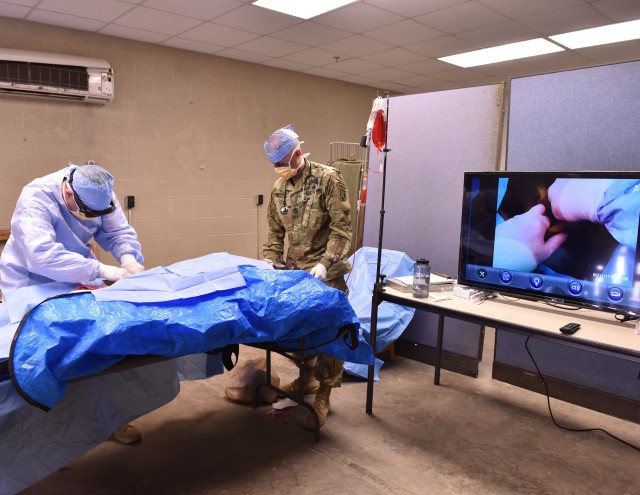

The surgeon is not only able to communicate and provide feedback to the PA throughout the procedure, but he is also able to help monitor vital signs and is able to draw or write directly within the PA's field of vision. This allows the PA to immediately identify incision points or problem areas as the surgeon's notes "appear" on the patient.

