WASHINGTON (Army News Service) -- When people think about the great Army generals of World War II, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall come to mind.

But when the historic military figures of World War I are remembered, one name always stands out: Gen. John J. Pershing.

Pershing is venerated because his achievements in WWI compare favorably to those of all the top WWII generals combined, according to Eric B. Setzekorn, a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History, who authored a just-released pamphlet available free online titled, "Joining the Great War: April 1917 to April 1918." About 10,000 copies of the pamphlet have been printed. It can be viewed online at http://history.army.mil/html/books/077/77-3/index.html.

Although Pershing shines for his leadership and achievements, it took the contributions of many other exceptional leaders to support the greatest-ever build up to war, of course, and Setzekorn chronicled their accomplishments in the pamphlet as well.

When Congress declared war on Germany, April 6, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker turned to Pershing, Setzekorn said. "It's an amazing degree of trust given to him by Wilson and Baker to really go over to France and make this work, with him calling the tune on nearly everything."

Why was Pershing such a central figure in the war?

Early in his career, Pershing cut his teeth on the Western frontier, participating in the Indian wars. Later, he participated in the Spanish-American War, serving with the 10th Cavalry, the famed "Buffalo Soldiers," fighting alongside Col. Theodore Roosevelt's "Rough Riders" in Cuba.

About two years later he was in the jungles of the Philippines, fighting guerilla insurgents. Just before World War I, he led the U.S. Army's expedition into Mexico to stem the flow of bandits across the Southwest border. To sum up, Setzekorn said, "he was the only figure with a lot of command experience."

But to fight and win a war requires organization, training, logistics and diplomacy, in addition to actual fighting, he added.

ORGANIZATION

When the U.S. declared war, only about 133,000 Soldiers were on active duty and some National Guard Soldiers were on the Southwest border, Setzekorn said. By the time the war ended Nov. 11, 1918, the Army was 4.2 million men strong.

In order to get those numbers in the shortest amount of time, Congress and the administration decided to enact a draft on May 18, 1917, rather than rely on an all-volunteer force.

A large-scale draft during the Civil War had resulted in widespread riots, particularly in New York and Baltimore, Setzekorn said. So Baker worked closely with Congress to avoid that kind of social unrest by developing a conscription policy that relied more on local authorities than on federal agencies in administering the draft.

The Guard, which was federalized, figured prominently in WWI, Setzekorn said, with two of the first four divisions going to war in late 1917 consisting of Guard Soldiers.

But the Reserve didn't play much of a role in the war, he added. Civilians experienced in logistics, medicine and engineering were quickly recruited to fill those critical slots as a contracted workforce. One of the lessons of the war, Setzekorn said, was the need for an expanded Reserve.

TRAINING & EQUIPPING

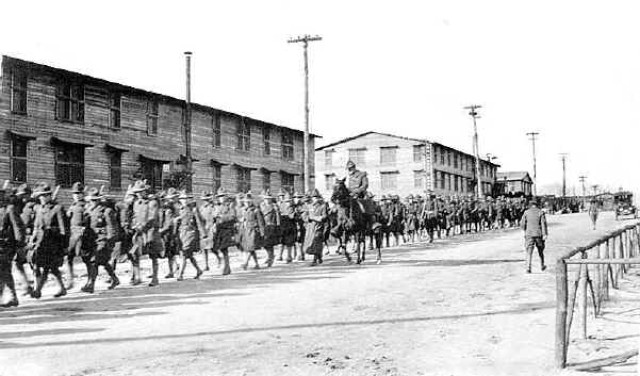

The next problem was establishing training and mobilization sites. Thirty-two hastily-built or expanded training camps were established across the U.S., including Camp Meade, Maryland; Camp Humphries, Virginia (which later became Fort Belvoir); Camp Fremont, California; Camp Travis, Texas; Camp Merritt, New Jersey and Camp Grant, Illinois. Camp Merritt, Setzekorn said, became the largest embarkation facility.

Each camp was designed to train 40,000 Soldiers at a time; in essence, they were like small cities that sprang up nearly overnight.

At first, Soldiers didn't have enough rifles so they trained with sticks. Those who did have rifles had the Springfield, a very accurate weapon, but one that was complicated to manufacture. To crank out millions of rifles quickly, the Army turned to the Enfield, a much simpler weapon to manufacture. It became the primary weapon used by Soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces, or AEF, as it was known.

As for finding adequately trained leaders, Setzekorn said, the Army at the turn of the century had shown foresight in setting up excellent leader-development courses, not just at the traditional U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, but also at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and at the Army War College.

The company- and field-grade officers who graduated "brought fresh ideas and a professional ethic to their duties," Setzekorn noted. Many of these men would be leaders in the AEF and provide top-level leadership for World War II as well.

Pershing also did a wonderful job in seeking French and British veteran officers to train U.S. Soldiers both at the camps in the U.S. and in training areas in France, Setzekorn said.

These young American officers' responsibilities grew exponentially. At the start of the war, a second lieutenant might be armed with a saber and pistol on a horse commanding a cavalry unit. A year later, that same officer might be commanding a battalion with duties that ranged from coordinating with air reconnaissance and artillery over a field phone to managing mechanized assets such as trucks and sometimes tanks.

"The level of complexity was so far beyond what anyone had ever experienced, and the technology was all new and frightening," Setzekorn said. "It was war on an industrial scale, the likes of which had never been seen before."

DIPLOMACY

When Pershing arrived in France June 10, 1917, he found his French and British allies desperate for manpower, Setzekorn said. Years of trench warfare had taken a toll. Millions of French and British forces had been killed or wounded, more in fact than all U.S. Soldiers killed or wounded in U.S. history.

Understandably, morale was wavering, and at one point, half the French army had mutinied. On top of that, Russia was weakening, and German troops on the eastern front were pouring westward, threatening to overrun allied lines, Setzekorn said.

The French and British had the notion that, "if you can give us these young, healthy, energetic Soldiers, we can train them and get our officers to lead them and that's the best way to fight Germany," he said.

"For political reasons, it was difficult for Americans to fight under a foreign flag, and Pershing had to navigate this problem diplomatically because you wanted to have an American flag and an American identity," Setzekorn said.

In essence, "Pershing was working to thread the needle by offering support, but at the same time never allowing American troops to come under control of France or Britain," he explained. "It was a tough issue that continued throughout the war, particularly in the spring of 1918 when France and Britain were becoming exasperated that it was taking so long for American Soldiers to become trained."

Setzekorn noted some exceptions to this control issue, known formally as the "amalgamation debates." African-American Soldiers of the 92nd and 93rd Divisions were incorporated into some French units and went on to fight with distinction.

The French and British were becoming exasperated with the issue of control and the perceived slow pace of the American buildup, Setzekorn said.

"A lot of people said, 'Americans, maybe this is just too hard for you,' but Pershing stood his ground saying we're going to get our divisions trained and our corps trained, and we're going to be the equals of France and Great Britain," he said.

Pershing succeeded "through his force of will," Setzekorn said. "He was a very strong character, cast in a very difficult role. I can't think of anyone who's even come close to that since then, certainly not during World War II or later wars. He was really it. Once you left U.S. soil it was Pershing calling the shots on almost everything."

CONCLUSION

The first year of WWI may not seem as exciting as its later years, at least in terms of battles fought, but that period "provided a foundation for the U.S. to be a major player both in the war and ... the emergence of the U.S. as a force in the world," Setzekorn said.

Marshall, Patton, Eisenhower and other young officers under Pershing's command saw what it took to build an Army, he said, "not the flashy stuff on the battlefield but the grunt work of training and logistics, developing doctrine and educating key leaders."

That education would pay big dividends when these men led their own armies during WWII, he continued.

April 1917 to April 1918 "is really the birth of the U.S. Army as we know it," Setzekorn concluded. By April 1918, the doughboys, as Soldiers were called, became the Army that exists today with divisions, combined arms, a tank corps, an air service, a chemical warfare service and so on.

-----

(Editor's note: Although there were some battles in which Americans participated during the pamphlet's timeframe, such as Cambrai in November and December 1917, CMH plans to document those in subsequent pamphlets, 10 of which are planned.)

Follow David Vergun on Twitter: @vergunARNEWS)

Related Links:

Joining the Great War, April 1912-April 1918

U.S. Army Center of Military History Publications Catalog for ordering pamphlets

Social Sharing