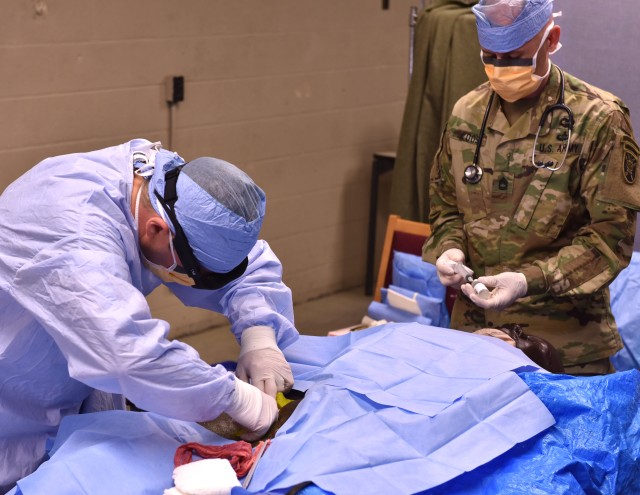

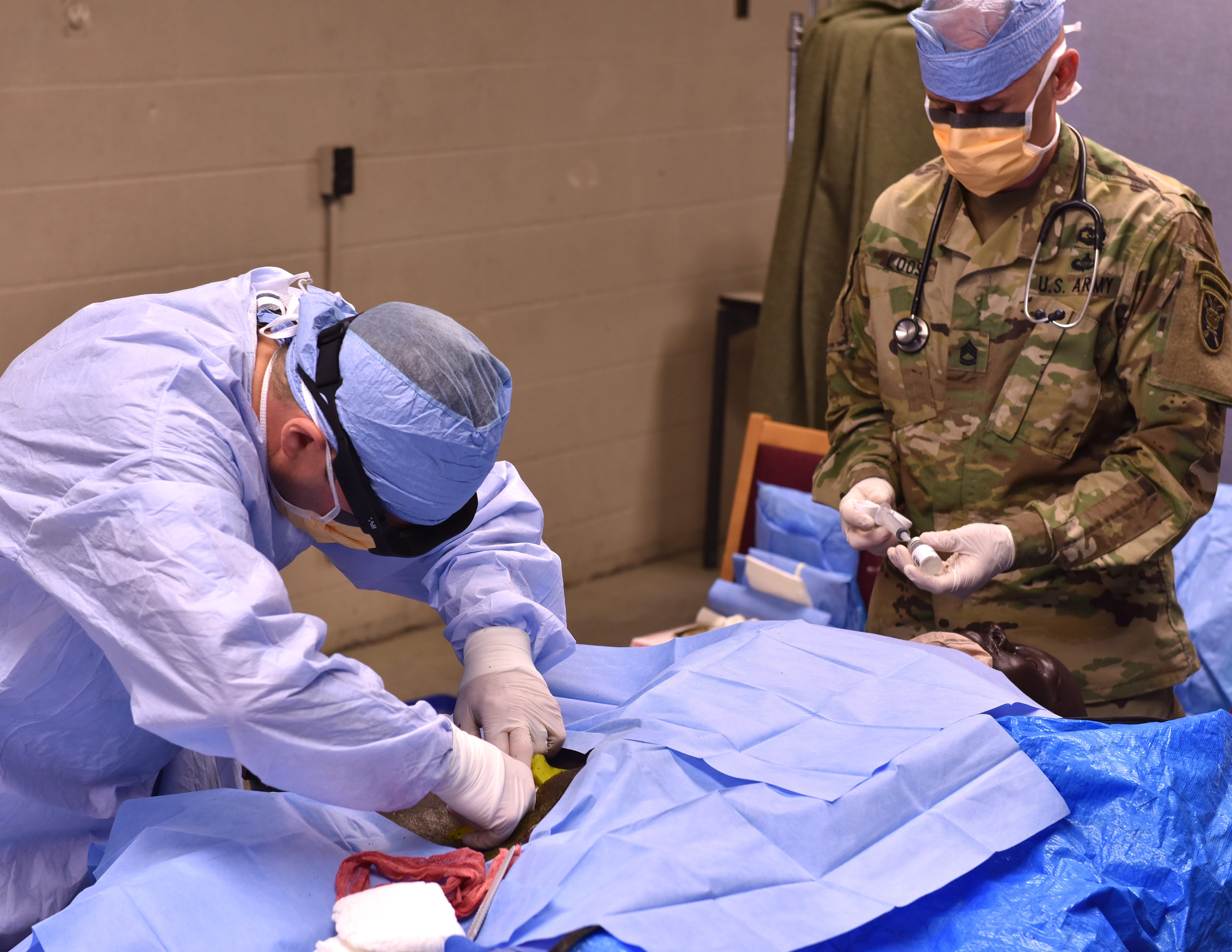

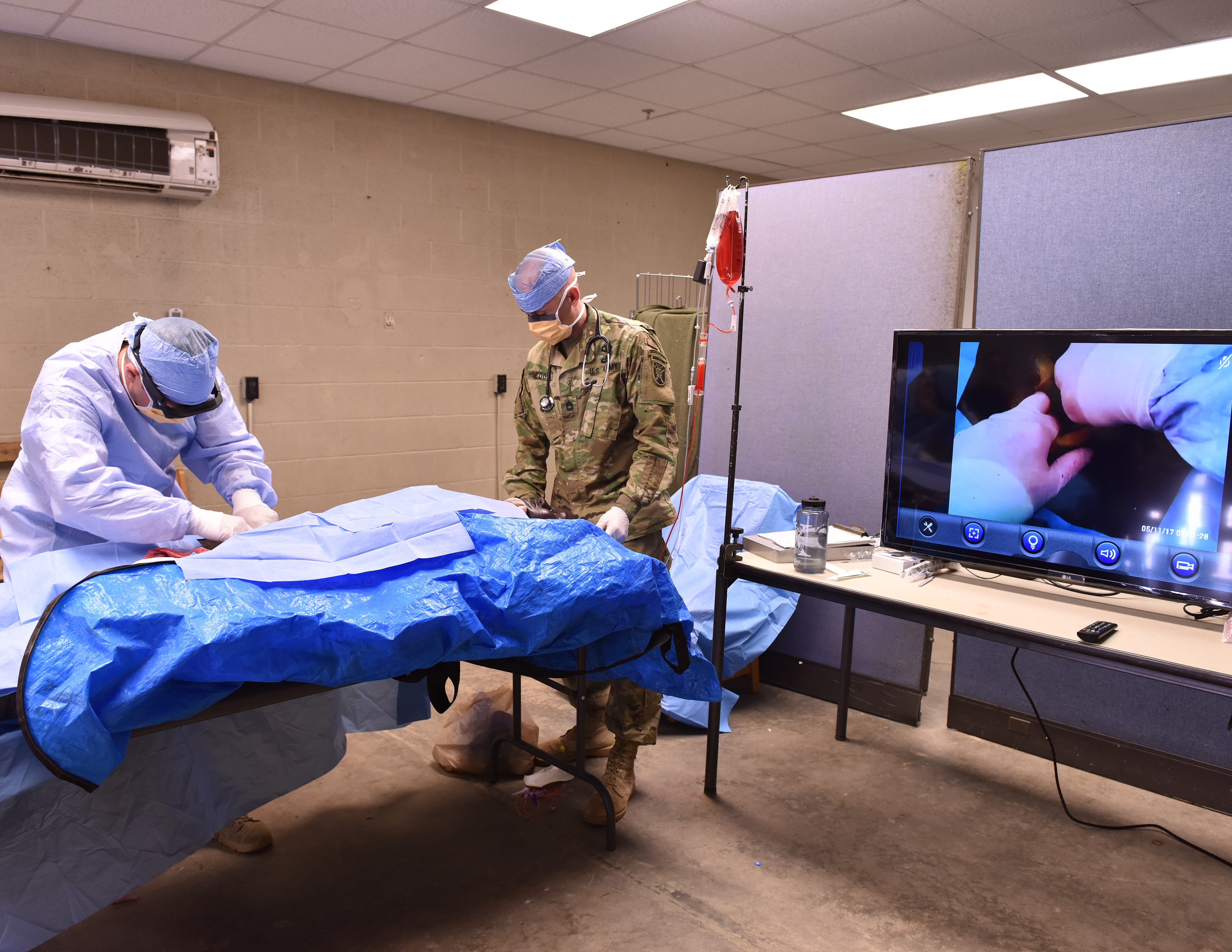

This scenario was the basis for training recently conducted at Fort Bragg's Medical Simulation Training Center. Based on a real life injury that caused the death of a Soldier in Somalia, the training helped explore a way that physician assistants can step in to perform lifesaving measures on a Soldier injured in theater where there either isn't the time or the capability to get them to a surgeon immediately.

The training also tested a new capability that will allow forward providers to stabilize injuries that threaten life, limb, or eyesight. This capability comes in the form of the augmented reality glasses that the PA wore, which not only gave him the ability to review the procedure before he performed it, but also allowed the surgeon to be there with him even though the surgeon wasn't physically present.

"I've been in situations where this definitely would have been helpful," said Navy Lt. Cmdr. C. Long, the Special Operations Forces physician assistant who performed the procedure during the training scenario. "When it's a situation where it's literally life or death, I'd rather be able to do something to try to save their life rather than nothing and just sitting there and watching them die."

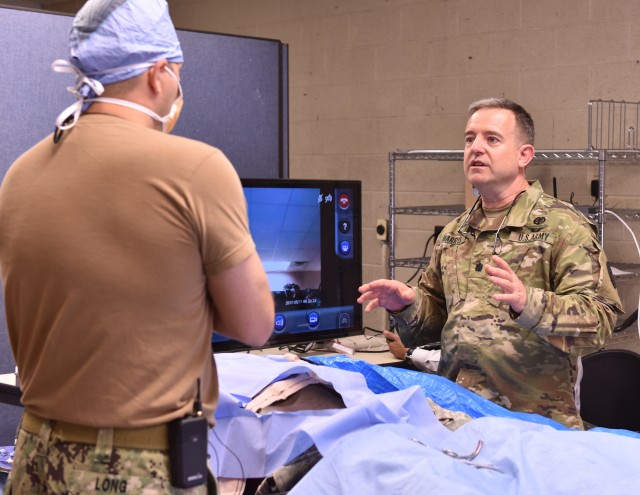

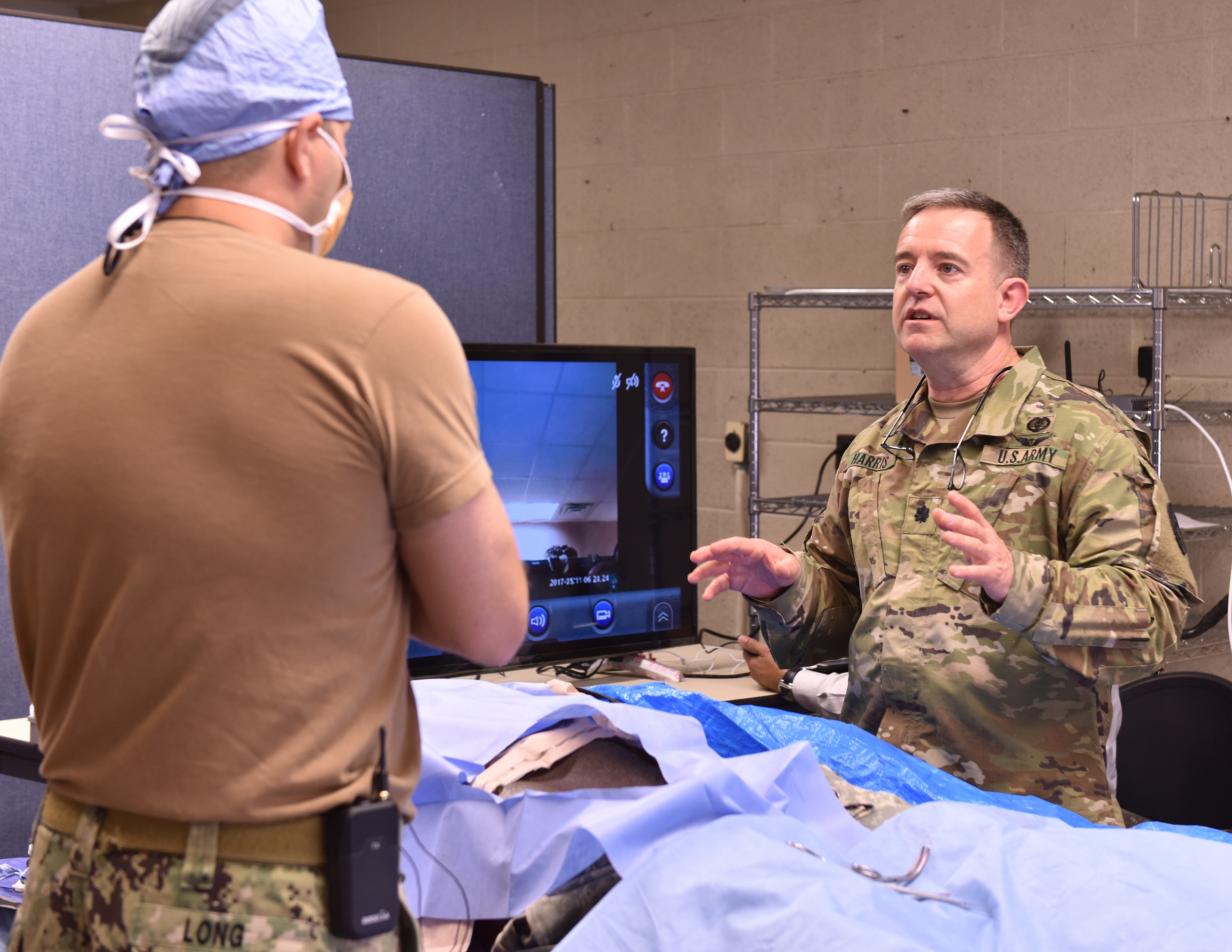

Dr. (Lt. Col.) Tyler Harris, an orthopedic surgeon at Womack Army Medical Center (WAMC), served as the surgeon and tele-mentor during the training. As Long wore the glasses and performed the procedure to stop the bleeding on the manikin, Harris was watching on a computer screen at another location. He was able to not only observe everything that Long was seeing and doing, but was also able to talk to him. Harris was even able to take a screen shot of Long's field of view, draw a line on it where the incision should go and send that image back to Long's glasses so that Long knew exactly where to cut when beginning the procedure.

Harris highlighted that he received the same training as the PA in the field so that he not only knows how the equipment works and how to use it, but he also knows the training the PA received on how to perform the procedure from beginning to end. He said that's the best way to ensure that everyone is on the same page, no matter who is on the other end of the phone from either side.

"From this training, I'm confident that we can guide a provider remotely to save a life," Harris said. "The procedure and the training are straightforward. With just two instruments and a pair of glasses, we saved a guy's life in under a minute."

Army Special Operations Forces are currently serving in more than 60 countries around the world. Most teams are too small and sometimes in too remote of a location to have their own organic surgical support, said Lt. Col. Stephen DeLellis, the Deputy Surgeon at U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC).

"We're not training folks to do surgery," said DeLellis, who is also a physician assistant. "Surgery is a surgeon's business. We're just giving them the ability to get our special operators to a surgeon. We're giving them the ability to stop a hemorrhage, to save limb, to sustain someone's life until we can get them to a care facility with a surgeon."

Eventually, the training program will expand to include guidance for non-surgical providers on providing advanced burn care, releasing pressure behind an eye, packing and temporarily closing the abdominal cavity, easing pressure in the skull and, as in the training scenario, accessing deep vessels to stop bleeding. The list was jointly developed by USASOC medical staff and Womack surgeons, all with the intent of what can realistically be done with the end goal of being able to immediately save someone's life, limb(s), or eyesight.

"The point is to teach these lifesaving procedures to the people who are actually out there providing care in the field," said Lt. Col. Kenneth Nelson, an orthopedic trauma surgeon at WAMC. "This is already being done with Special Operations medics already trained to do a number of these procedures. This isn't a time to be territorial, it's a time to come together to save lives. I can't bring someone back to life, but if someone in the field is able to stabilize them so they get to me alive and breathing, there's a lot I can do to fix them up then."

While the preference is always to have an experienced surgeon with a full surgical team close by to support all deployed forces, that's simply not feasible. Special Forces medical sergeants have been receiving training to perform anesthesia and minor surgical procedures since the Vietnam War. This training would expand on that to provide physician assistants and non-surgical physicians those same skills.

"We're not asking someone who has never touched a scalpel or handled tissue before to do this," said Harris. "Everyone who does this will be fully trained on the procedures before they're asked to provide treatment in the field. Non-surgeons do a variety of surgical procedures all the time. So do paramedics. This isn't all that far-fetched and with the technology that's available, it makes more sense than ever before to start training PAs to do this."

As part of the training, non-surgeons will not only be fully trained on the equipment and procedures, they will also be brought in to the operating room in a garrison environment to serve as surgical assistants to more fully understand the scope of their responsibilities.

In the end, the importance of bringing this technology and capability to military medicine comes down to saving lives.

"To save the lives of those who are putting themselves in harm's way to protect us, we simply need more surgically capable people," said DeLellis. "We just don't have enough to go around and when you're talking about some place like Africa where there's thousands of miles and dozens of borders between you and the surgeon, having this technology available and providers trained on how to use it can potentially save a life that might have previously been lost."

Social Sharing